Asbestos, Québec is home to the world's largest open-pit asbestos mine, which closed in 2012. The town challenges notions of the word "unhealthy," with people dying each year from asbestos-related diseases while living close to the massive pit that caused their trauma. To heal, Asbestos must move towards a healthy future. This project is part of a larger scheme to transform the town into one focused on researching and treating asbestos-related diseases, palliative care for patients, and environmental rehabilitation. By intrinsically integrating salutogenic and biophilic principles into the design, a symbiotic relationship between health and landscape forms.

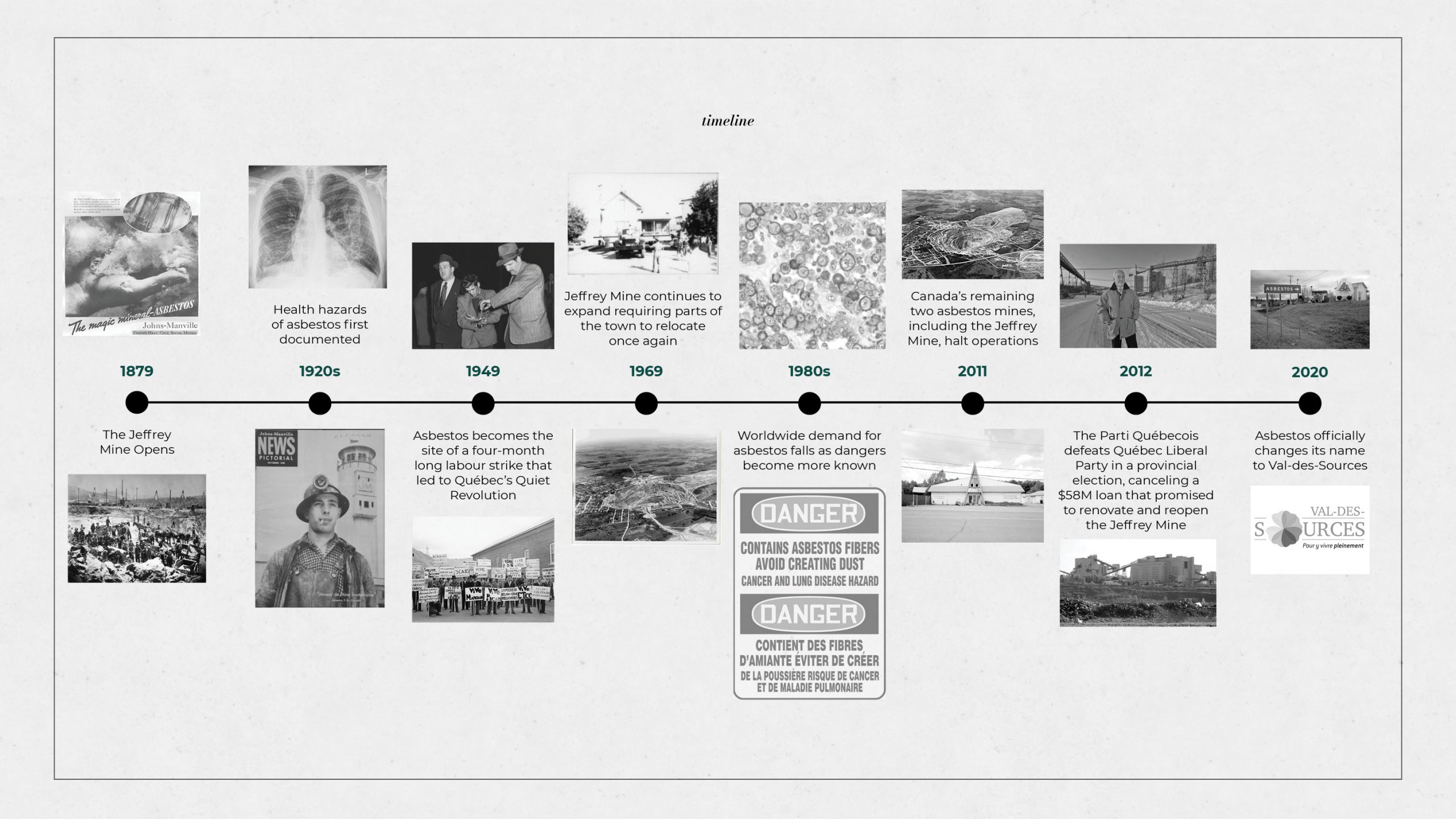

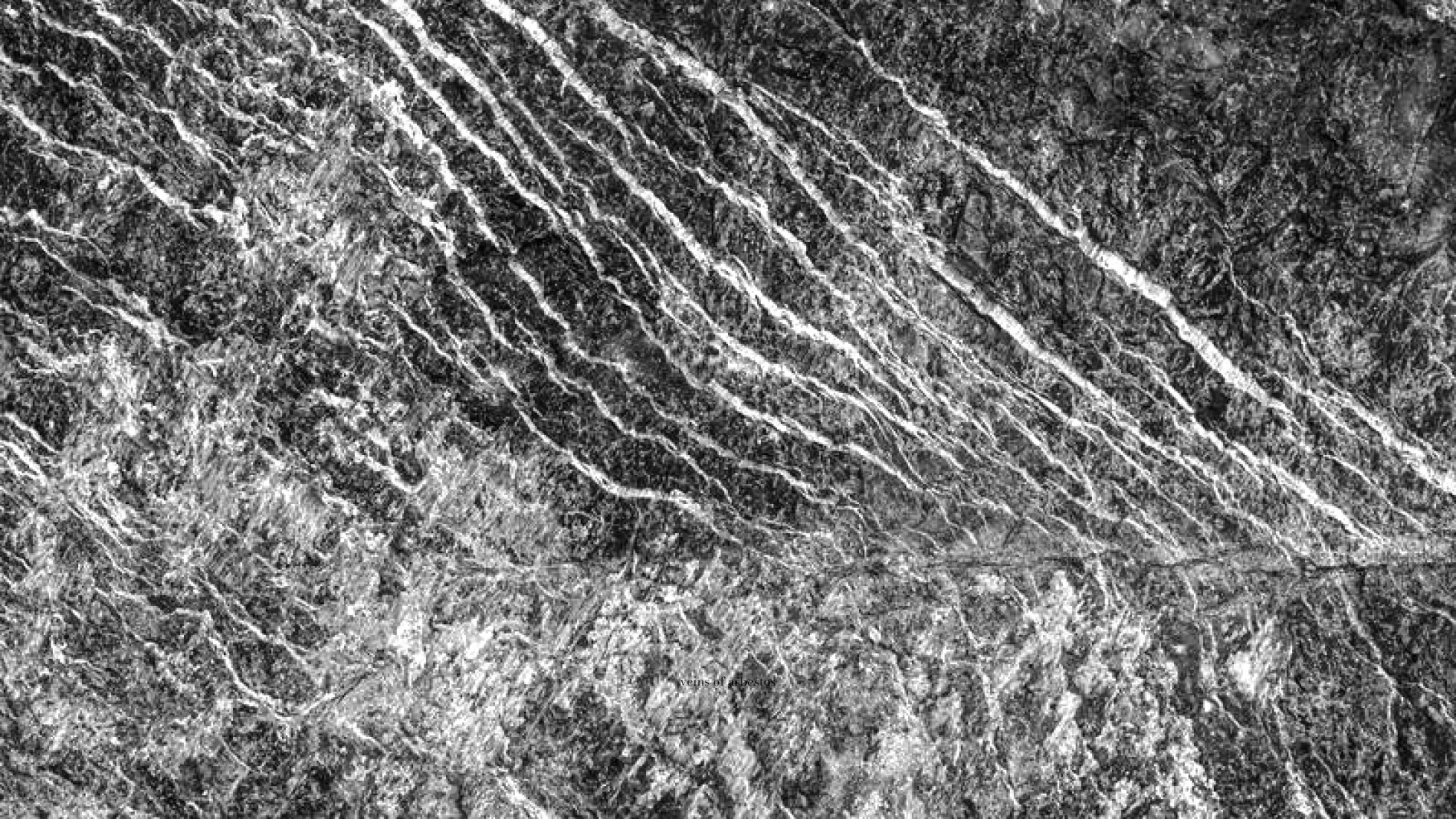

What is asbestos? We know asbestos as a mineral that used to be called the ‘magic mineral’ because of its flame-retardant properties. Today, we think of it as a hazardous material. Most people do not know that Asbestos is also an infamous small town in Québec. It is the epicenter of one of the deadliest health epidemics in Canadian history.

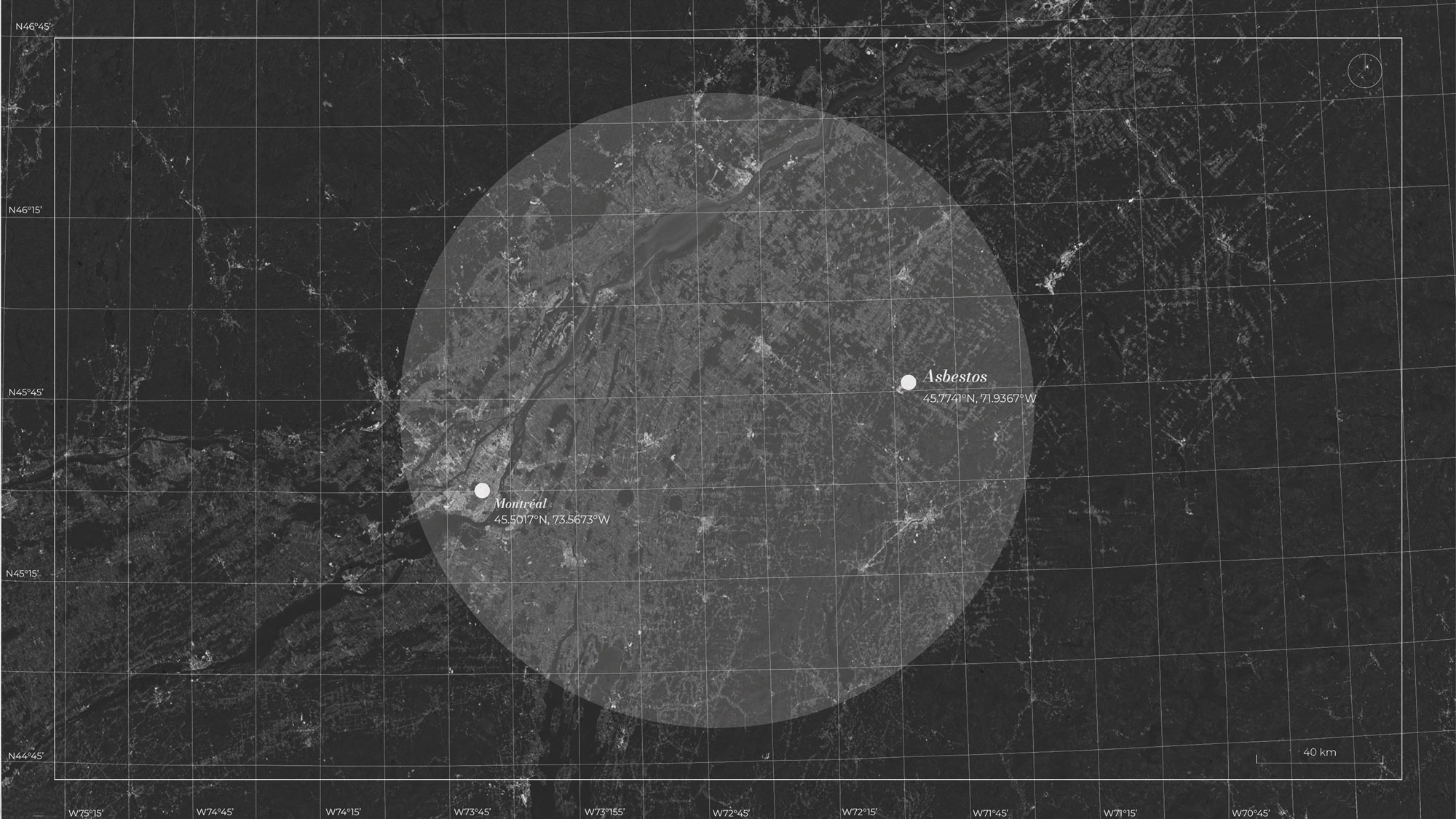

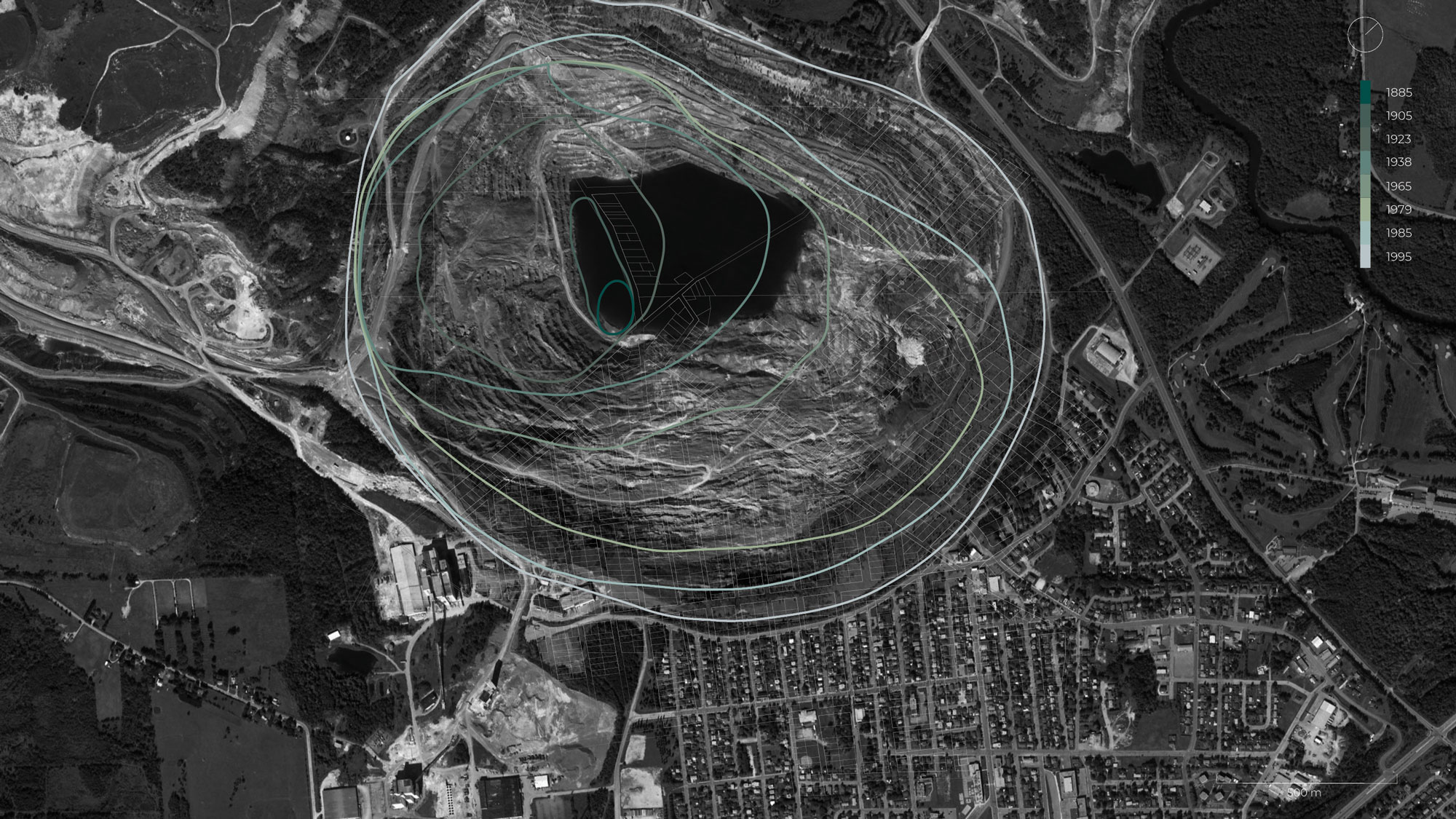

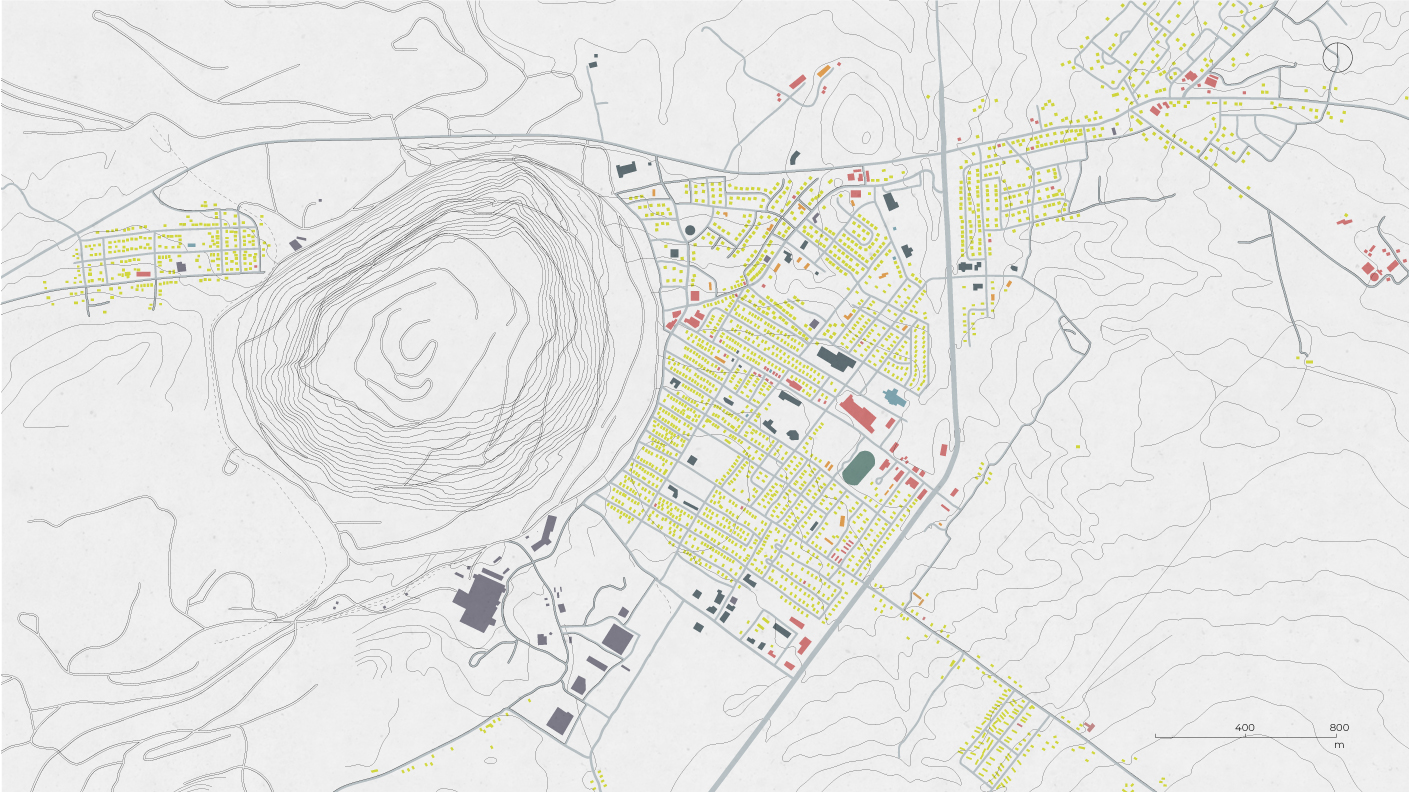

The town is located in the eastern townships of Quebec, just 2 hours east of Montreal. After chrysotile asbestos deposits were found in the area in 1879, asbestos mines were established. This resilient single-industry town subsequently grew around the Jeffrey Mine. It was owned and operated until 2012 by an American company called the Johns-Manville Company which mined, processed and manufactured asbestos goods. The town is now home to merely 5205, while at the peak of the industry in the 1970s the mine employed over 2000 people and the town had over 7000 residents. The Jeffrey Mine is the largest open pit asbestos mine in the world. Measuring 2 km in diameter, 370 m in depth, and 6 square km in total area. Asbestos, Quebec challenges our notions of the word unhealthy.

