This proposal tells a story about a return. A return to culture and tradition. A return to healthy water and land. It is about Returning to A’se’K. For the Pictou Landing First Nation in Nova Scotia, Canada, A’se’K, meaning “the other room” in Mi'kmaq, was a former tidal estuary in their backyard. It was the heart and provider for this Indigenous community — offering sustenance, medicine and facilitating recreation and ceremony. In 1967, this all changed with the arrival of a pulp mill which initiated over 50 years of pulp production, effluent pollution and prompted one of Canada’s worst cases of environmental racism. This proposal arrives at a timely mark in the story of A’se’K, with the closure of the mill in 2020 and remediation of the site just beginning. Returning to A’se’K offers a landscape strategy for the community to reclaim and re-engage in lost local knowledge and cultural practices associated with A’se’K through the restoration and monitoring of eelgrass and the protection, sustainable procurement and management of the American eel.

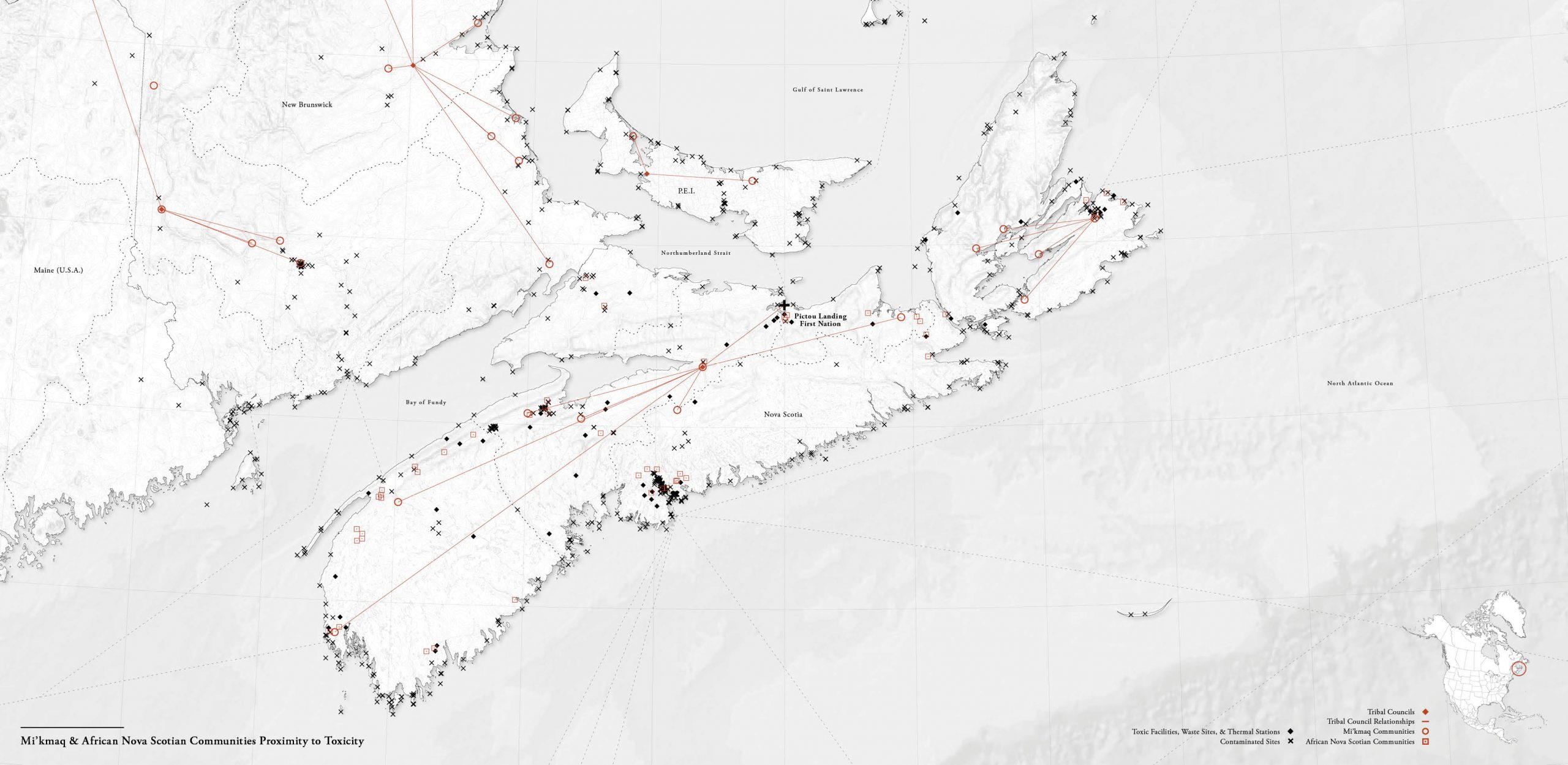

In Atlantic Canada, there are multiple cases of environmental racism. Pictou Landing First Nation, other Mi’kmaq bands and African Nova Scotian communities are disproportionately located near toxic facilities and sites.

