This thesis project explores the way criminal justice architecture has been impacted by a system that continues to privilege punishment and deterrence over rehabilitation. Deterrence focused policies do very little to address the root causes of crime primarily because they fail to act pro-actively in ways that encourage the upward social and economic mobility of vulnerable community members. Despite this, the Canadian criminal justice system continues to operate in a way that seeks to punish those who commit crimes rather than rehabilitate them, and while this lack of care is expressed in policy it is also visually personified by the architecture produced, as seen below.

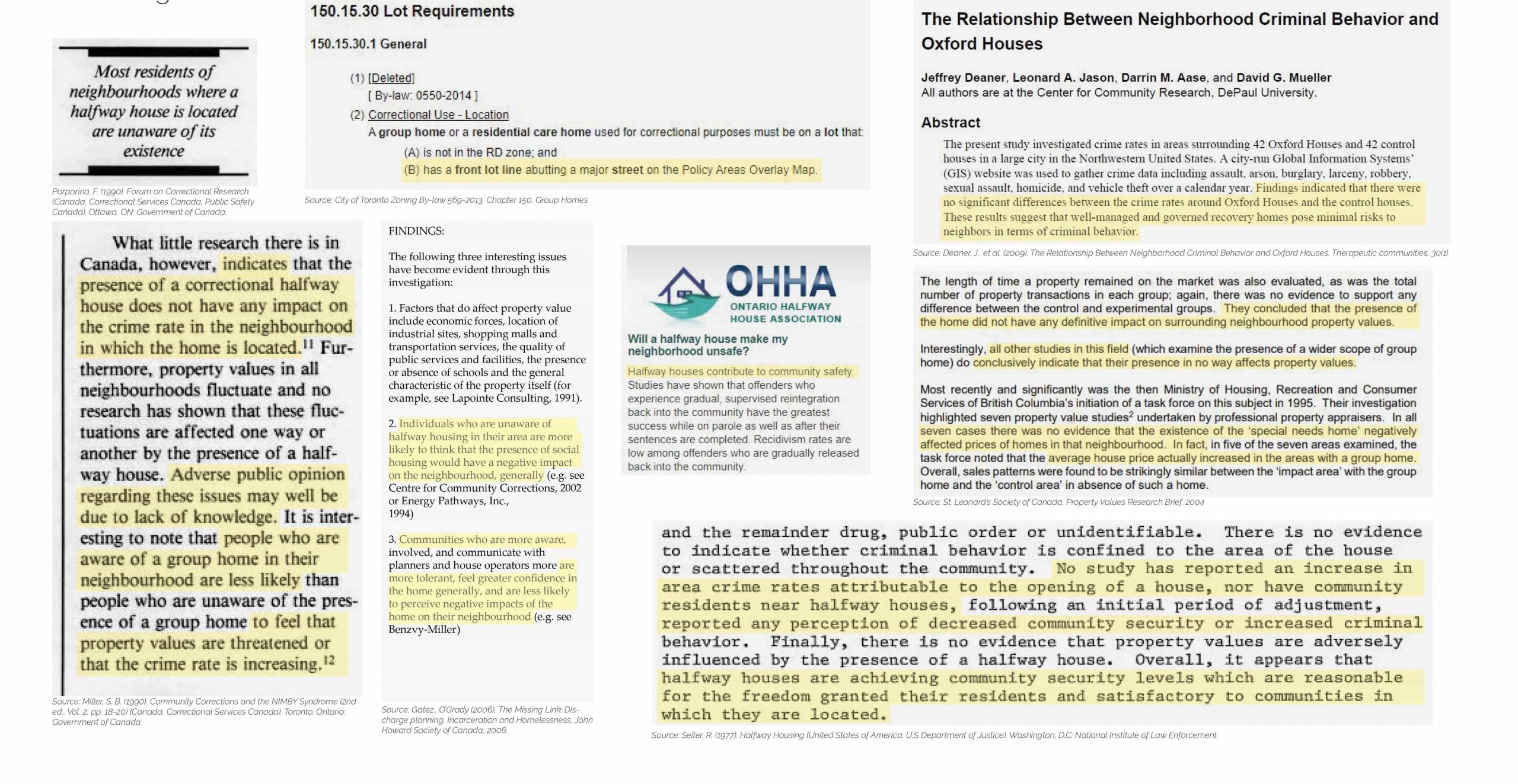

NIMBYism makes it very challenging for Canadians to move past the stigma attached to prison and those who have been subjected to it, as well as Its affiliated infrastructure, like halfway housing or shelters.