This is evident by looking at the past 124 years of the town’s history. It is unhealthy in an economic sense as the town was detrimentally affected by the closure of the mine causing job loss and mass migration. It is unhealthy in a social sense in that the conflict between English mine executives and French miners solidified with the health coverup and Quiet revolution. It is unhealthy in an architectural sense since many significant buildings were lost due to mine expansion. It is unhealthy in an environmental sense because the town still sits next to the mine and its colossal tailing piles. Most importantly, it is unhealthy in the sense that many people suffer from asbestos-related diseases that they were unknowingly exposed to through working at the Jeffrey Mine or simply living in the town. To heal, Asbestos must move forward towards a healthy future. Part of this was changing its name to Val-des-Source in December 2020 to mark this turning point.

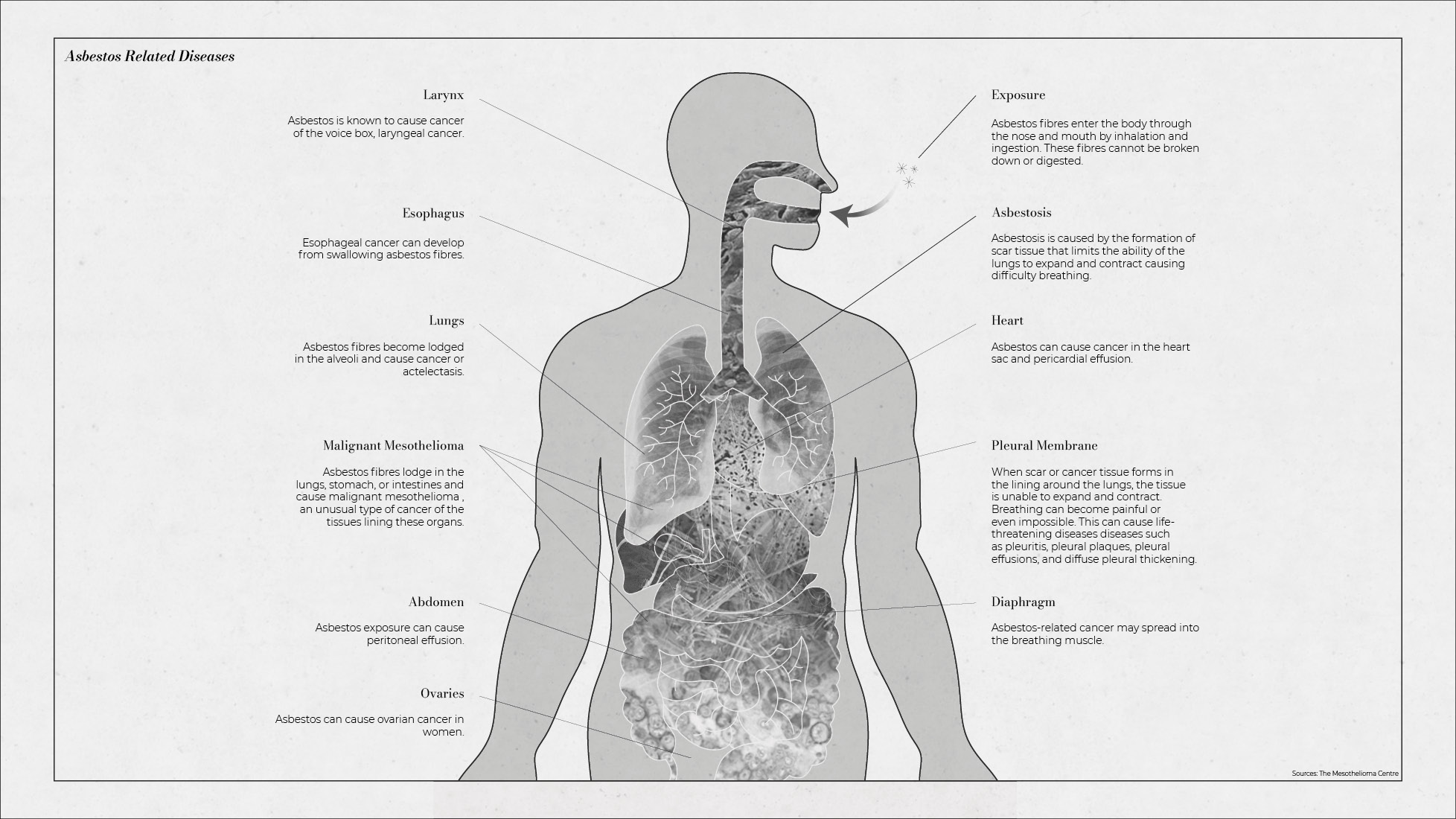

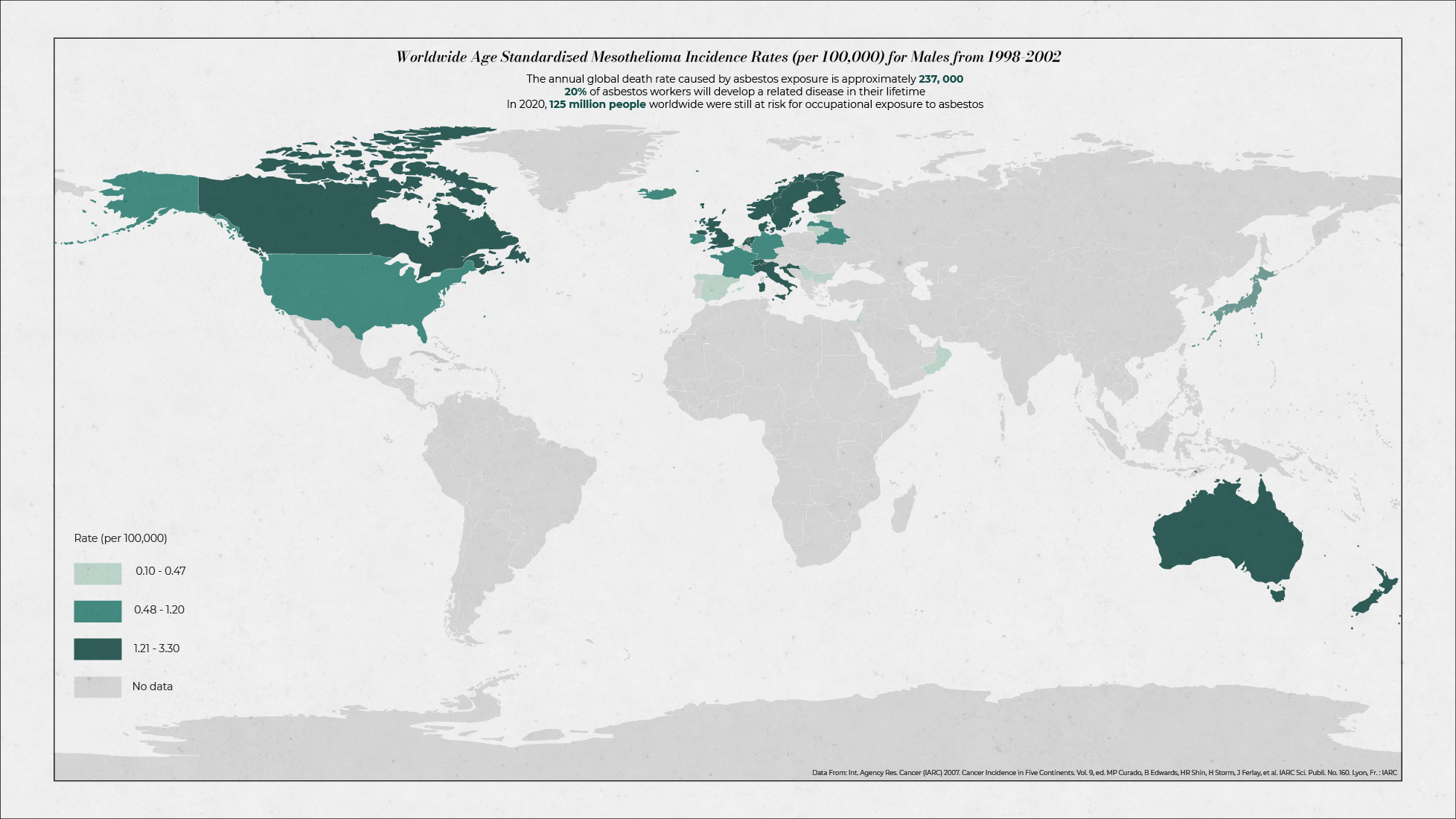

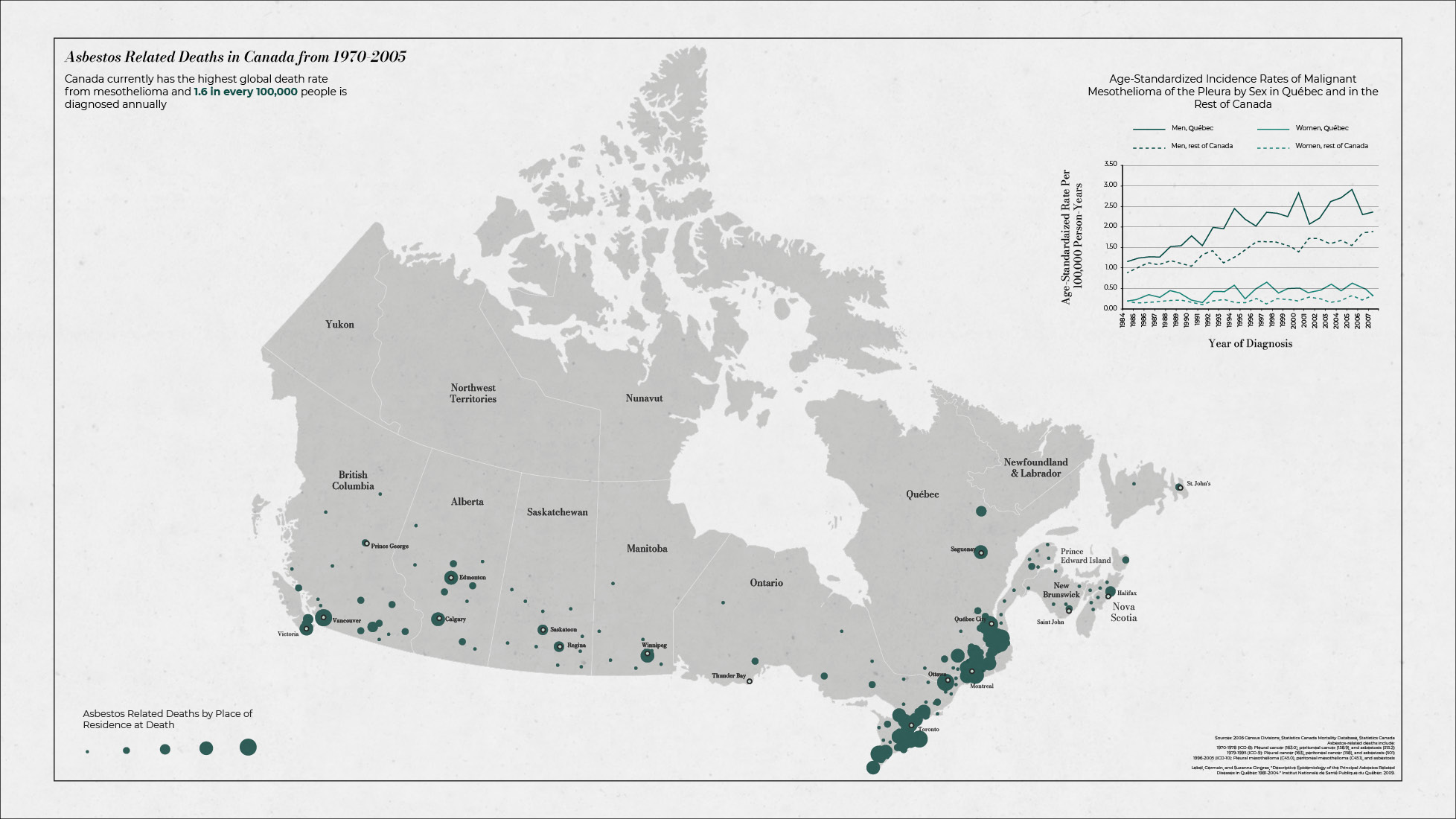

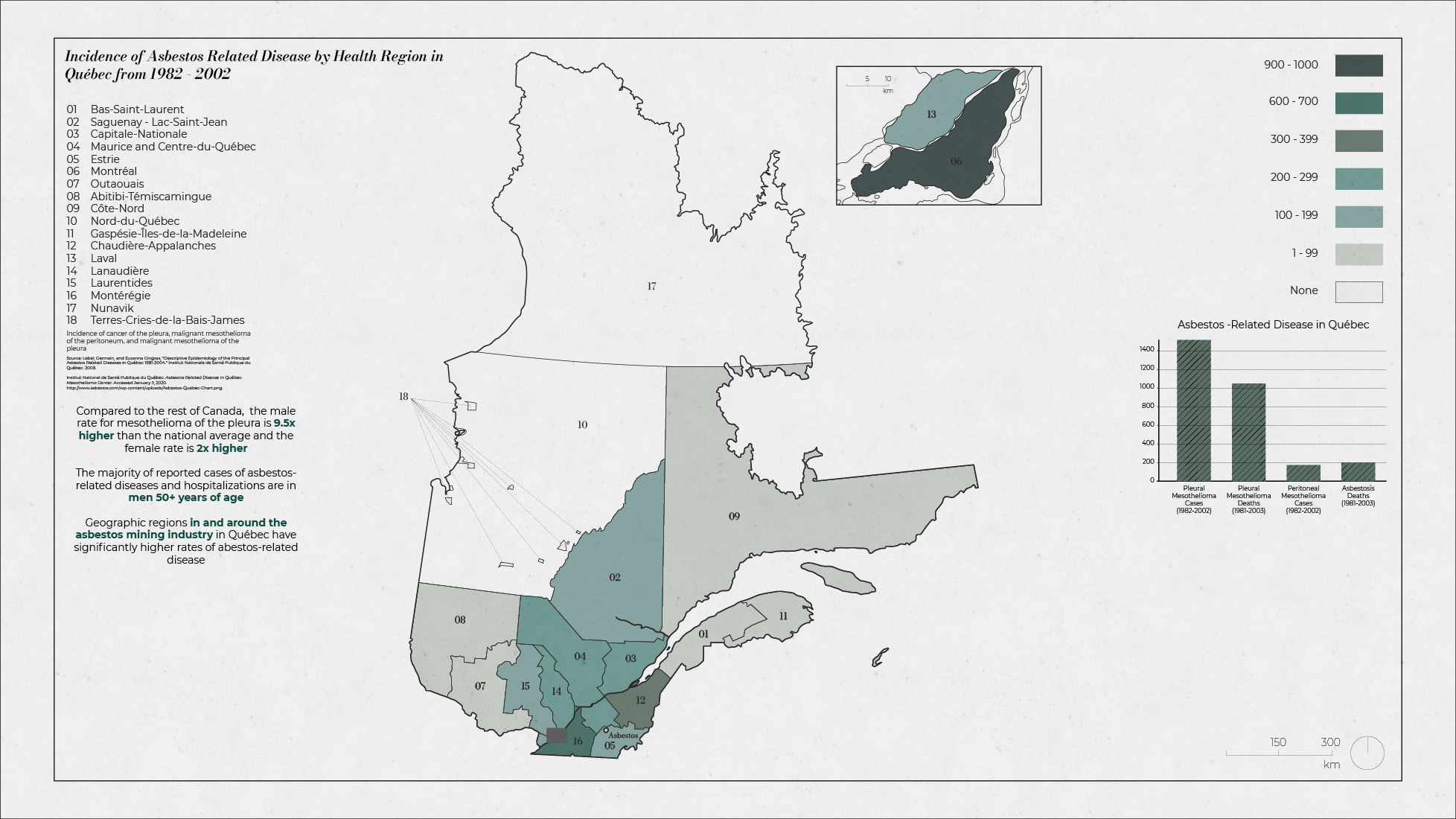

When looking at the mine and the surrounding area, one can understand this place as a dichotomy. A wasteland that sickened its people or a profound cultural landscape that brought prosperity to its people. This dichotomy is evident in the way in which the town perceives itself and the people who live there. The truth is that asbestos exposure is directly related to various cancers such as mesothelioma. It also causes life-threatening diseases such as asbestosis. On an international level, Canada’s incidence rate of mesothelioma is one of the highest in the world. Canada currently has the highest global death rate for mesothelioma. These rates are the highest in Quebec, specifically for men. Asbestos is located in the health region of Estrie. Geographic regions in and around the asbestos mining industry have significantly higher rates of asbestos-related disease.

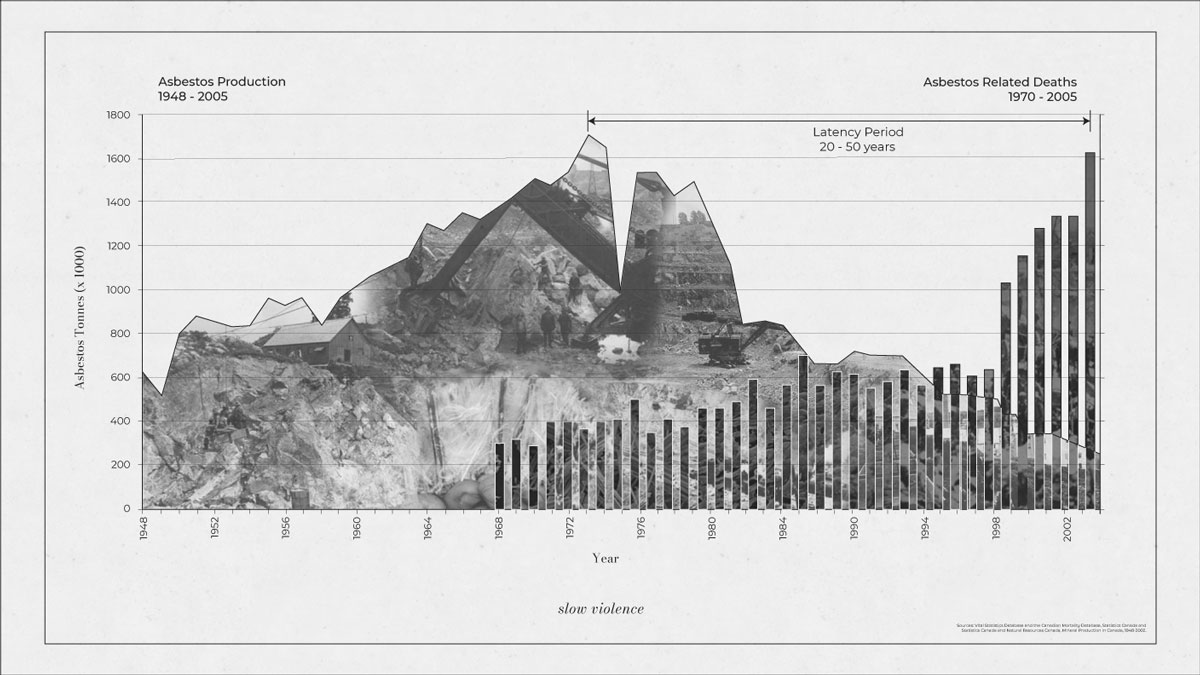

Asbestos inflicts slow violence on its victims meaning the latency period between exposure and disease can be between 20 and 50 years. This latency period for asbestos-related diseases provided the time-frame for the asbestos fibers to inflict slow violence against the miners, factory workers, and general population of the town who were all unaware of asbestos’ harmful effects. The peak of industry was in the 70s and we only began to see the rise in cases from this period in the 90s because of the latency period. Since the mine only closed in 2012, new cases caused by occupational exposure from the Jeffrey Mine will continue to be diagnosed up until 2062 and beyond.