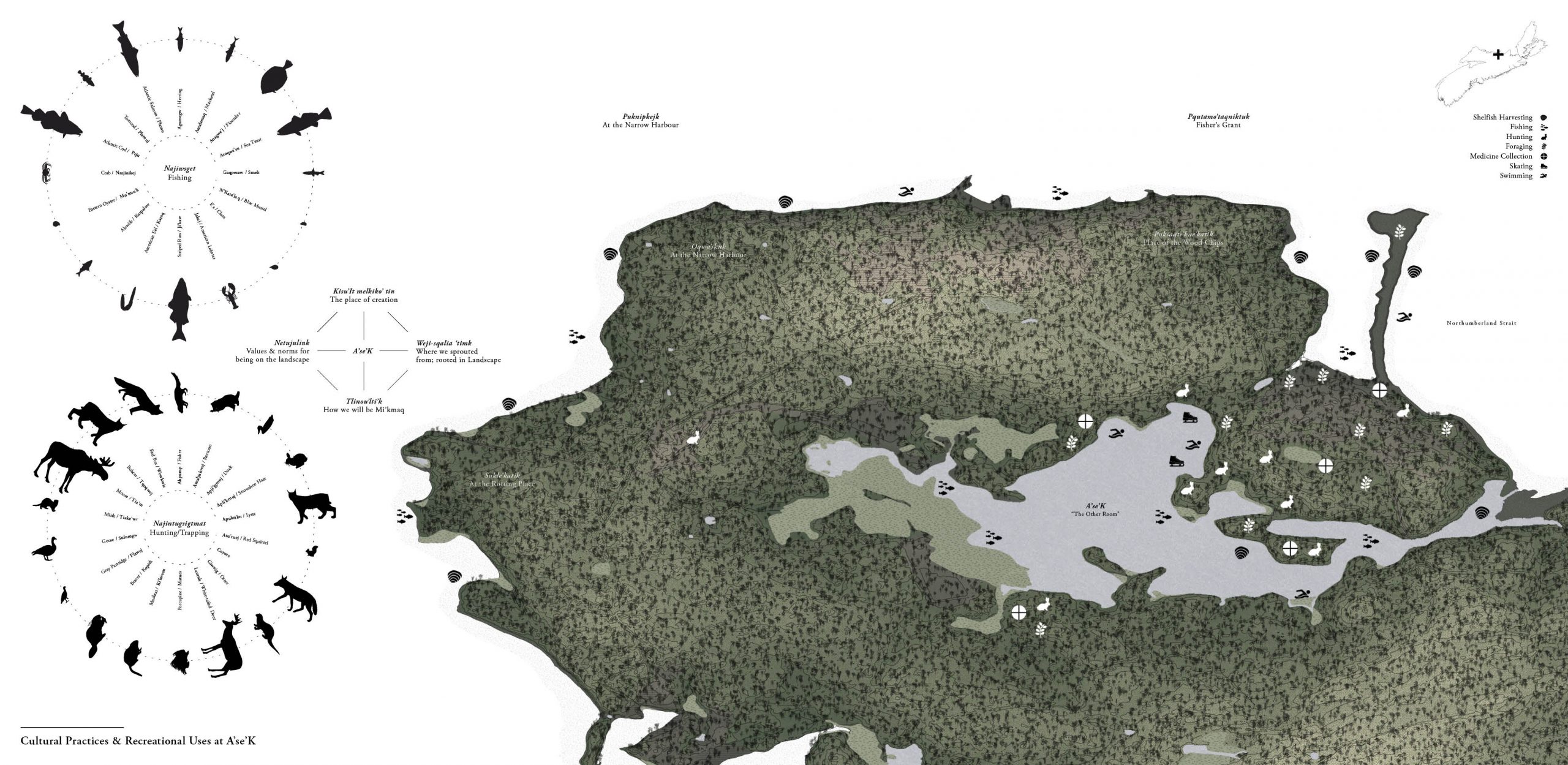

Before the mill, A’se’K supported Pictou Landing First Nation members' ability to live the ‘good life’, one that was healthy, thriving and sustaining. A’se’K was a flourishing ecosystem that provided sustenance and medicine and was used for recreation and ceremony.