This makes it challenging for Governments to secure funding that could contribute to a more rehabilitative infrastructure even if they did want to.

Presented here are the key findings that should dispel concerns raised by NIMBY supports and prove that halfway houses do not: devalue real-estate, increase crime, or breed criminals.

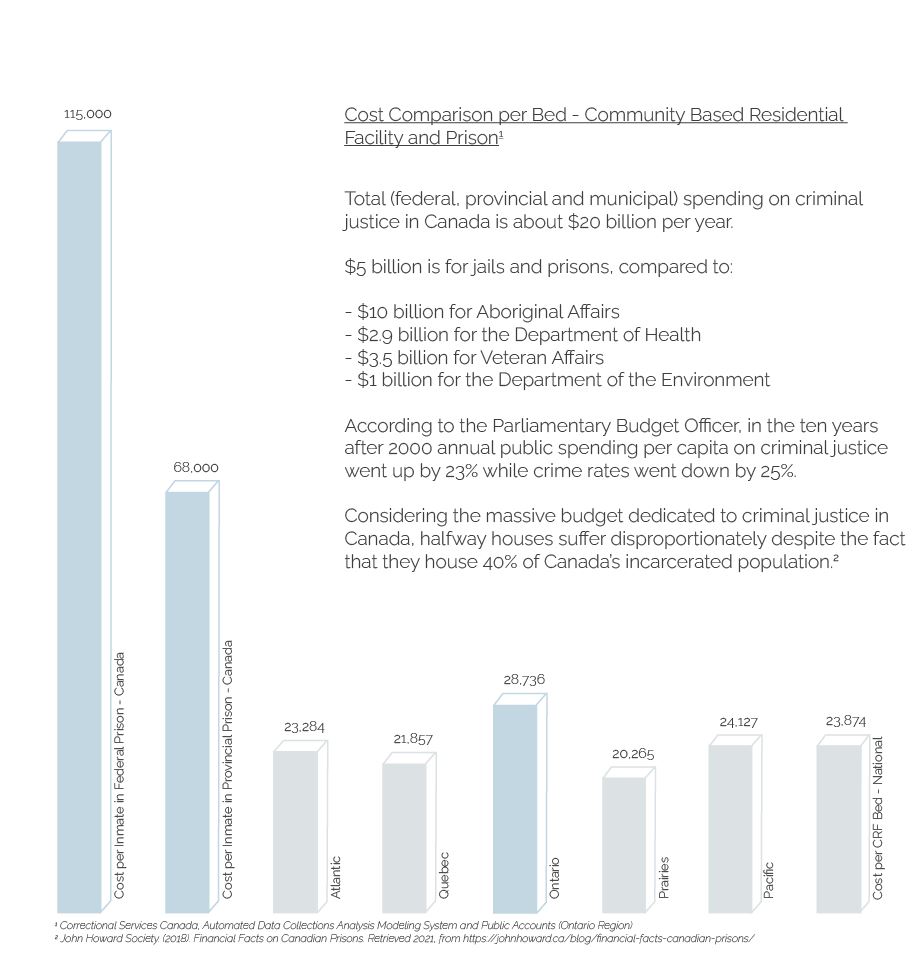

Canadians spend 20 billion dollars on criminal justice a year and 5 billion on housing people in jails alone. Crime rates have been steadily decreasing over time and yet spending on criminal justice continues to increase exponentially. It costs 115,000$ to house one person in federal prison for a year compared to 28,000$ housing someone in a halfway house for a year.