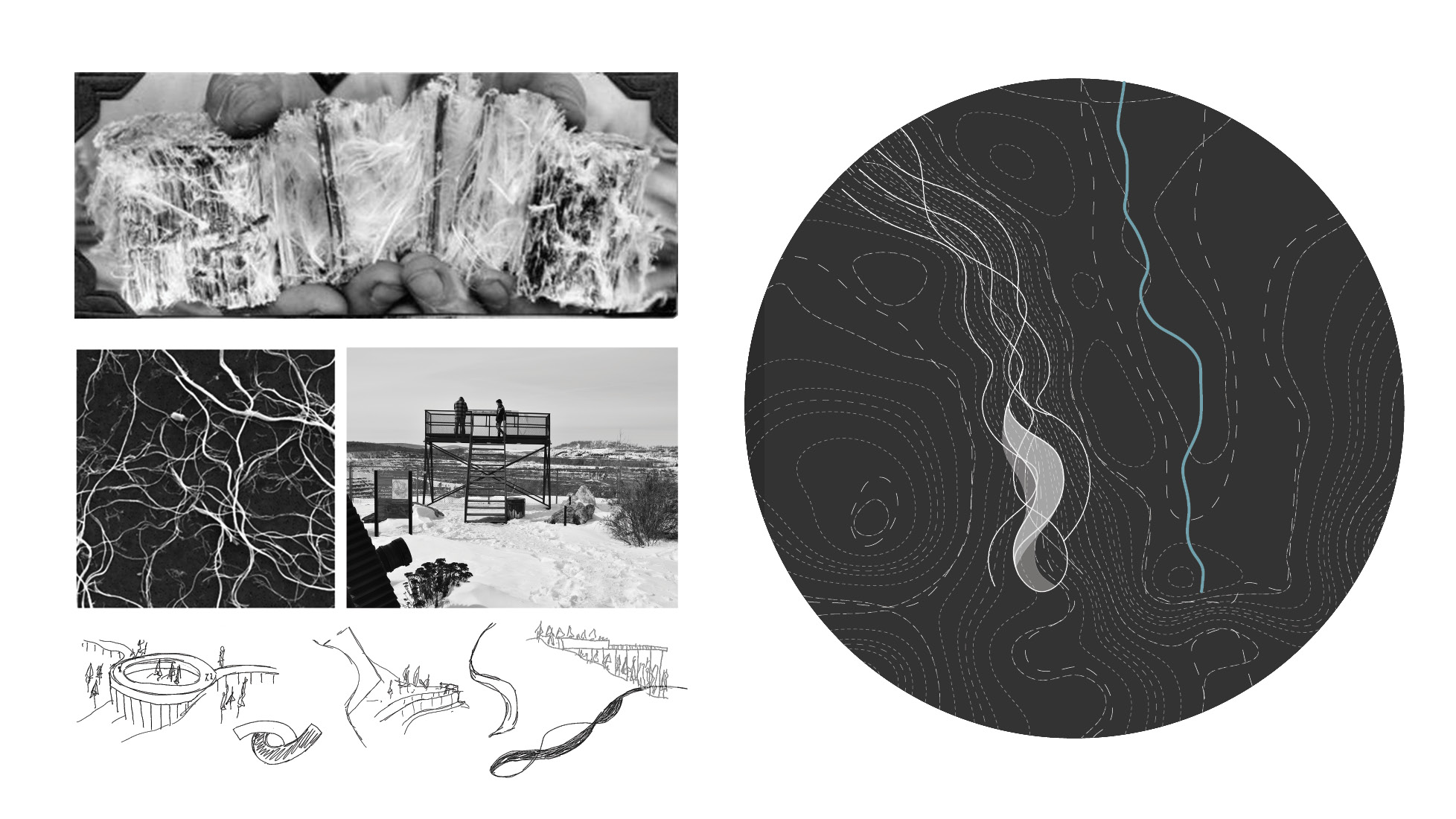

Examining the now Val-des-Source, its history and landscape, this project poses the question: Is it possible to harness the therapeutic properties of this landscape to promote healing? Can the land that causes so much trauma also be the source of healing?

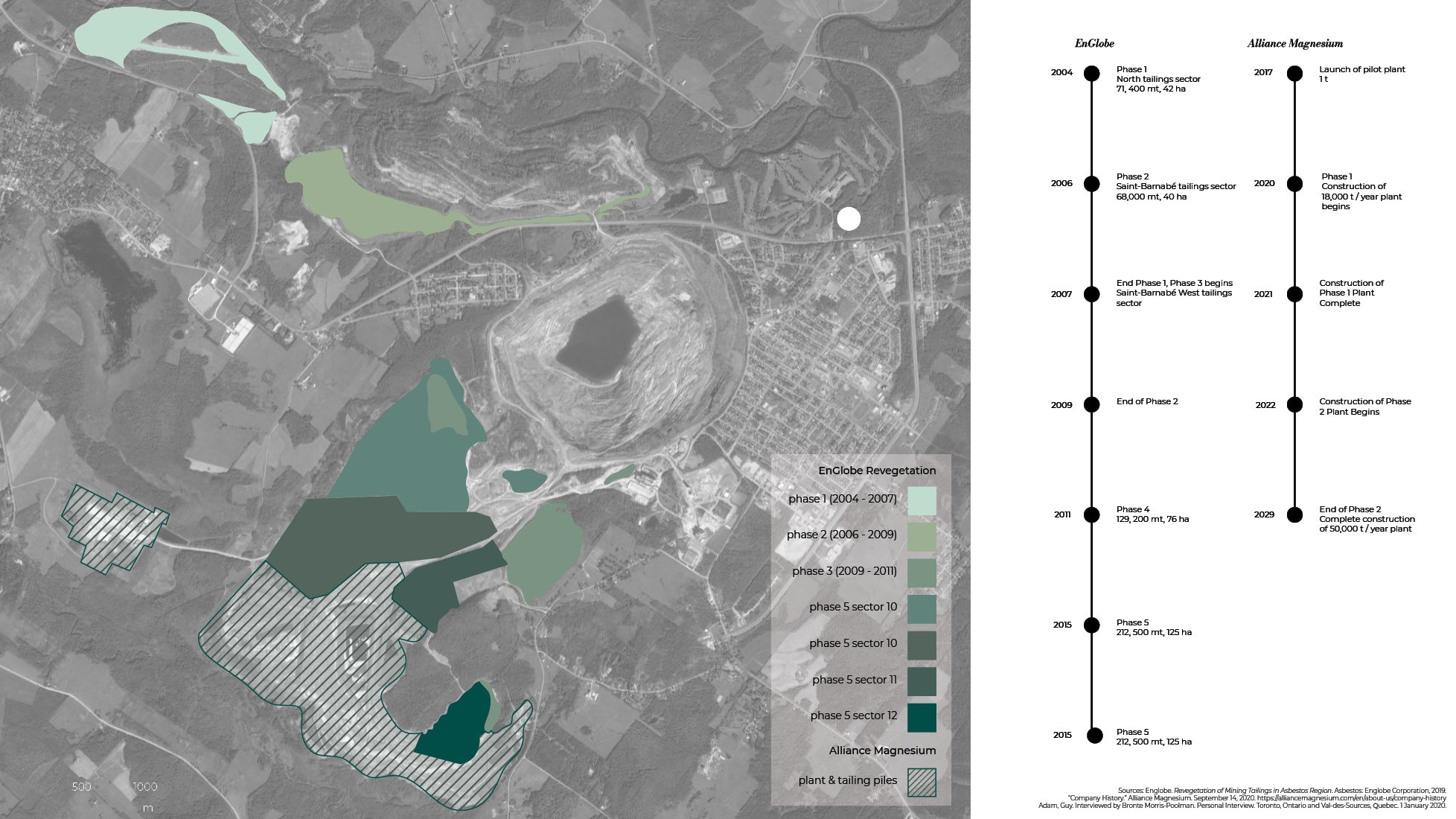

My project is part of a larger scheme that includes environmental rehabilitation that has been ongoing by a company called Englobe since 2004. Only 5% of what was extracted from the mine was actually asbestos and the remaining 95% was left in tailing piles around the mine. These piles measure between 50 and 250 m tall and cover 800 hectares. They contaminate the landscape, plants, soil, wildlife, water, and air. EnGlobe uses recycled materials to form a soil topping that they use to cover the tailing piles and revegetate. Today, over 12,000 trees have been planted, and 200 hectares have been revegetated. Another element of the overall scheme is Alliance Magnesium. They are a company that extracts magnesium from the tailing piles using green technology and, in the process, destroys the harmful asbestos fibres. These two projects aim to heal the landscape, while my proposal aims to heal the people.

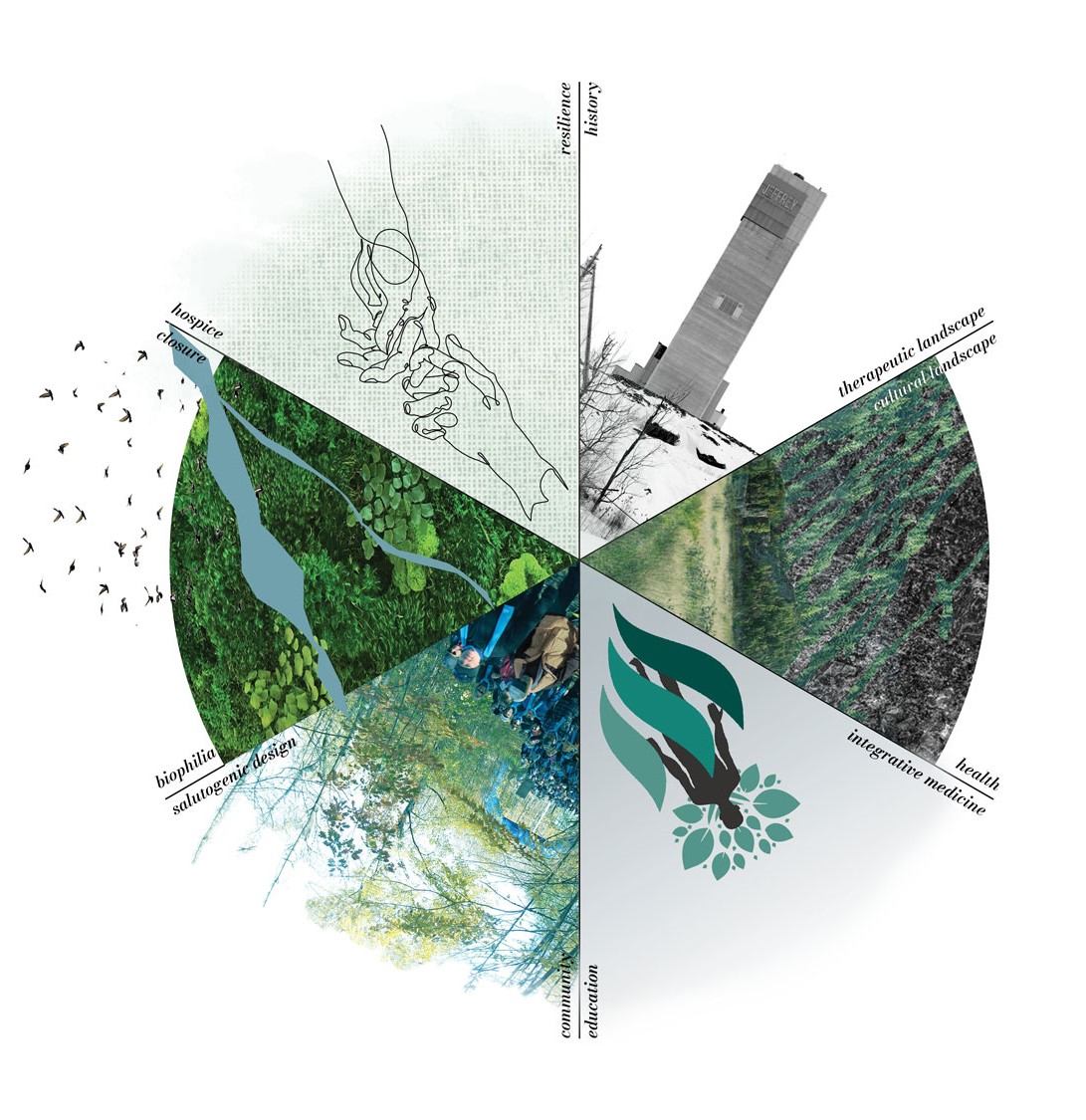

The Centre for Human and Environmental Health is part of a larger goal to transform the town into one focused on the research and treatment of asbestos-related diseases, palliative care for patients, and environmental rehabilitation. As a hospice and clinic that specializes in asbestos-related diseases, it will be the first of its kind in Canada. The centre recognizes the town’s rich history and resilience by including a new home to the geology and mining exhibit. It sees the land as both a therapeutic and cultural landscape. The centre uses integrative medicine and values nature in the healing process. It promotes a healthy community by raising awareness about asbestos exposure and providing support. It intrinsically integrates salutogenic and biophilic principles into the design to create a symbiotic relationship between health and landscape. Finally, it provides closure for patients and families at end of life and even includes a memorial.