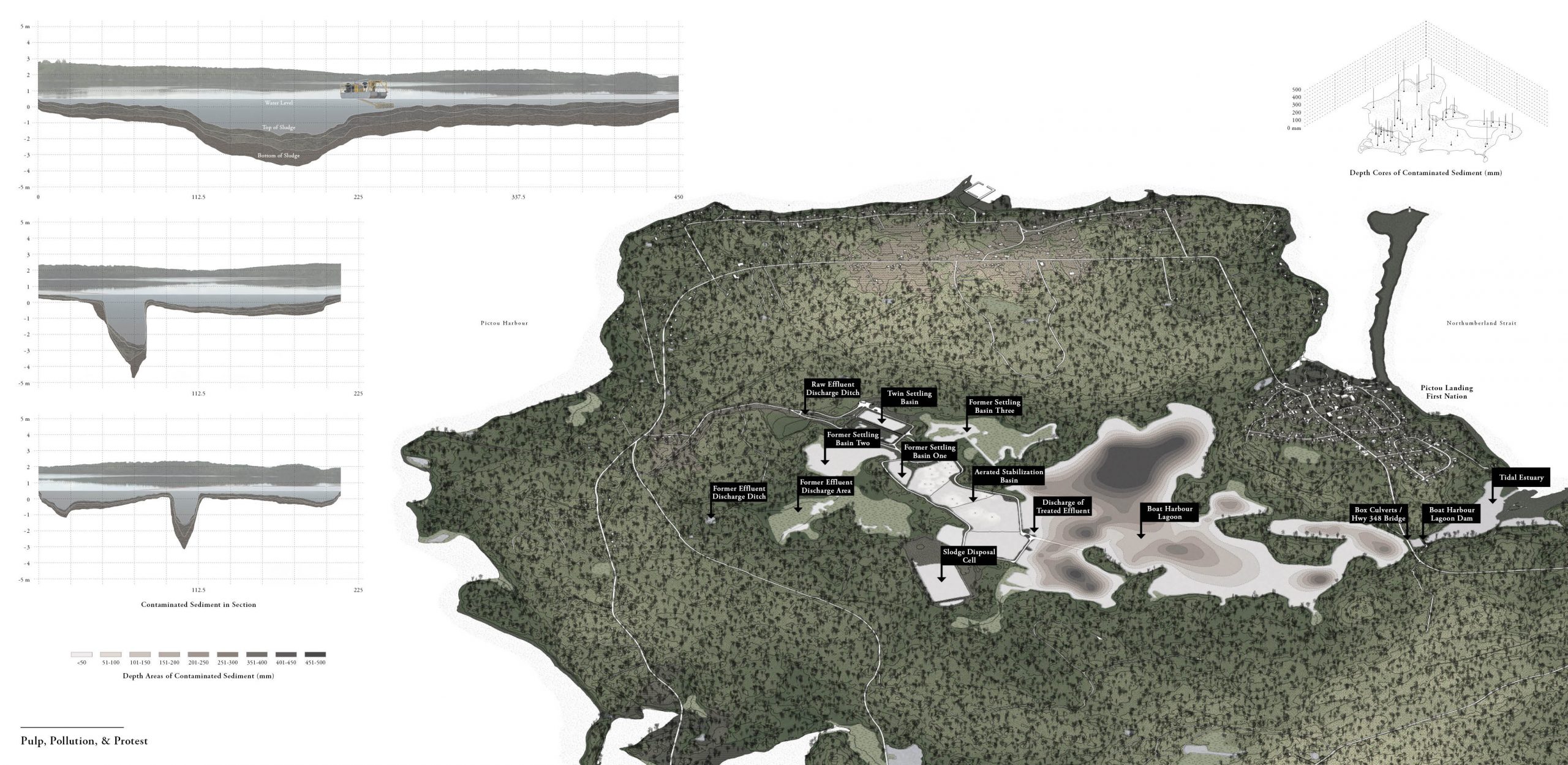

The ‘good life’ ended in 1967 when A’se’K was transformed and contaminated beyond recognition with raw effluent from a neighbouring pulp mill. The community endured daily dumping of 90 million liters of inorganic and organic pollutants for over 50 years.