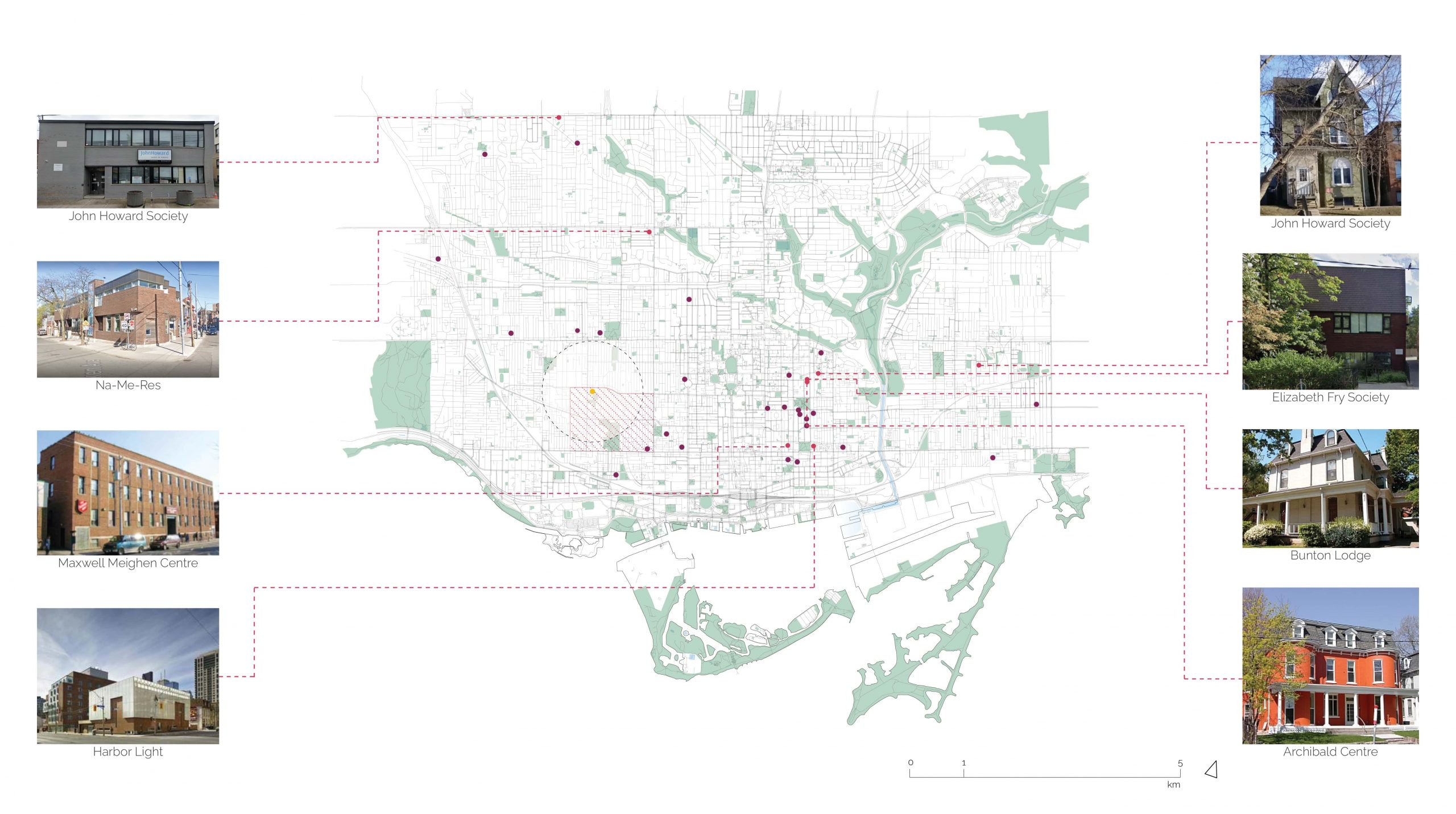

Of the roughly 12,000 people being held in prison right now 3000 of them are considered to be low risk and could be serving their sentences in a halfway house under community supervision. There are 8 halfway houses in Toronto and 43 in Ontario.. They hold 40% of our incarcerated population and yet are significantly neglected and in need of repair despite the important role they serve.