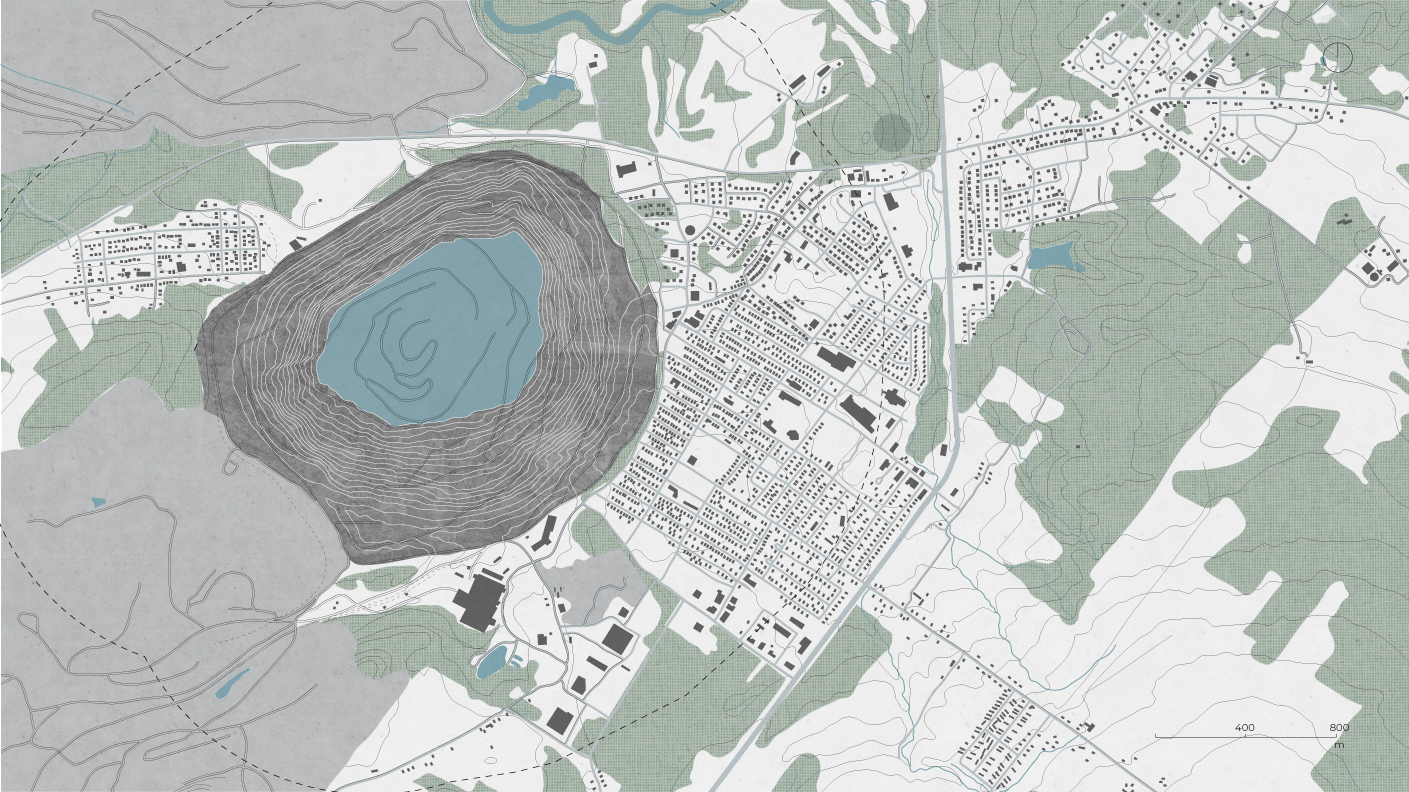

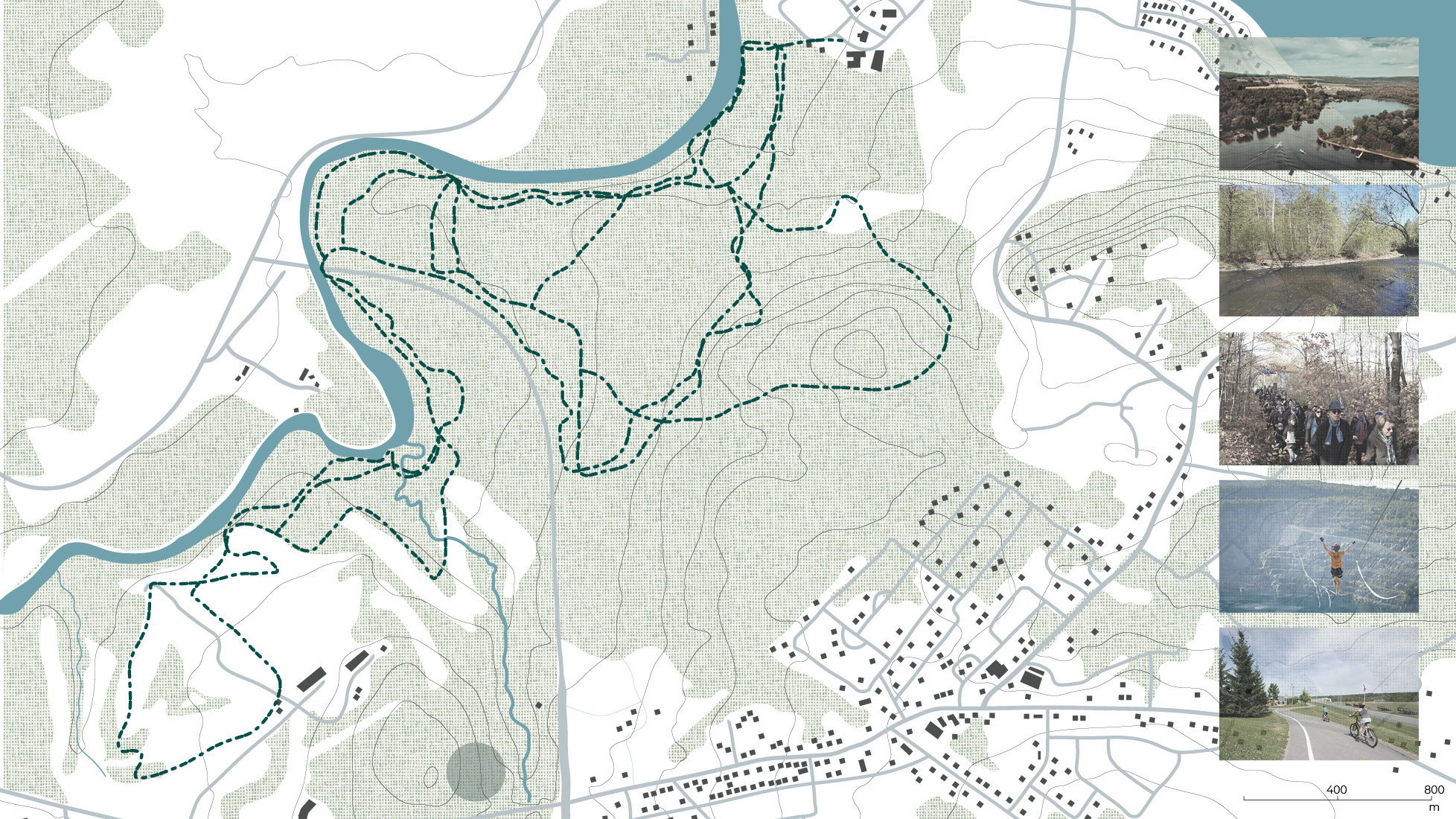

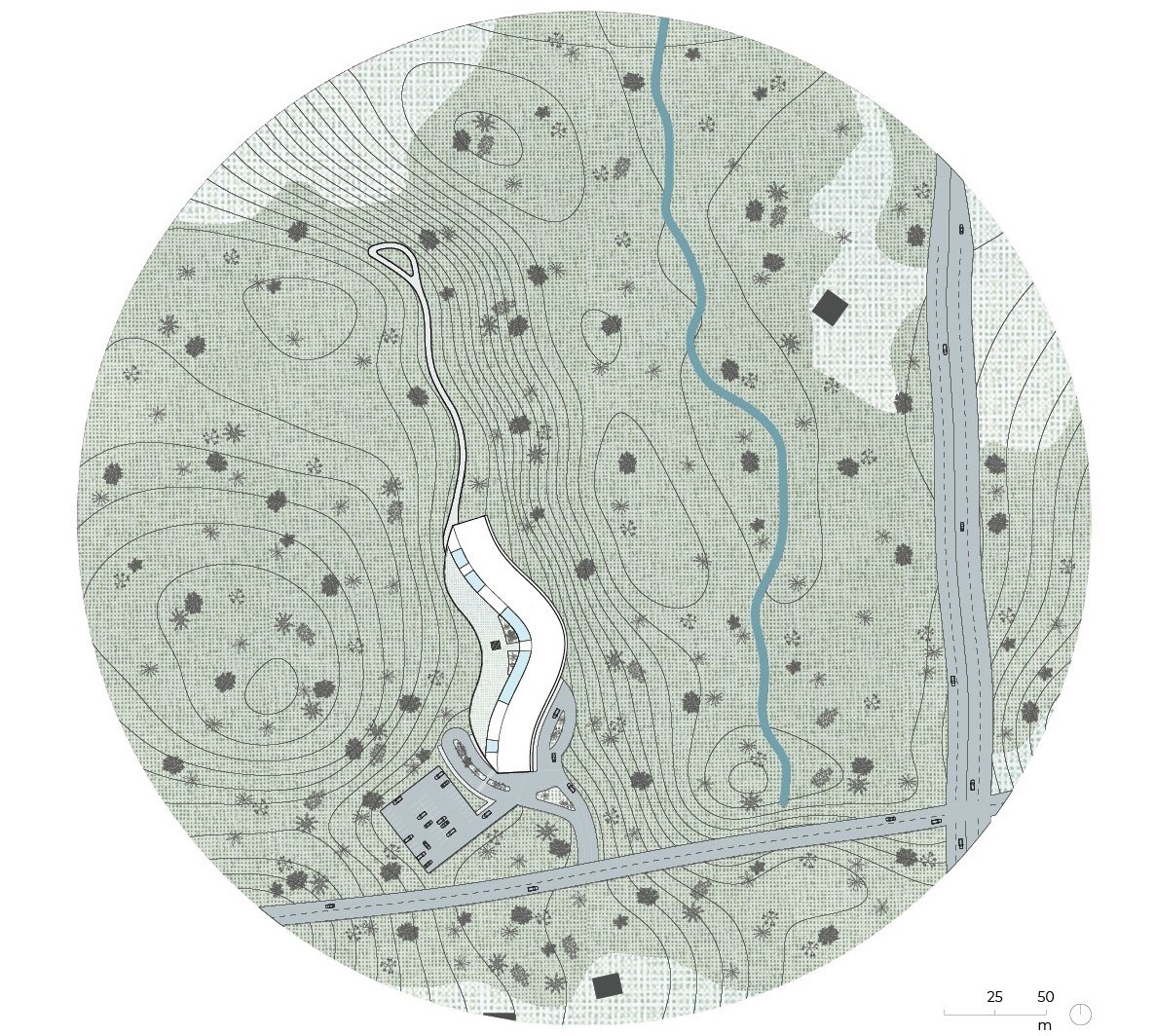

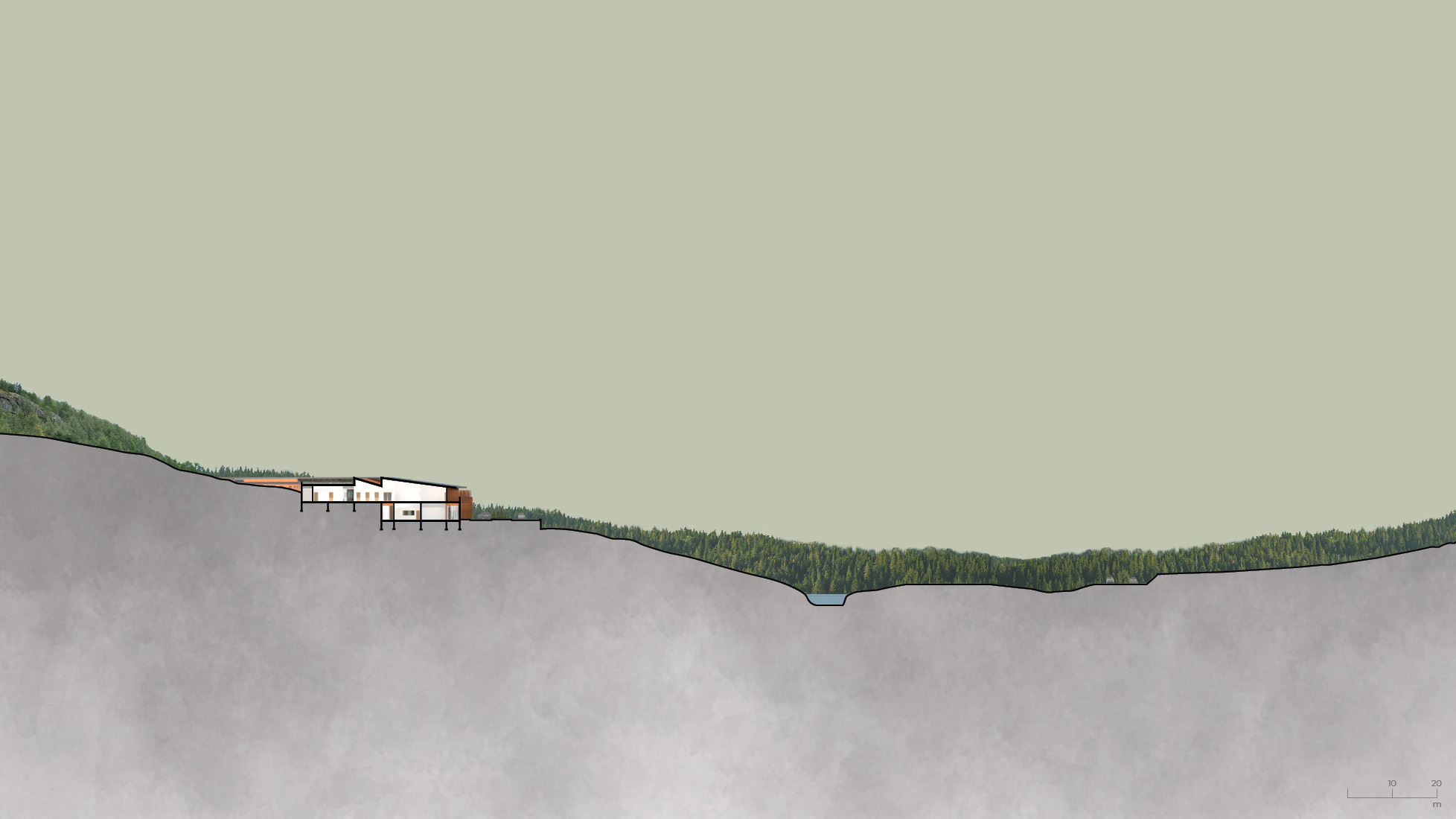

Research shows that by moving 1 km away from the open pit there is a significant decrease in the likelihood of airborne asbestos fibres as marked with the dotted black line. This was an important consideration when picking the site marked with the grey circle, which is within a relatively untouched natural area of the town. It can be difficult to look past the mine and find beauty in the town’s landscape, but for residents of the town, they are not defined by the mine. Residents find beauty in their mining history as well as natural surroundings and both should be valued equally. Accordingly, outdoor activity is an important part of everyday life. As such, the site was chosen because it is close to hiking, cross-country skiing paths, golfing, a river, and a lake.

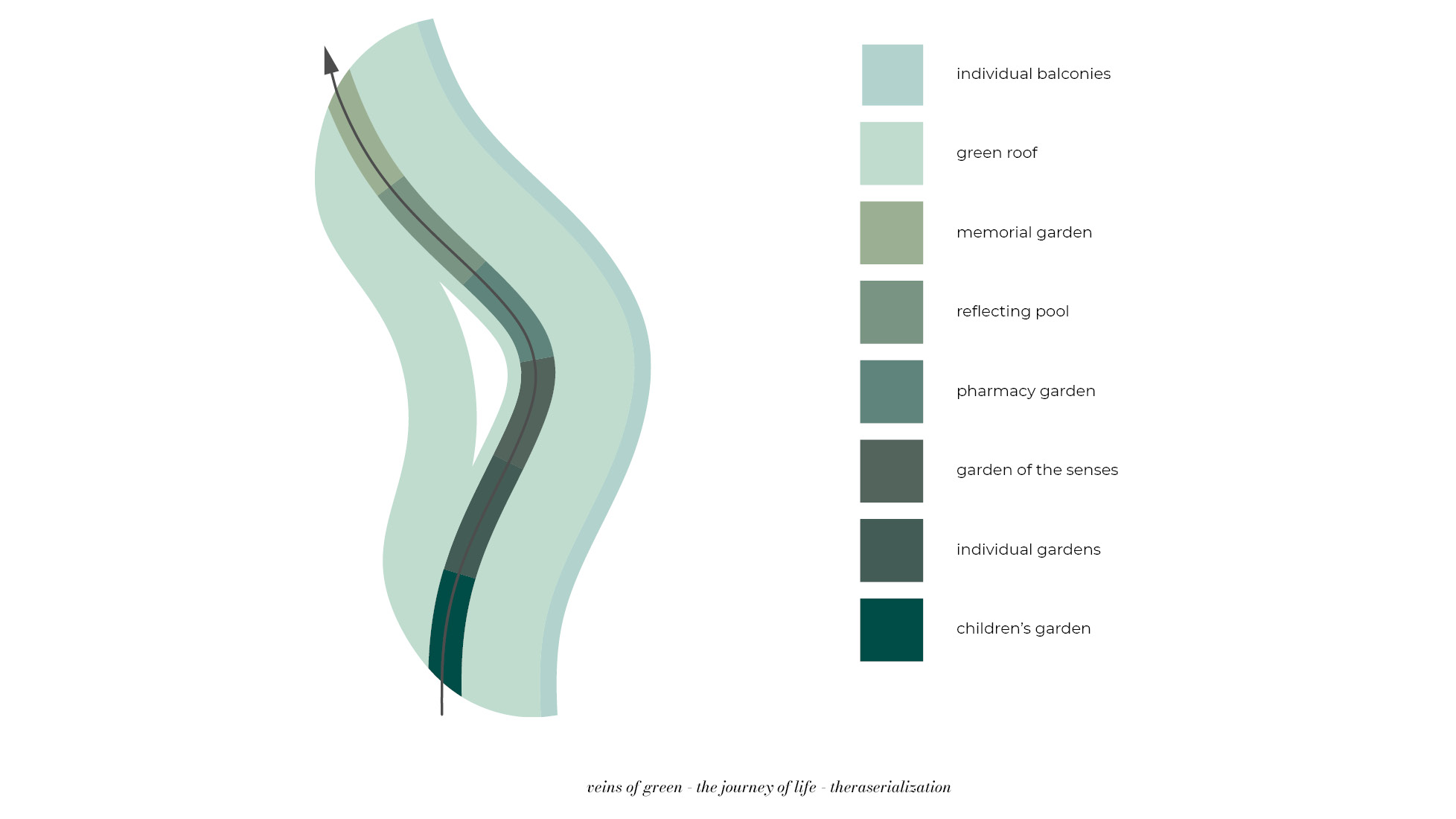

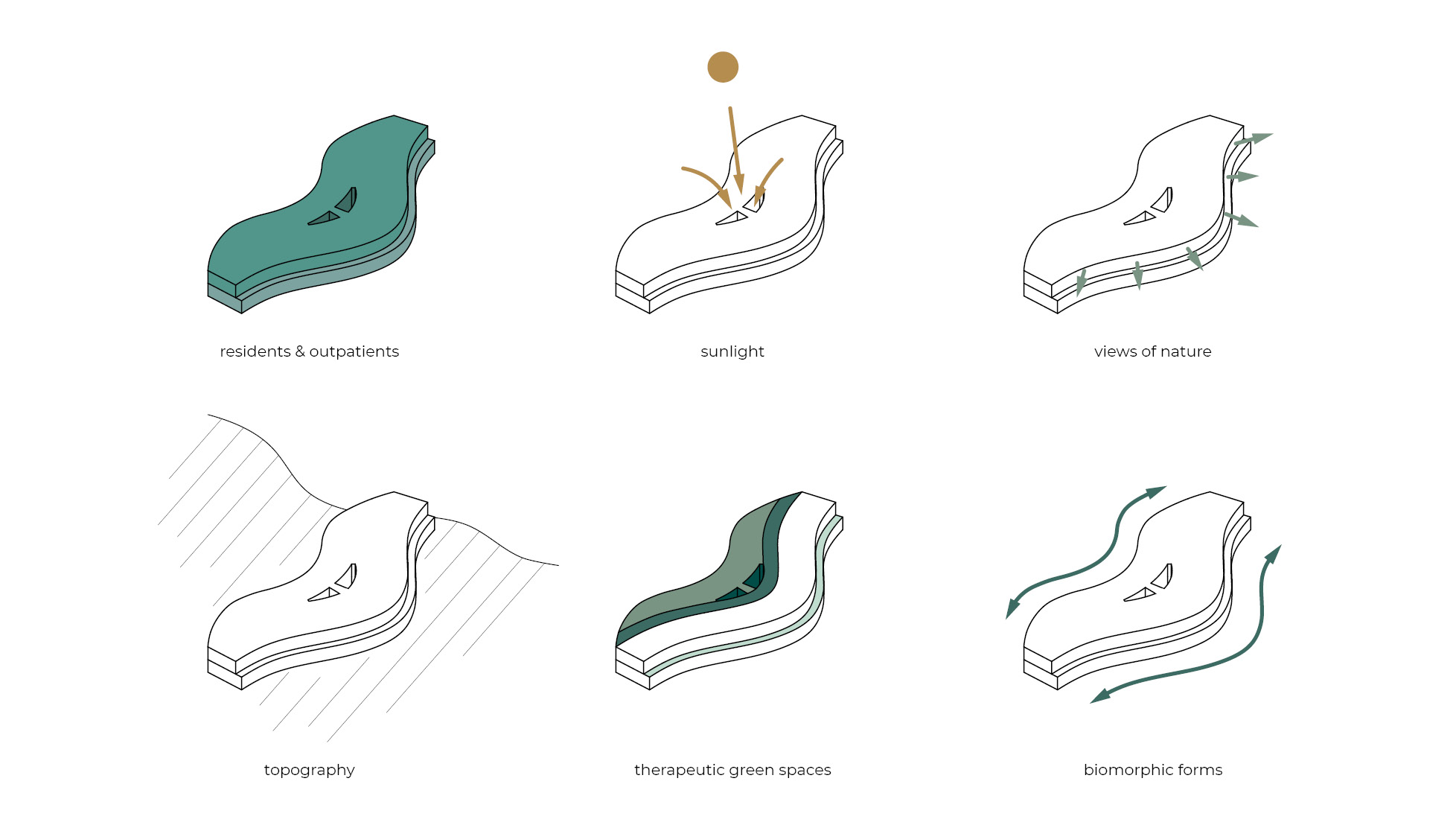

Asbestos is thought of as a hard, brittle, rock. However, asbestos is actually fibrous and soft. The intention of the design was to have the building grow from the topography and exemplify these sinuous characteristics. It was also intended to be a departure from the rectilinear industrial architecture in the town. Serpentine chrysotile asbestos is found in veins within the rock. The concept of the design was to include veins of green within building to theraserialize the spaces. This vein contains multiple green spaces that weave through the building and represent the journey of life – the children's garden, individual gardens, garden of the sense, pharmacy garden, reflecting pool, memorial garden as well as a green roof and individual balconies.