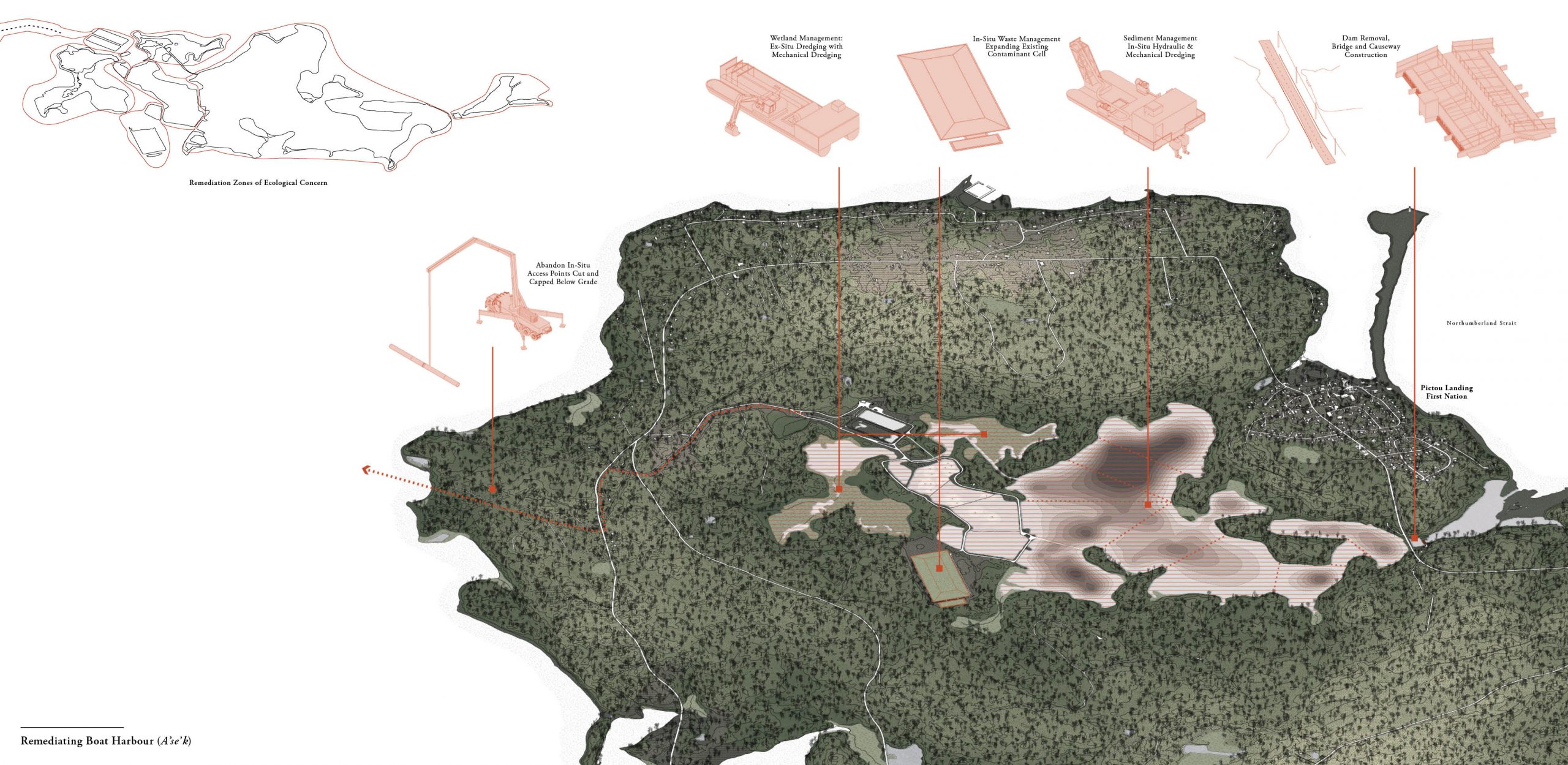

On January 31, 2020, the pulp mill’s operations shut down and dumping ceased. Shovels are now in the ground to remediate and restore Boat Harbour back to its pre-mill conditions to ultimately return the site back to the community.

The principle Mi'kmaq of Netukulimk guides the protection, sustainable procurement and management of eels as well as other creatures. Cultural practices like eel fishing have the potential to occur once again in the waters of A’se’K.