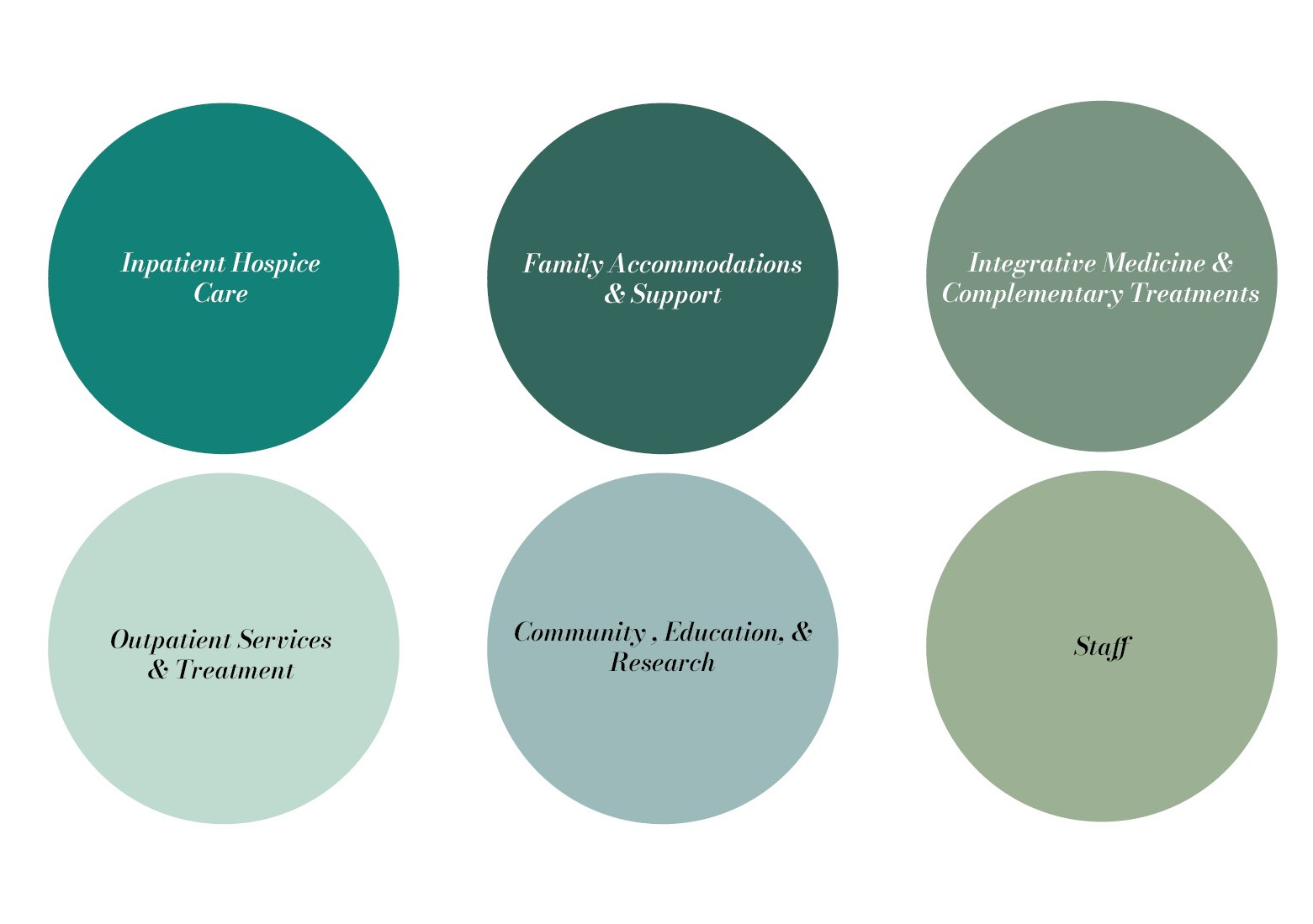

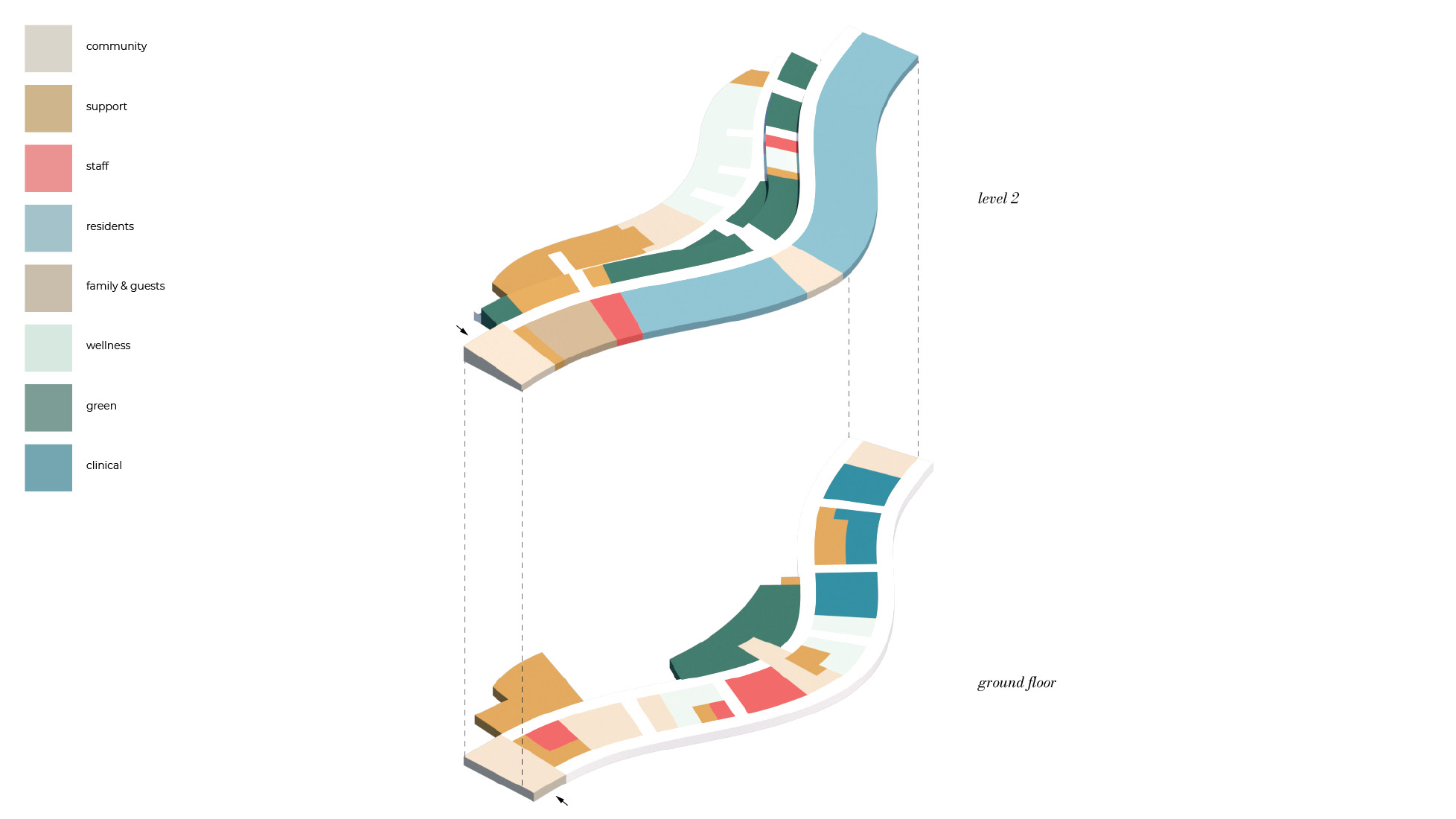

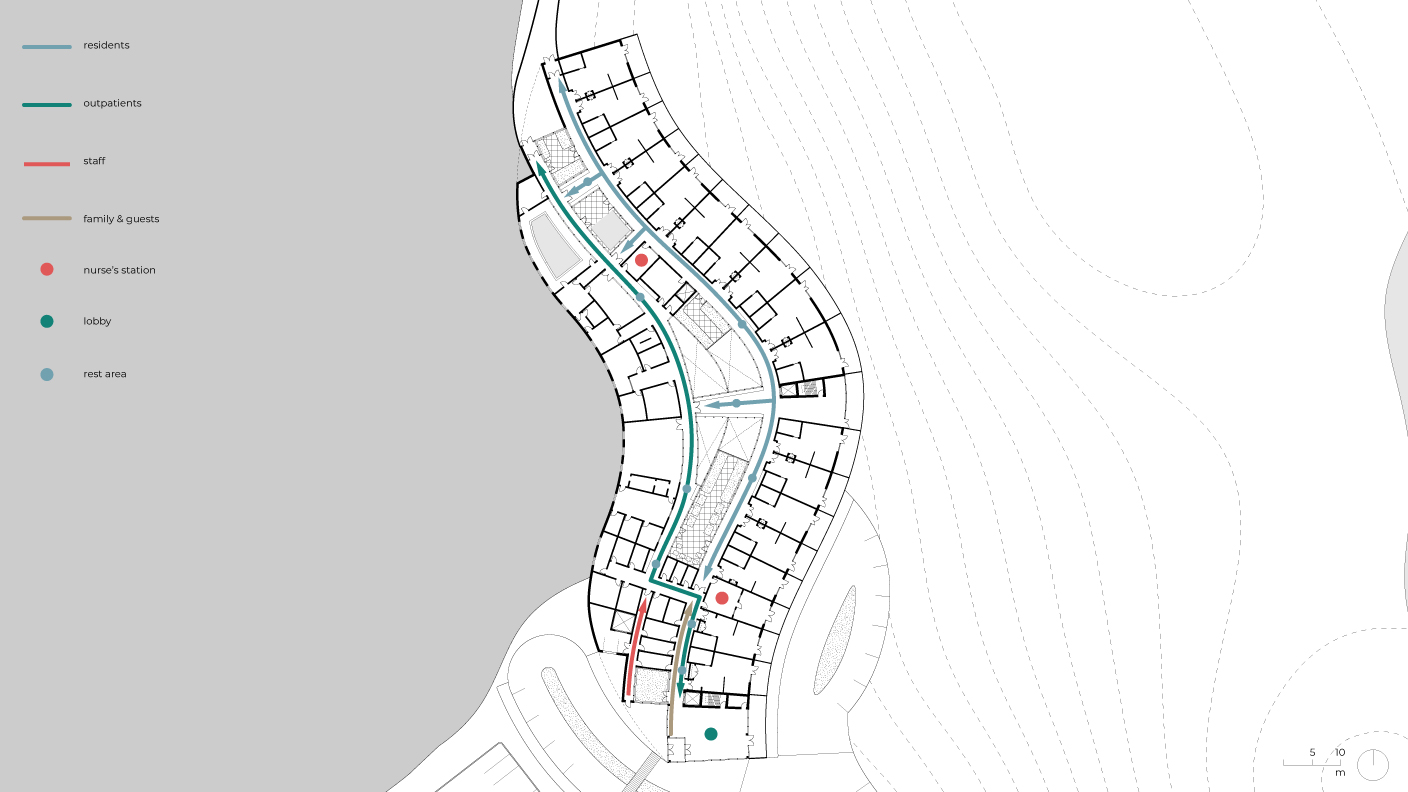

The centre is split between 2 main programs: a hospice for 15 patients and a clinic for outpatients. It serves patients, their families, the greater community as well as members of neighboring asbestos mining towns of Thetford Mines and Black Lake. The clinic provides screening, diagnostic, and disease management services. Since asbestos-related diseases are not curable, it is important to include services that help improve quality of life such as methods of integrative medicine and complementary treatments. The centre also provides community focused programming including education, support groups, research, air testing, and geology exhibits.

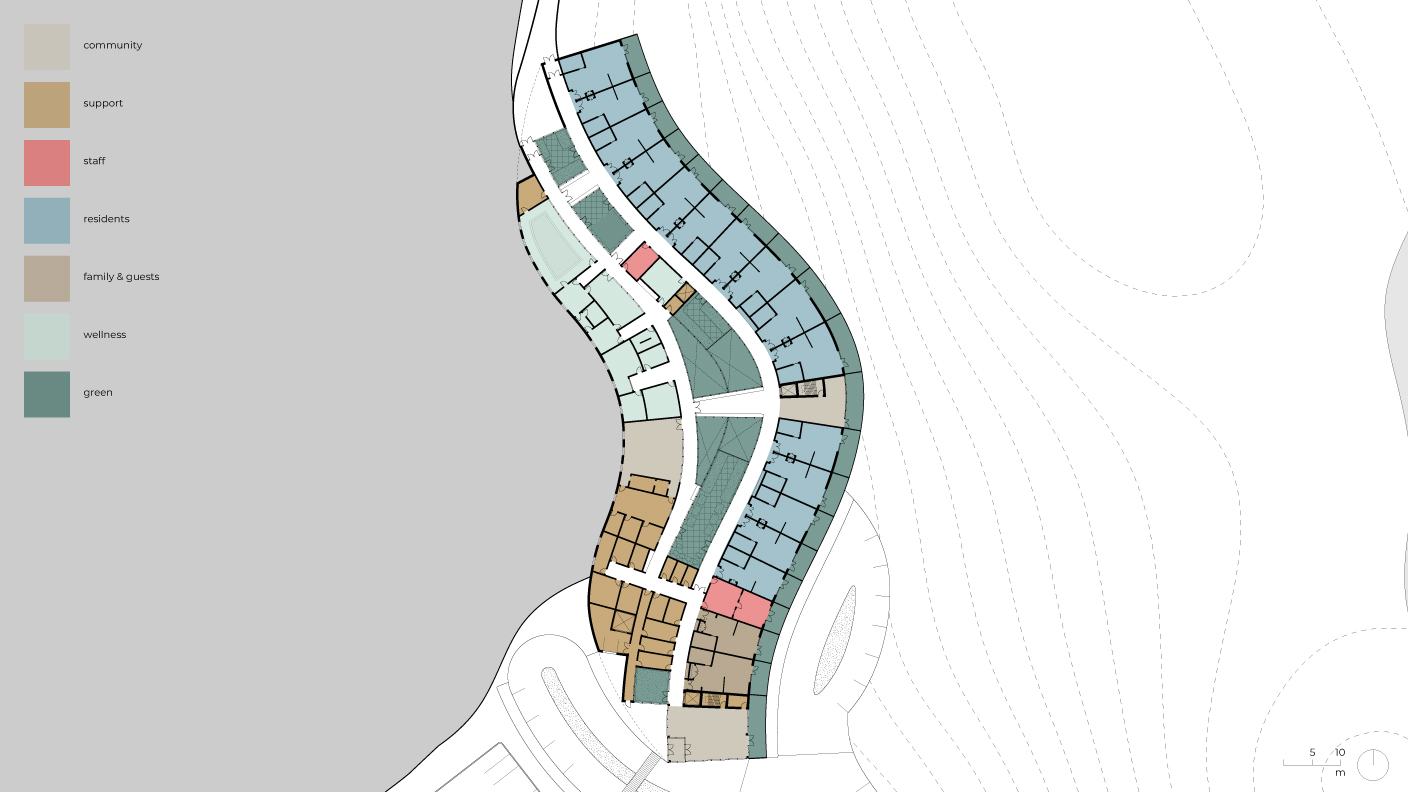

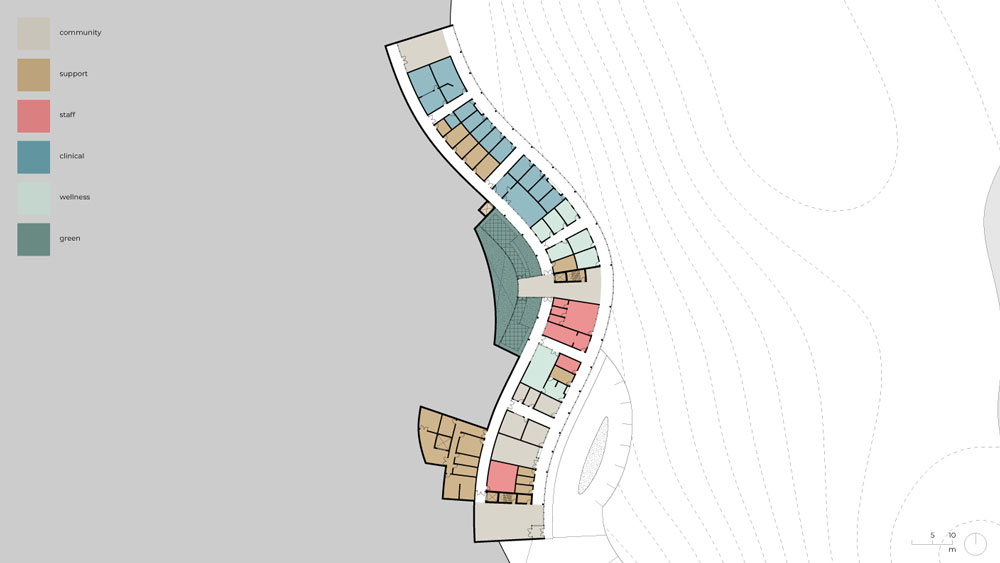

Level 2 Floor Plan – Hospice

On level two, the hospice, there are fifteen patient rooms with their own private washrooms, two guest rooms with private washrooms as well as the primary nurse’s station with its own private balcony. The wellness programming includes a religious space, a grieving room, an art studio, and art gallery to display patient work, a music room, a library, a hydrotherapy pool as well as a series of all-season green spaces. The two resident lounges both have views of the atrium in the center, and one has a public balcony space. One of these lounges is also the dining room where patients can eat together. In each patient room there is a bed area, washroom, kitchenette, dining area, balcony and living area with a couch that pulls out into a bed for family.

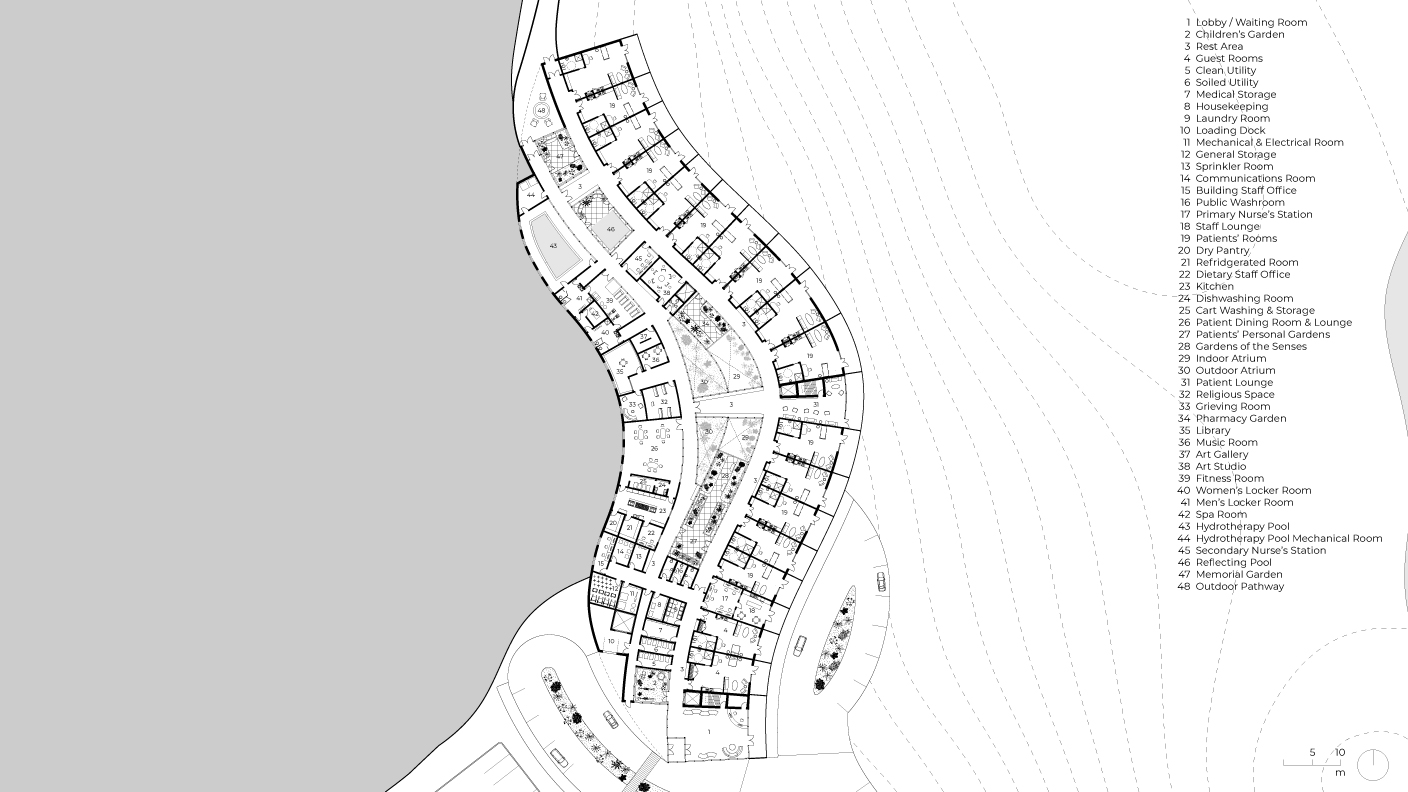

Level 1 Floor Plan – Clinic

On level one, in the clinic, the community functions are located close to the entry. These include a community hall, classrooms, and meeting rooms. Most of the staff spaces are also on this floor including the staff lounge, lockers, washrooms, kitchen, and offices. In the middle of the plan is the atrium that not only includes a winter garden, but also a geology exhibit which is currently in the town’s library and is not safety exhibited so it would be moved here, and all minerals would be properly contained. In terms of wellness, on this floor there are therapy and counselling rooms, a sensory immersion room, a meditation space, and a fitness room. The clinic has all the typical programming you would expect for a facility that screens and manages asbestos-related disease such as a pulmonary function lab, diagnostic, treatment and examination rooms, an x-ray room, and a CT scan room.

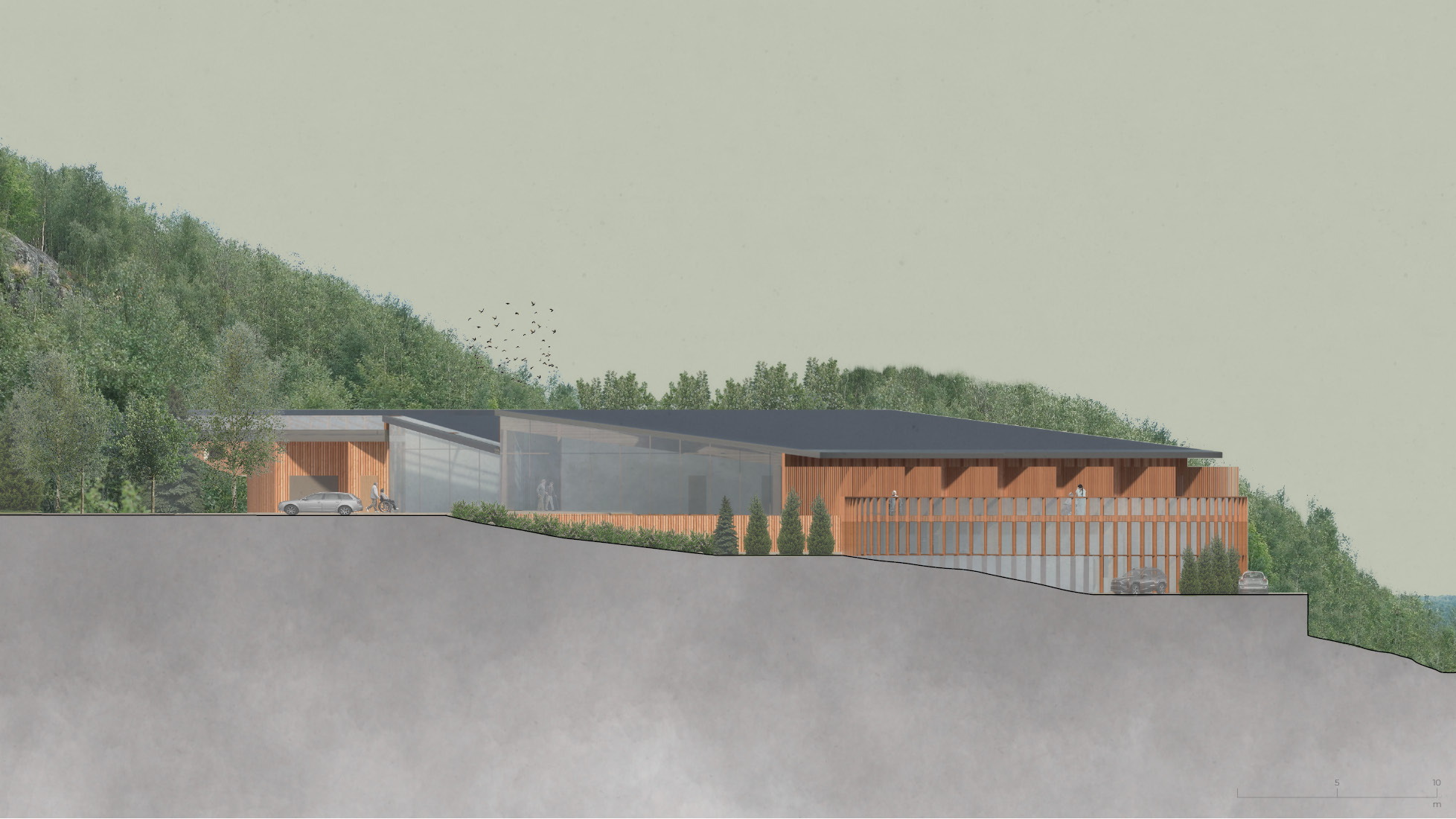

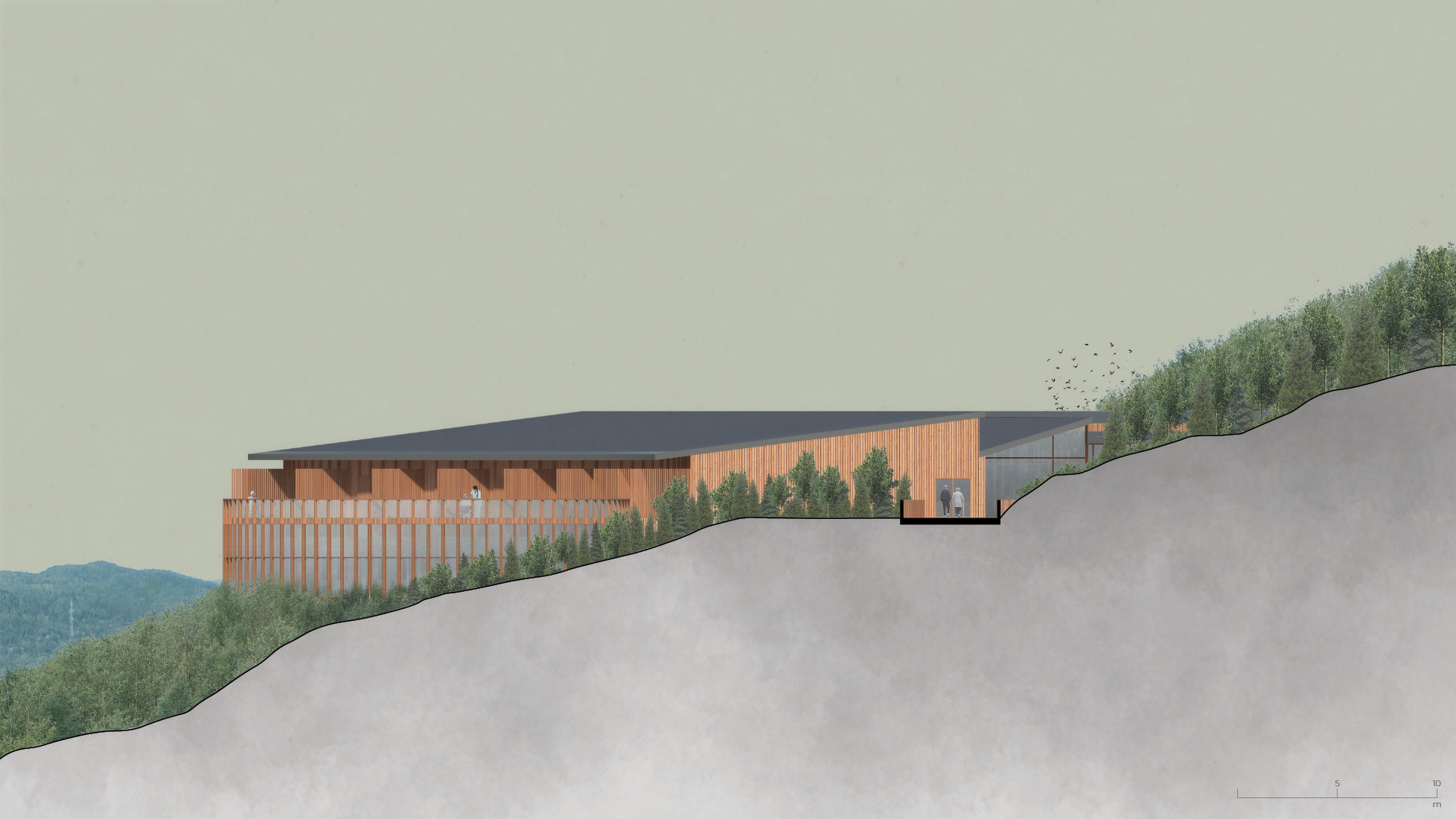

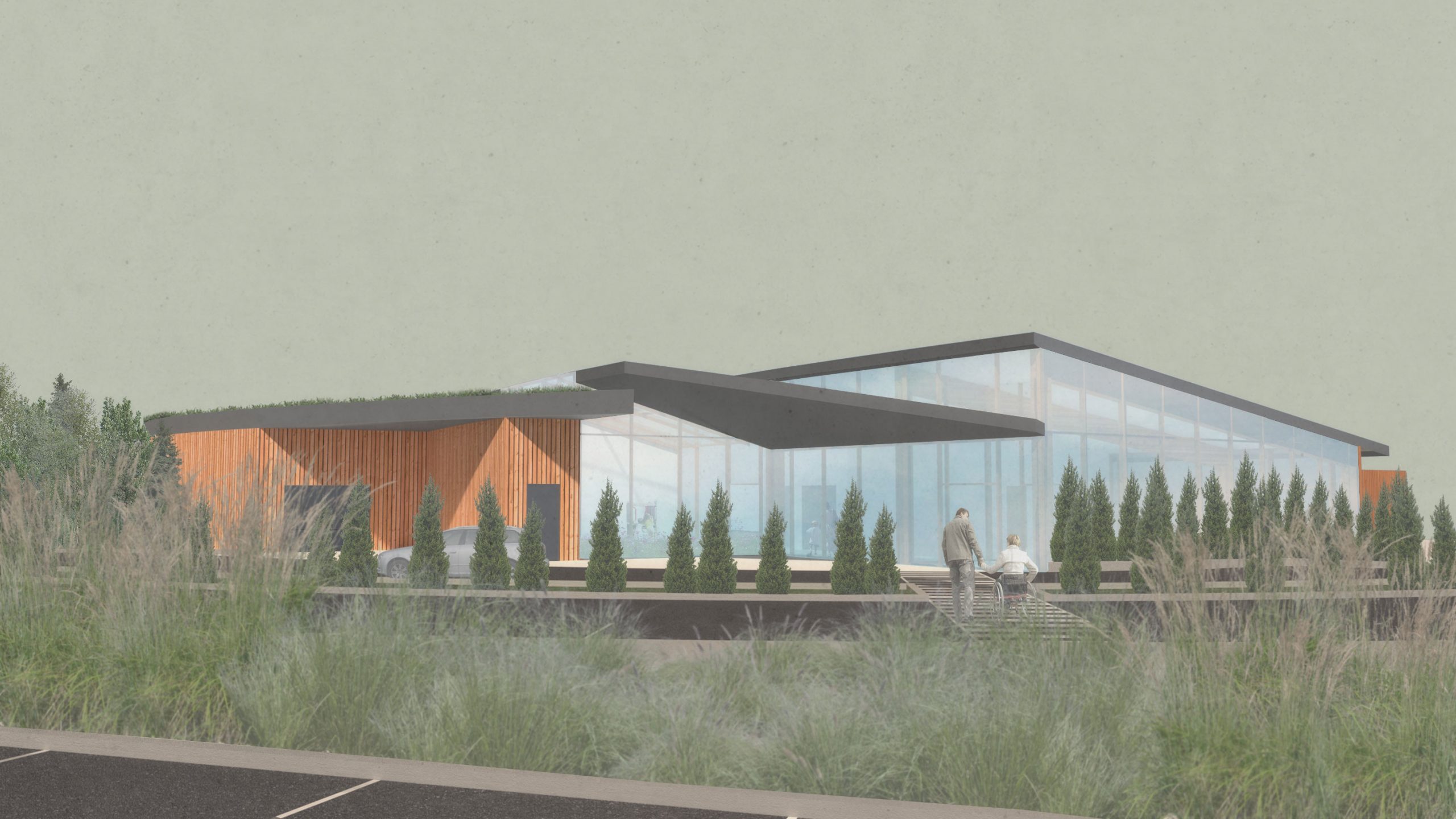

The east elevation faces down the hill towards the river and lake providing the best views from the site. The low, curved profile of the building provides a lookout nestled in the woods and looks different from each angle. The entrance to the clinic can be seen on the ground level as well as the road leading up to the parking lot and separate hospice entrance. The second level is lined with private balconies for the patients, guests, and staff. The facades are treated with natural cedar siding and glass to blend in with the context. The roof overhangs two metres to provide a sheltered area for residents to sit outside and mitigate direct sunlight within the rooms.

The south elevation shows the entrance to the hospice and varying roof profile that signals the entrance to the building and follows the sloping topography. A series of planted areas and cedars shield the residents from viewing the parking lot and driveway. The green roof towards the back of the building is a continuation of the landscape behind it. The north elevation faces the outdoor pathway. The separate exits leading to the pathway from the residential and shared corridor on the second floor can be seen on this elevation.