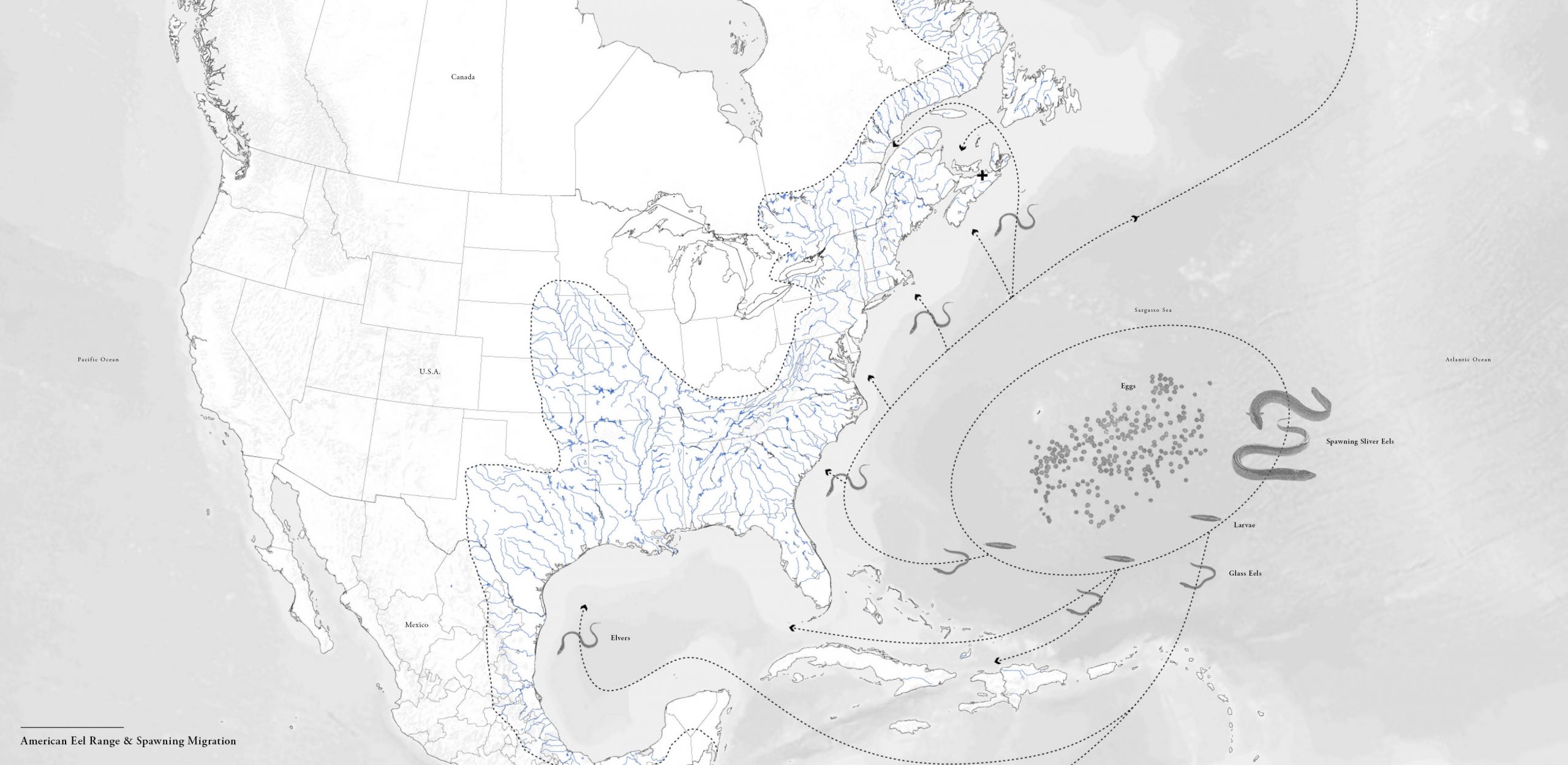

American eels spend most of their life in the same freshwater and estuary habitat connected to the Atlantic Ocean. When eels reach maturity after 15-25 years, they make an epic migration to the Sargasso Sea to spawn and then return.

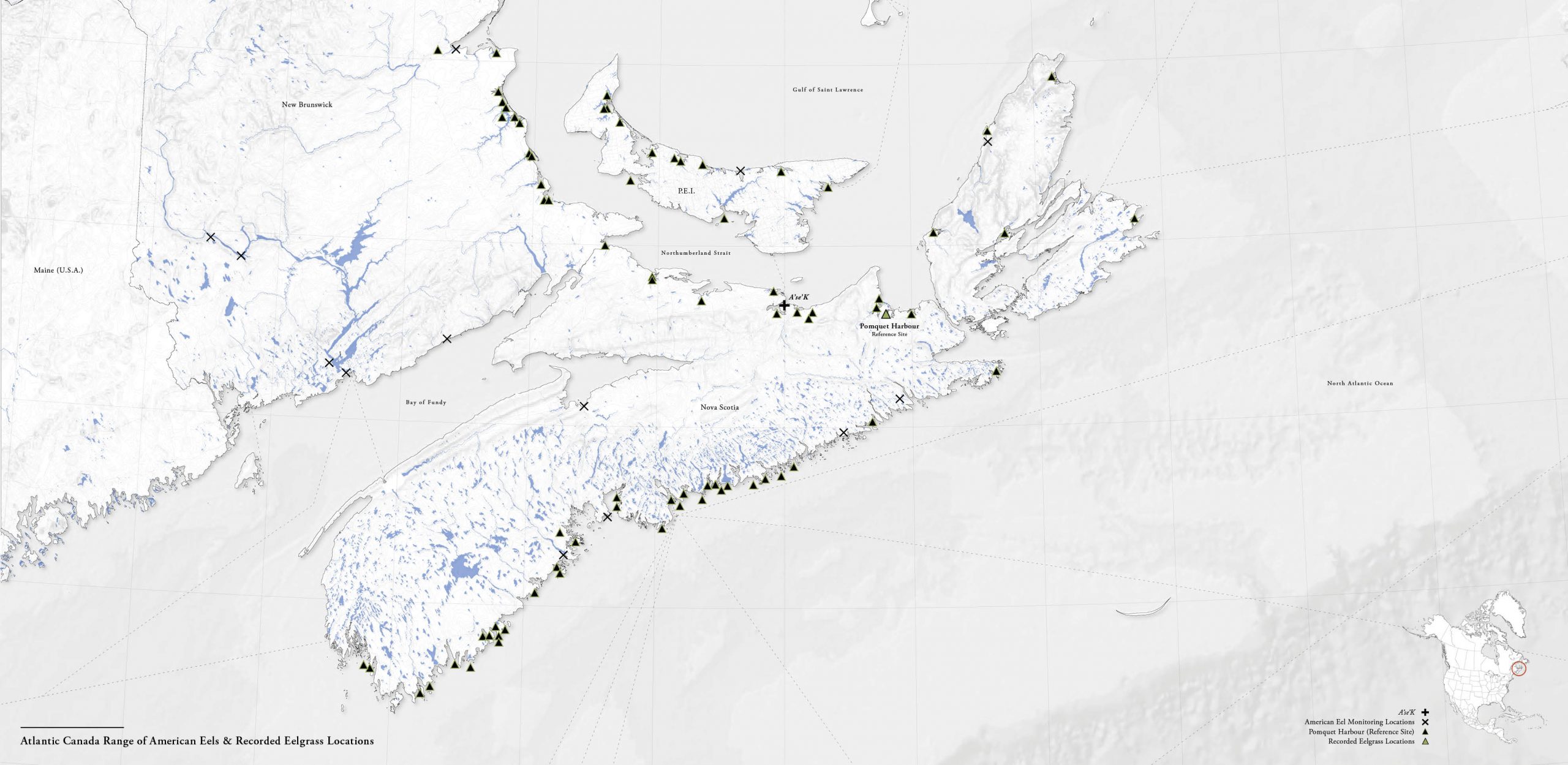

In Atlantic Canada, American eels are considered endangered. Commercial fishing has been closed in some areas to protect their numbers. However, for Mi'kmaq communities like Pictou Landing First Nation, eeling is a cultural right and is still practiced sustainably today.