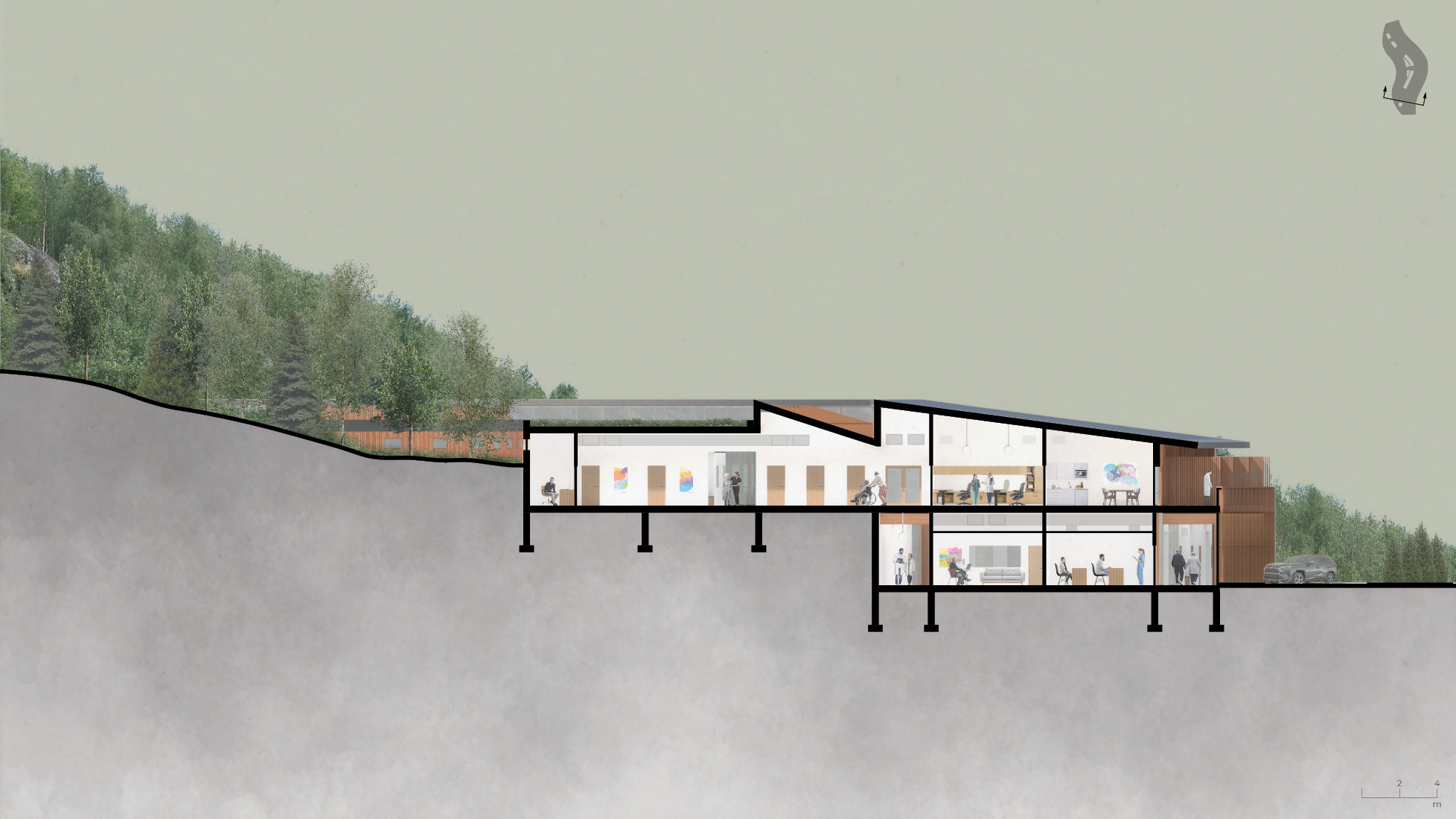

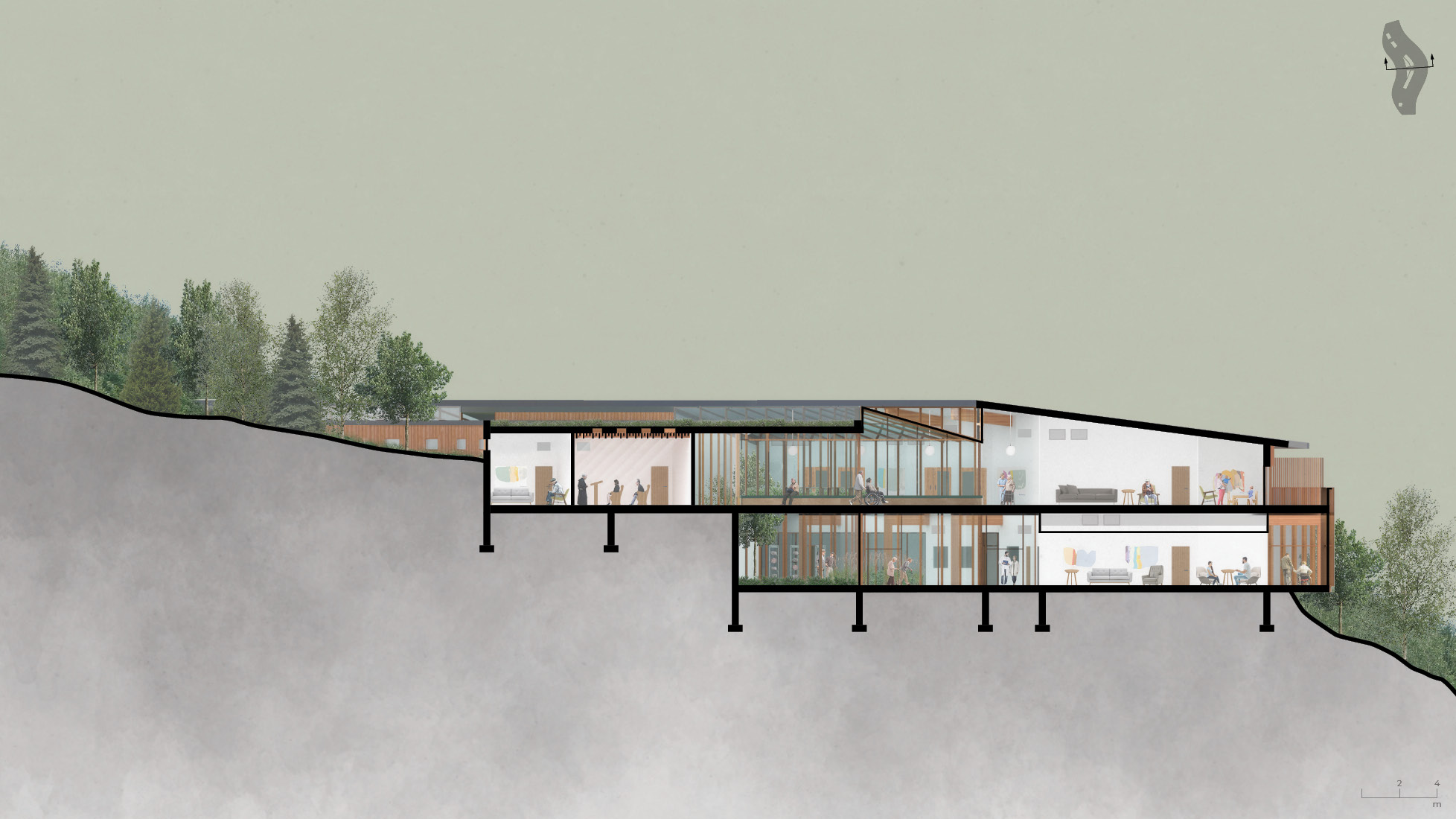

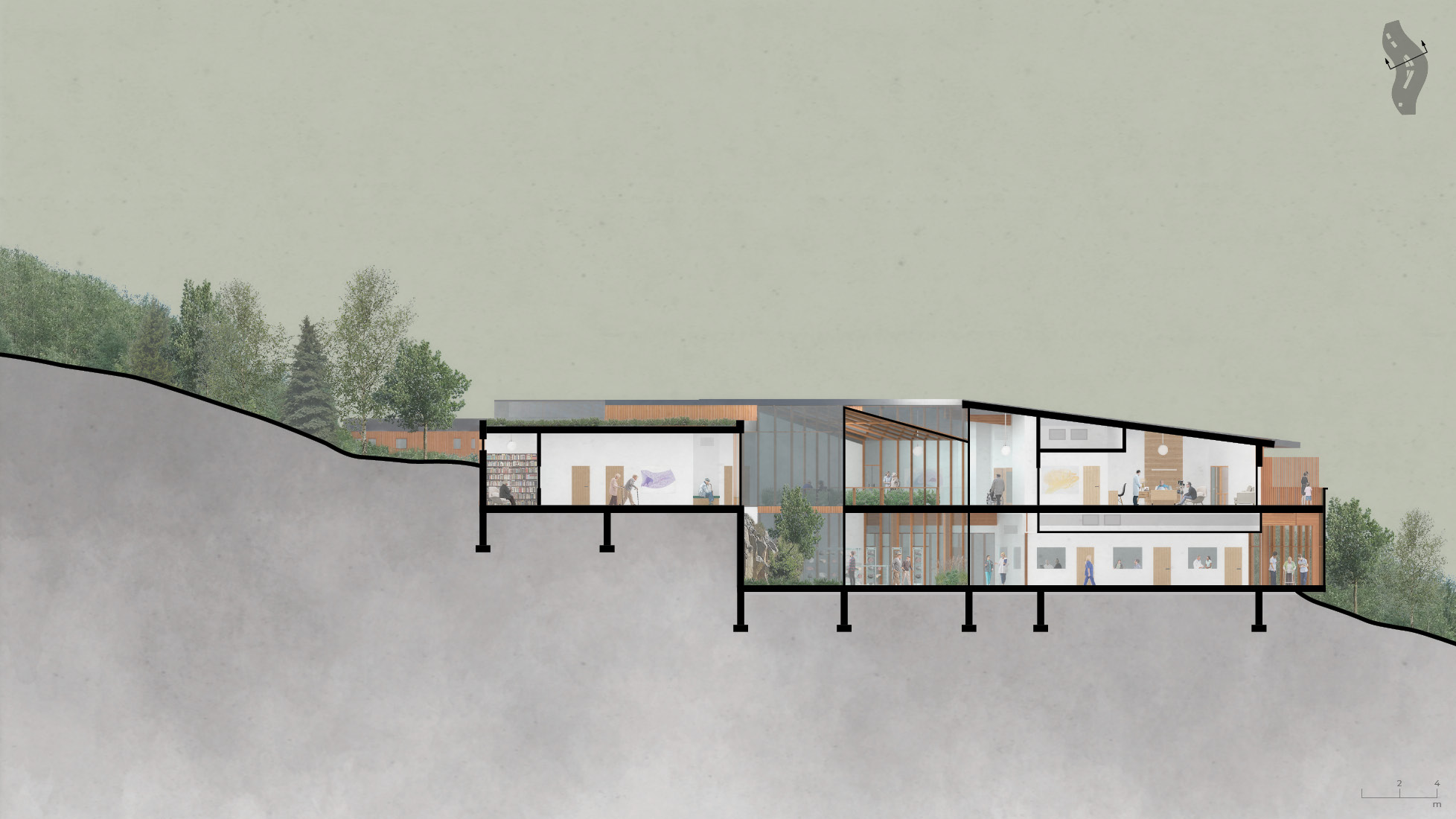

Moving from south to north through the building, the clinic can be seen on the ground floor and the hospice on the second floor. In the clinic, circulation is delineated between public on the east side and staff on the west side of the ground floor. In the centre, community programming can be seen first followed by staff spaces, wellness spaces, the atrium, geology exhibit, and finally clinical spaces. In the hospice, the resident rooms and nurses station line the east side of the building with green spaces through the middle and a variety of wellness and staff spaces on the west side.