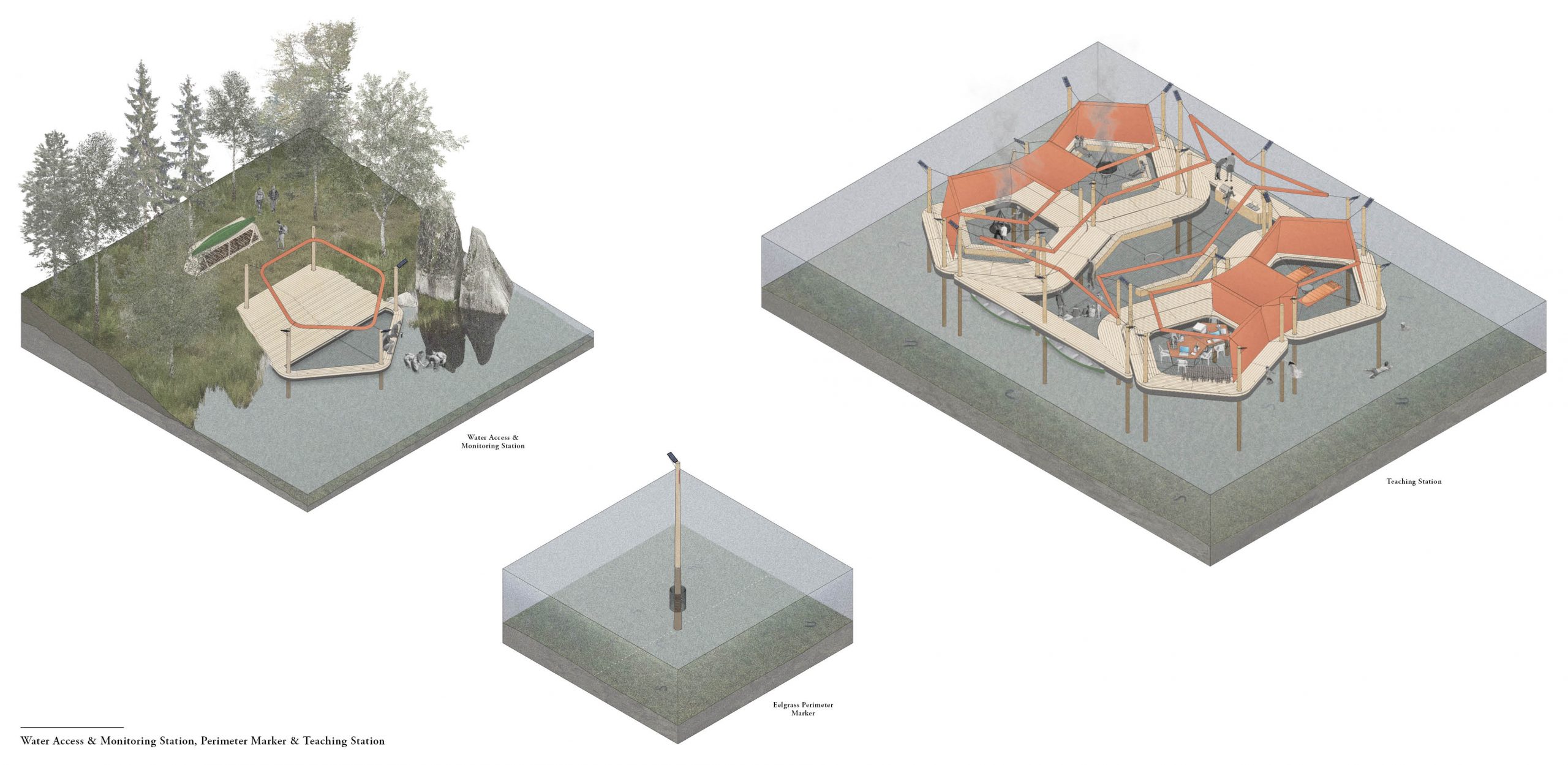

Eelgrass restoration occurs around the shallows of A’se’K integrated with eelgrass perimeter markers, eel stations, water access and monitoring stations as well as a central teaching station.

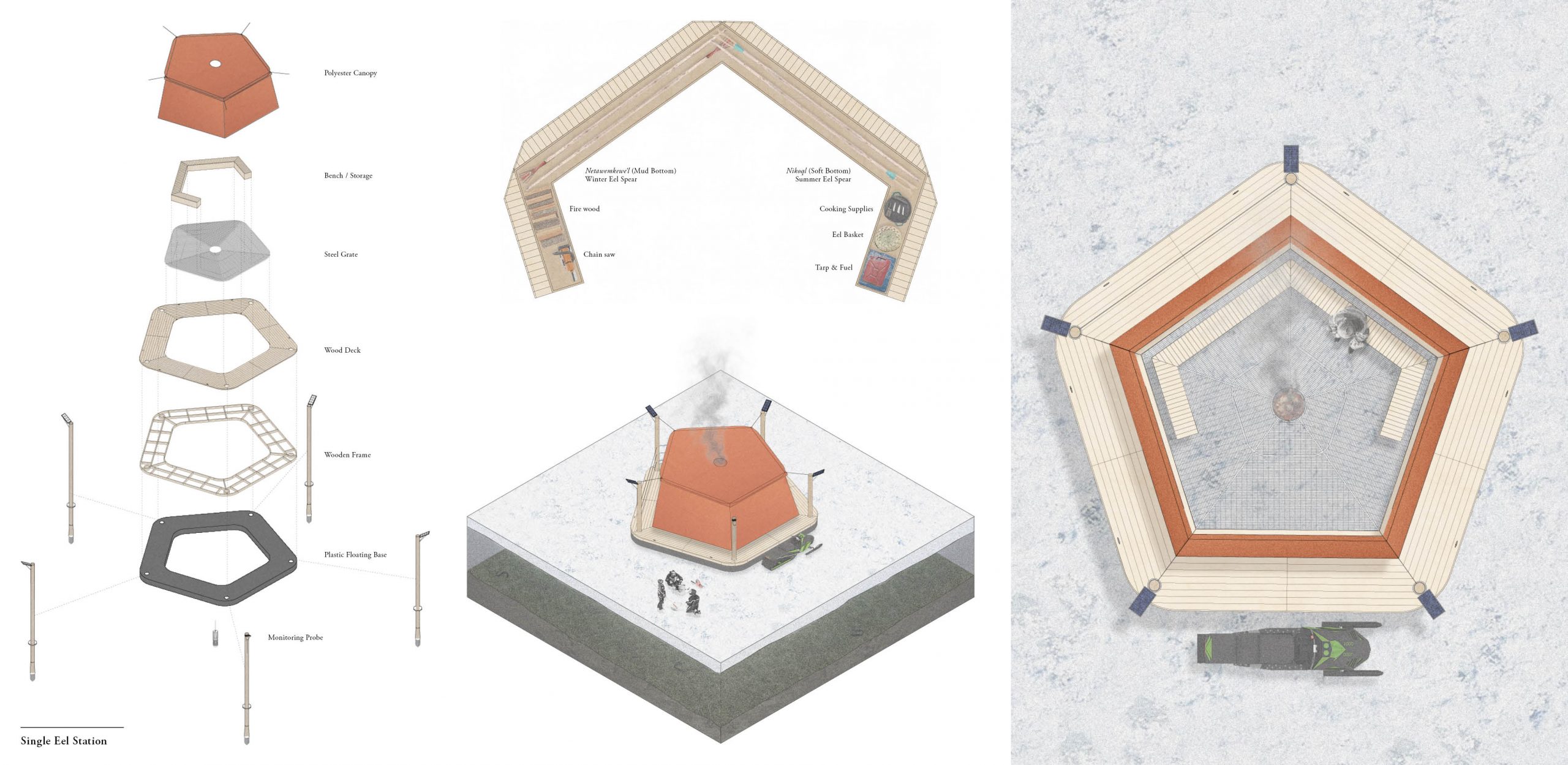

The floating single eel station accommodates gathering, cooking, eel fishing, tool storage, eelgrass and water quality monitoring, as well as summer and winter recreation. It comes equipped with a retractable polyester canopy with side coverings for year-round use.

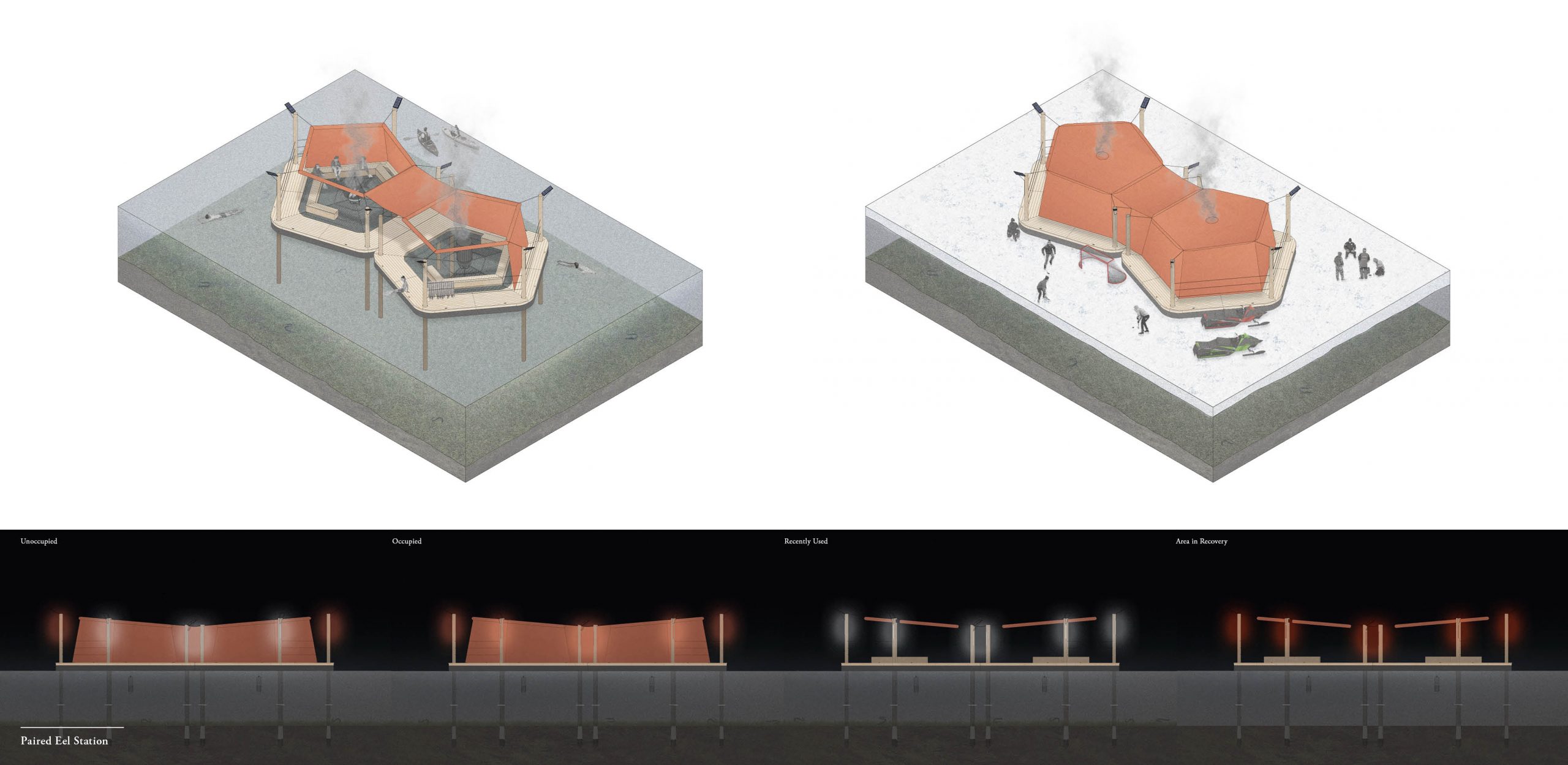

The paired eel station is a combination of two single eel stations. This configuration comfortably supports up to 10 people and can be adapted for further use.

Water access and monitoring stations provide essential ecological monitoring points. Perimeter markers indicate the outer boundary of the restoration area. The teaching station acts as an outdoor classroom for local youth to participate in land-based learning activities including eel fishing.

Returning to A’se’K offers a landscape strategy for the community to reclaim and re-engage in lost local knowledge and cultural practices associated with A’se’K.