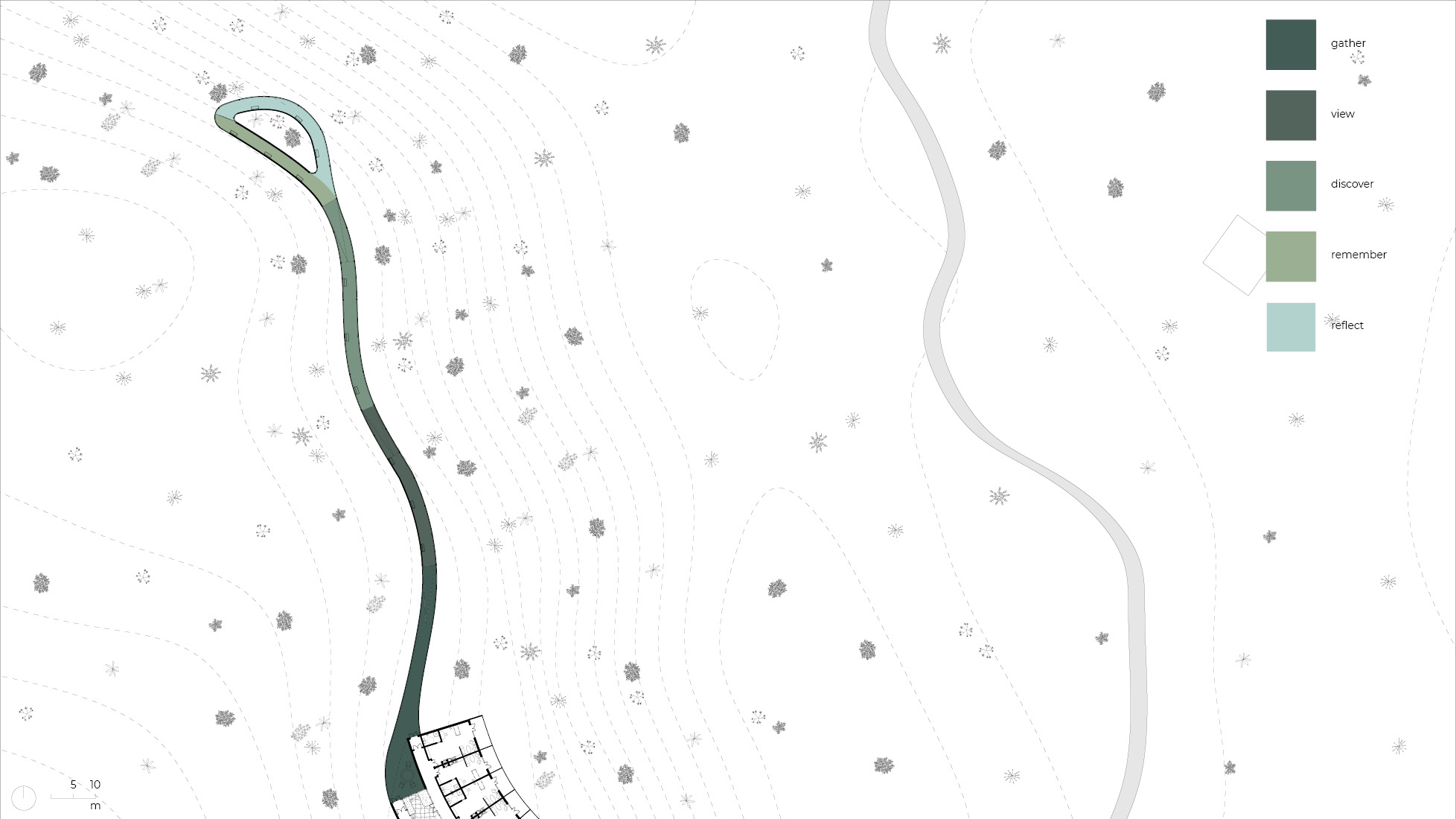

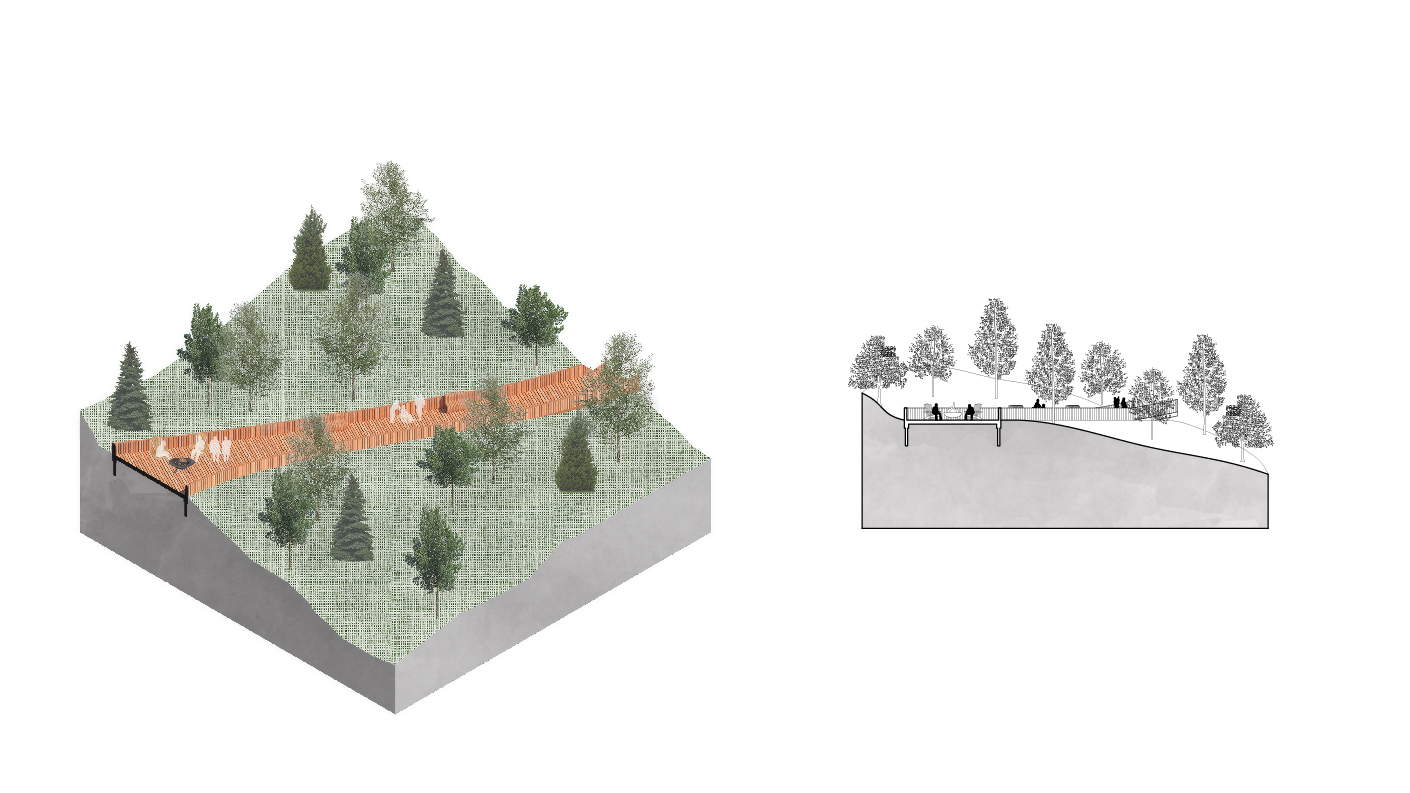

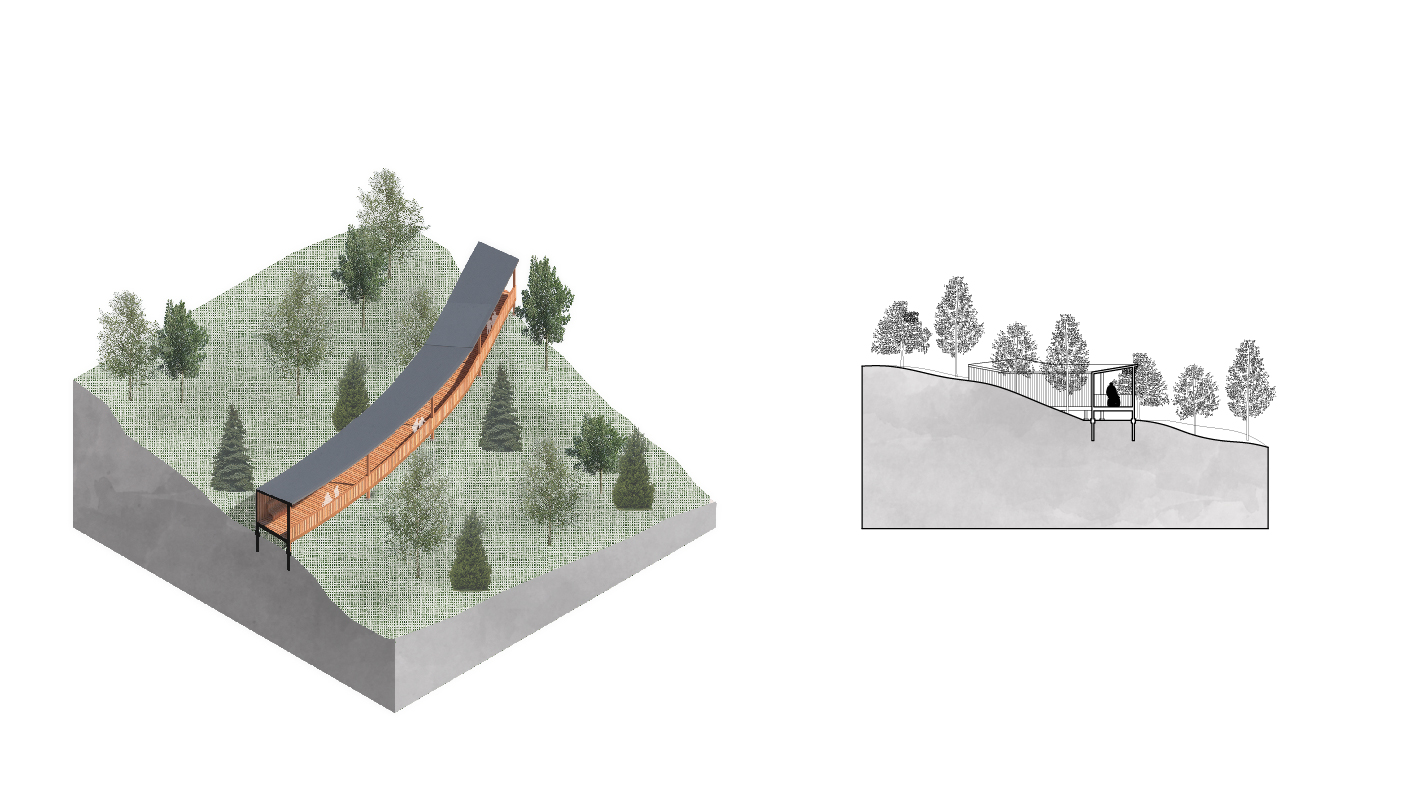

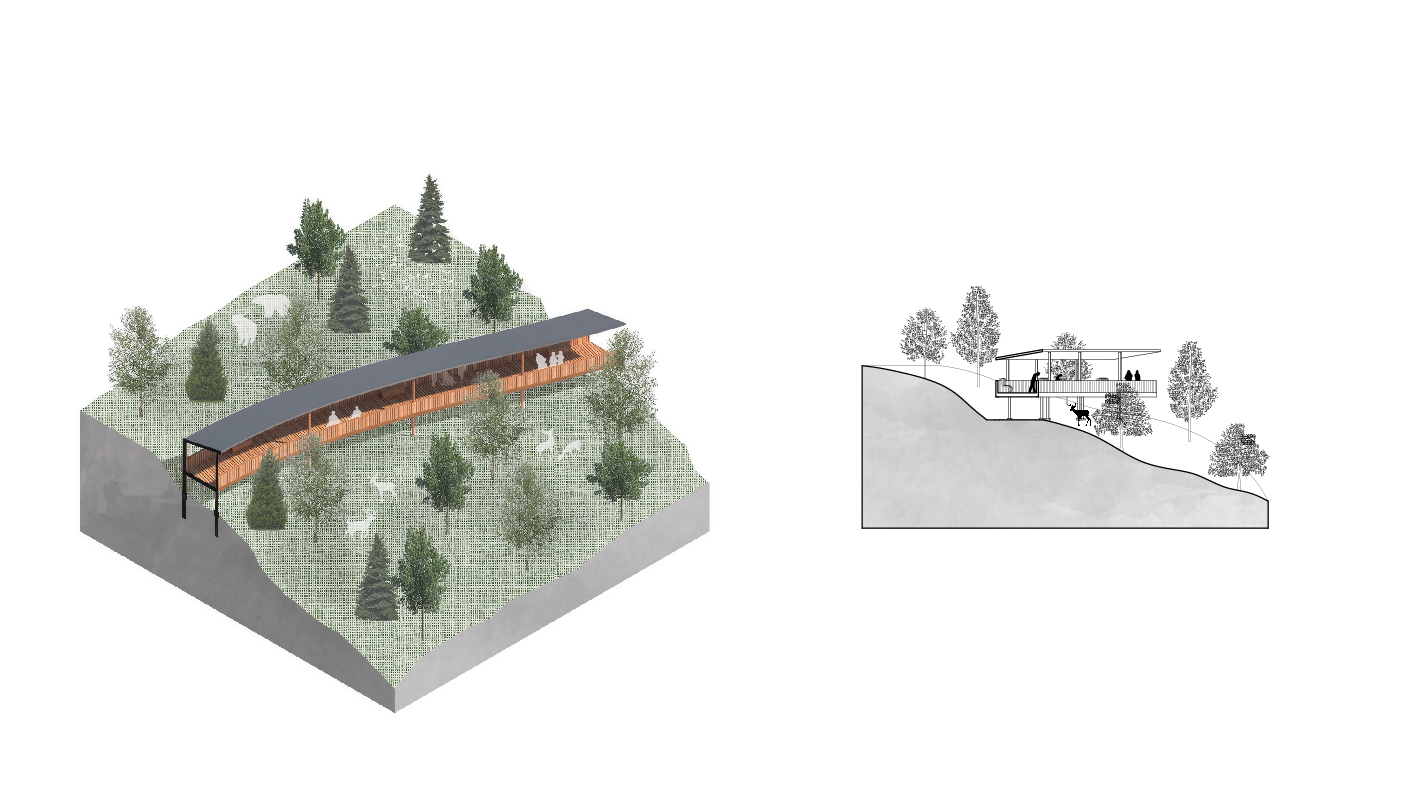

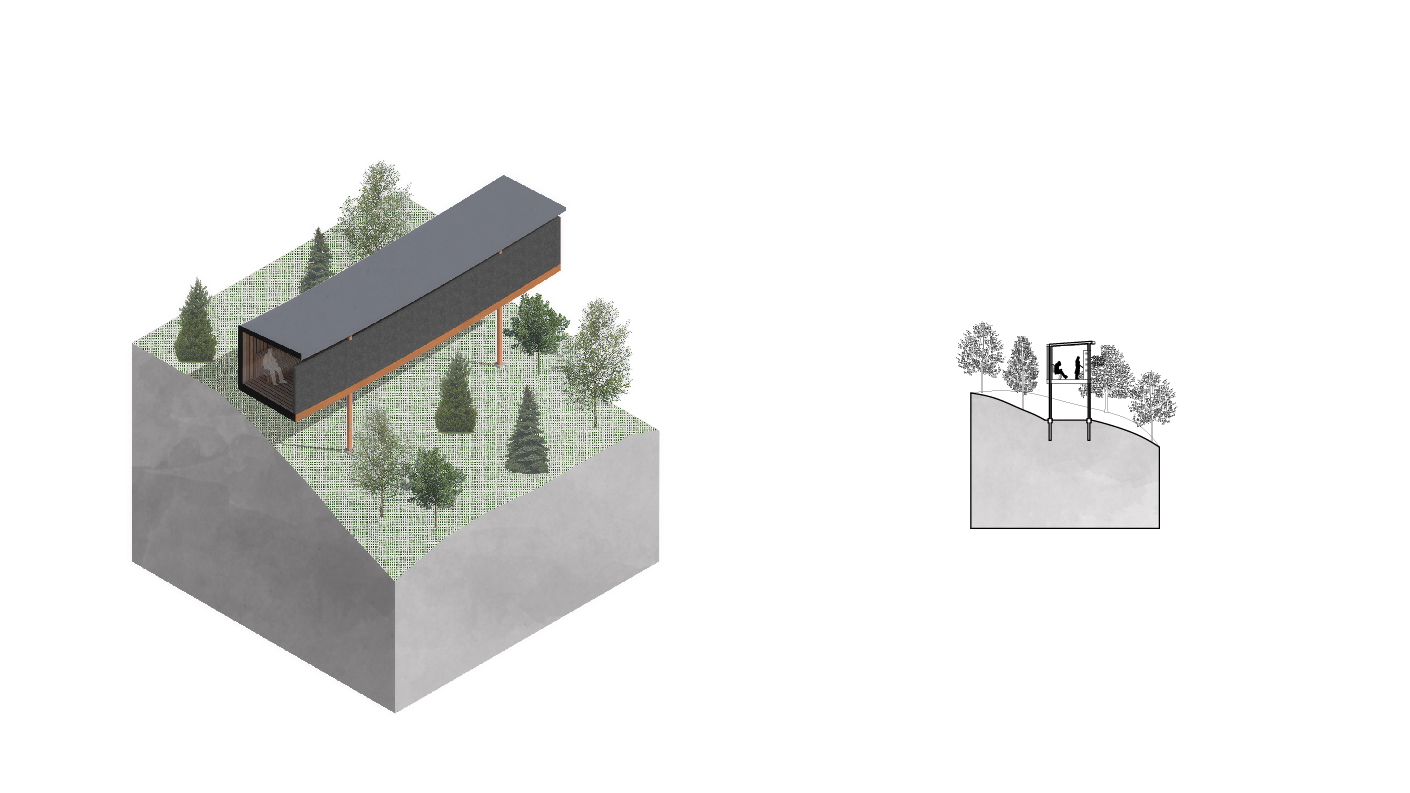

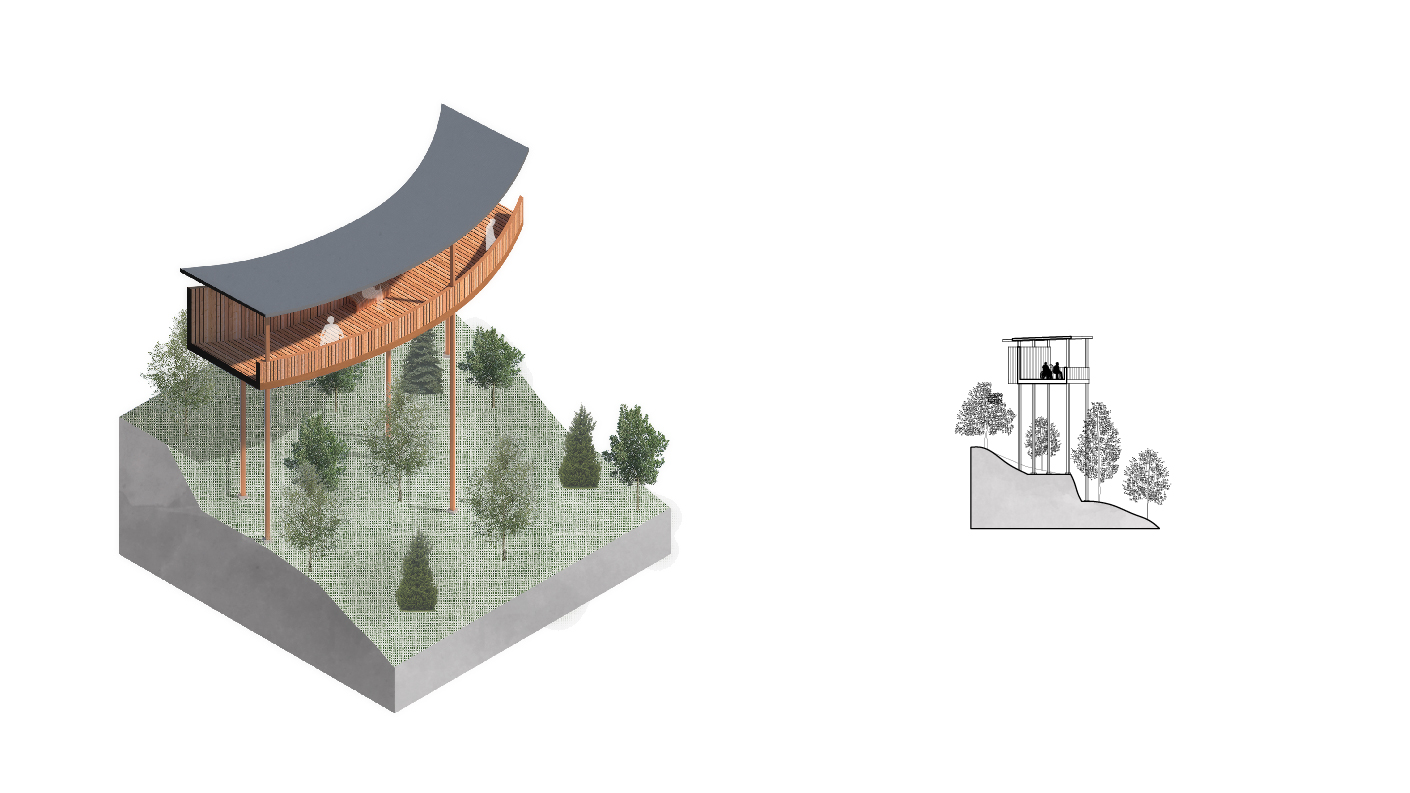

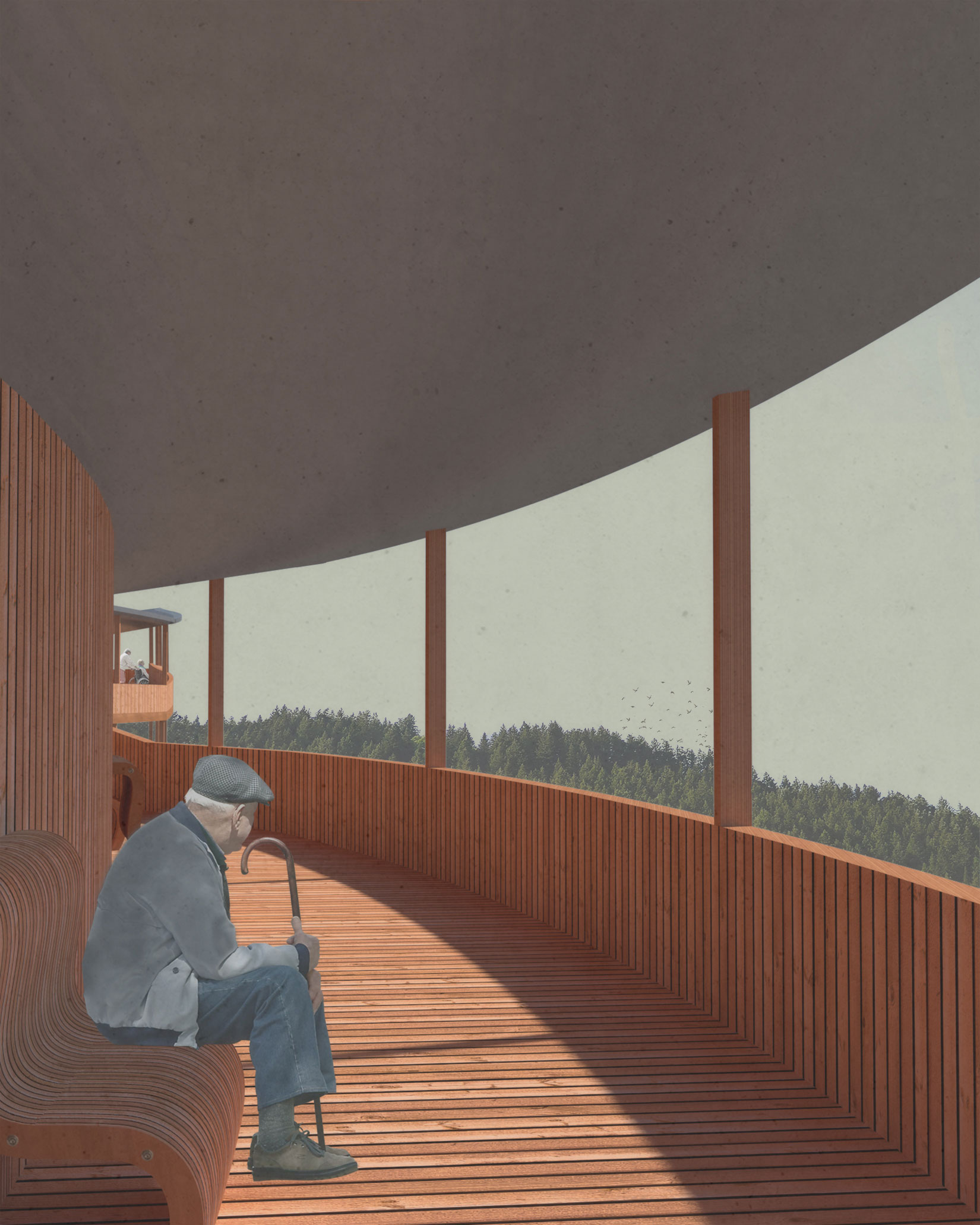

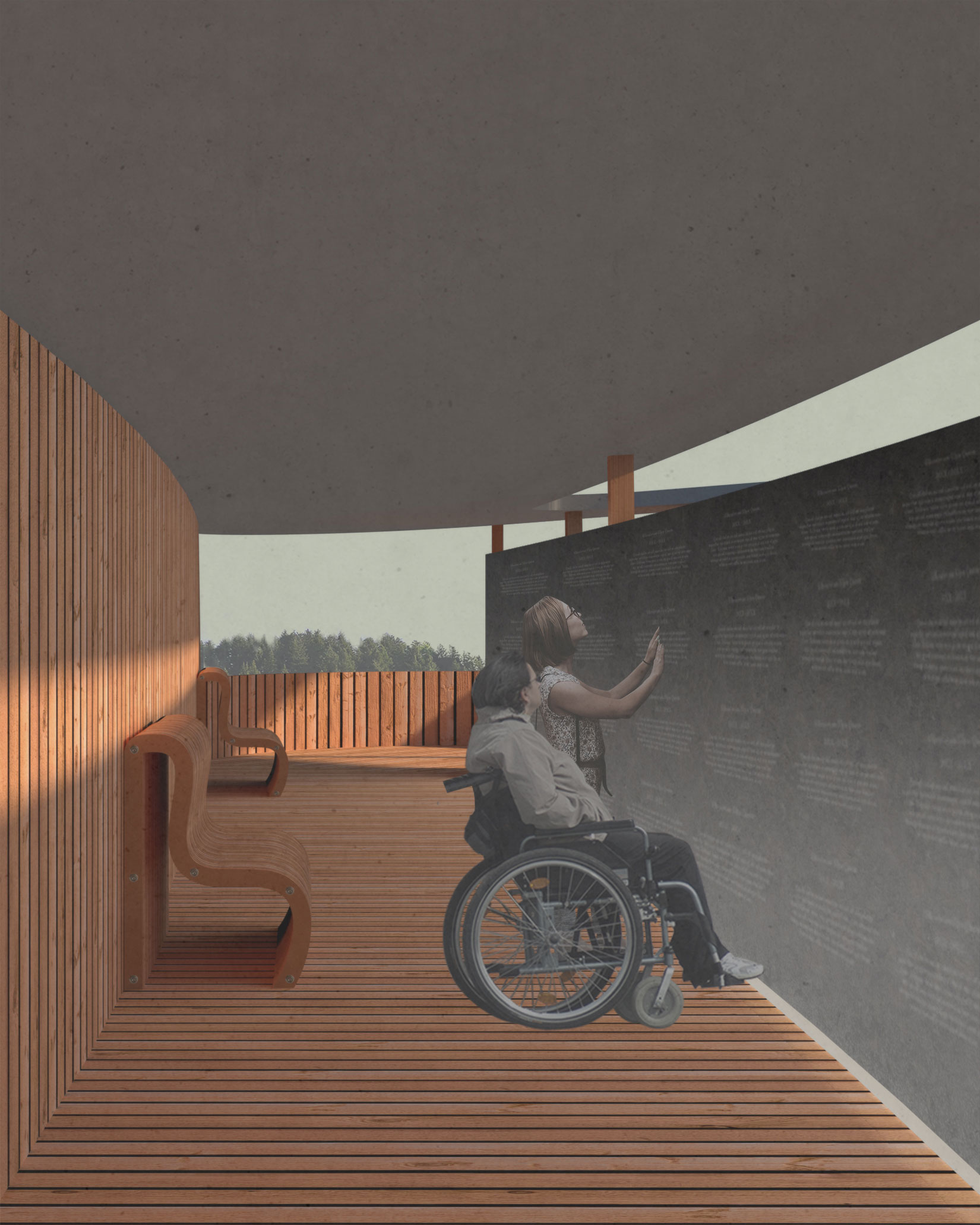

Enjoying the town’s landscape is very important to the people of Asbestos. However, those who have developed asbestos-related diseases find it hard to enjoy the outdoors as they used to because of their mobility and respiratory issues. This fully accessible elevated pathway gives residents of the hospice and patients of the clinic the chance to feel like they are hiking or snowshoeing the trails nearby. The ramping system rises above the tree level to provide views of nature and the large lake to the North-East. The pathway is entirely covered except for closest to the building so that it can be used for longer throughout the year. The pathway is divided into 5 different zones, and each is different in section. These zones are for gathering, viewing nature, discovering wildlife, remembering loved ones, and reflecting on the past. The curved circulation route provides opportunities for mystery about what is around the corner and matches the topography lines.

Gather: The widest area of the path is at the beginning where the two circulation routes on the second level join. The residents and patients are invited to gather together here at the fire pit.

View: In the viewing area, the path narrows to 2.8 m so only a few people can walk together. The combination of the roof, wall, and railing direct people’s views to the North-East towards the untouched landscape and lake.

Discover: As a result of the revegetation work in the town, many animals and plant species that once left the area because of the toxicity in the ground and water are now returning. This part of the pathway is opened on both sides so people can easily look down to the ground and discover who is mingling down on the hillside.

Remember: As the pathway loops around so people can return to the main building, they encounter the memorial to the victims of slow violence – asbestos-related diseases. Patients, residents, and those lost in the past will have their names engraved on a tall wall clad with black, reflective granite. The thin slot between the roof and the 7’ wall lets light in while creating a darker, somber setting.

Reflect: Finally, before completing the loop and walking back down, people are invited to sit down, look out and reflect.

At arrival area outside of the hospice on the second level a series of planted areas and cedars that act as a buffer between the hospice and the parking lot. The series of sloping roofs signal the entrance to the building and relate to the sloping topography.

The interior public corridor on the ground floor clinic has a curtain wall that lets patients walk along the perimeter of the building with an amazing view outside while also providing natural light to the interior spaces. There are frequent rest areas in all corridors of the building so patients never have to walk further than 20 m without being able to take a pause and sit.

In a typical resident room, there is custom millwork behind the bed that provides a headboard that is integrated into a system of shelves and cabinets. These are the perfect places for residents to store personal items so that they are easily accessible and can make them feel more at home. This unit can also hide and store necessary medical equipment, so the room can feel more residential. The residents can benefit from ample natural light through the glass door and windows but can also have darkness when needed with a blackout curtain. A range of artificial lighting within the room also helps to suit the needs of the resident at all times of day. A wood slat divider helps to divide the spaces between the bed area, living area, kitchenette, and private washroom. On the exterior, each resident gets their own private balcony. Wood slats similar to those on the interior delineate between each residents’ own balcony space.

On the two levels, the vein of green runs through the building and the spaces overlap. On the ground level, the indoor atrium and geology exhibit are within a double height atrium that lets residents, outpatients, and the community interact. Outside in the cut out, the exposed rock face that resonates with the geology exhibit. This area highlights the history of the region and the asbestos mining as well as the green, healthy future. On the second level, the hospice houses the residents’ personal gardens. If residents so choose and are able, they can take care of plants in this garden. The platform gardening set up enables residents in wheelchairs or with mobility issues to easily experience and reach the plants.

The space for viewing on the outdoor, elevated, fully accessible pathway is opened on the east side providing an amazing view. The memorial is more enclosed to provide a darker, somber space. Names of loved ones are engraved on the dark granite wall that is illuminated from the base.