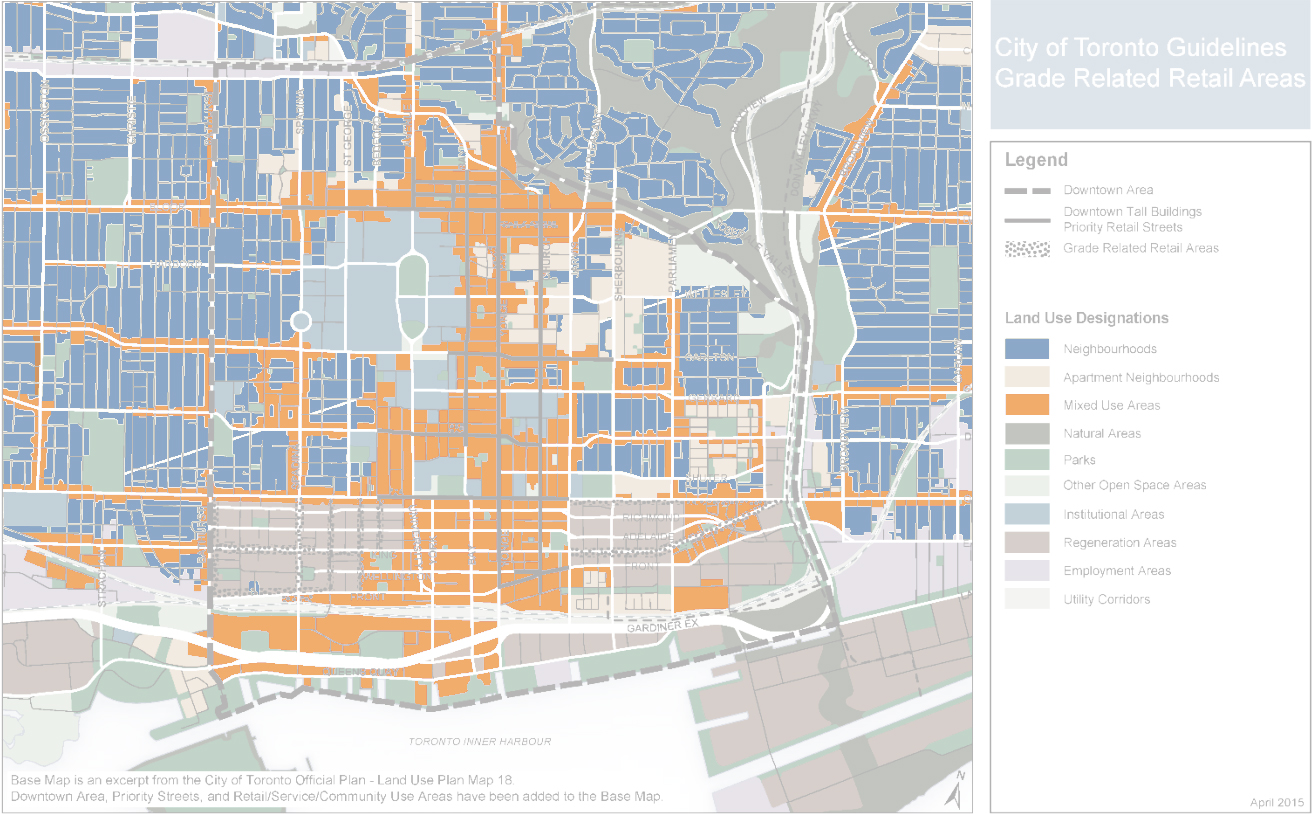

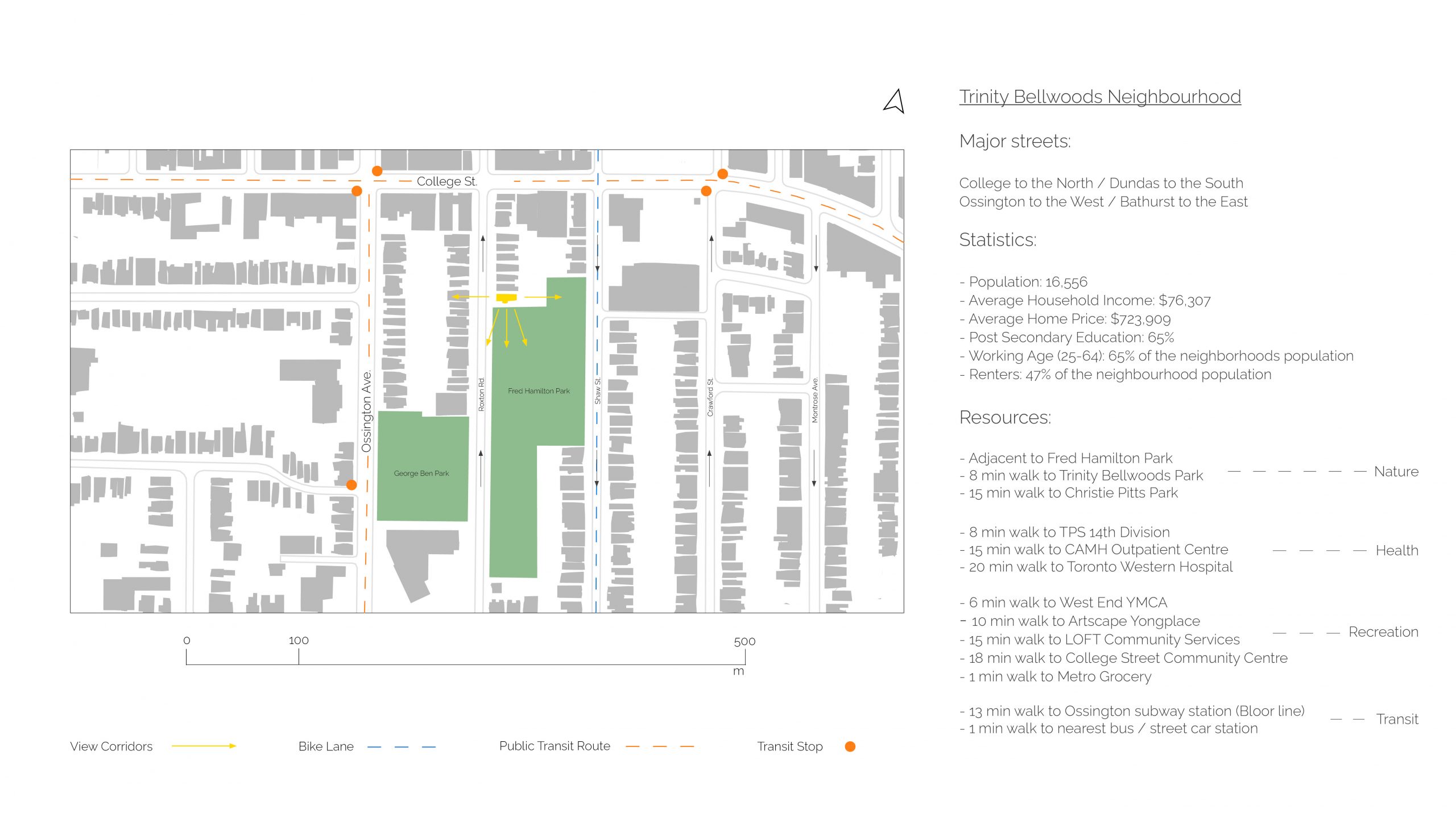

The City of Toronto identifies neighborhoods as an amalgamation of smaller scale communities defined by man made boundaries, typically major streets, that can consist of residential uses in lower scale buildings such as, detached houses, semi-detached houses, duplexes, triplexes, townhouses, as well as interspersed and walk-up apartments no taller than 4 stories.

Current zoning bylaws restrict halfway housing developments to major streets. This means more residential streets cannot host these community based residential facilities. The problem with restricting these types of developments to major streets is that they usually create neighborhood boundaries and foster residential communities within them.

So, while major streets do host some residences, are culturally rich and hold valuable social resources, they are typically reserved for mixed use developments making them more noisy, overwhelming and disorienting especially for people transitioning from prison.

By restricting halfway housing to major streets, it immediately isolates these developments as well as the house residents from becoming integrated in established community networks. Most importantly continuing to place halfway houses on periphery streets and not in communities suggests to community members that these institutions are in some way threatening while simultaneously suggesting to the house residents that they are perceived as threatening, making it extremely challenging to dissociate from an assigned criminal identity.

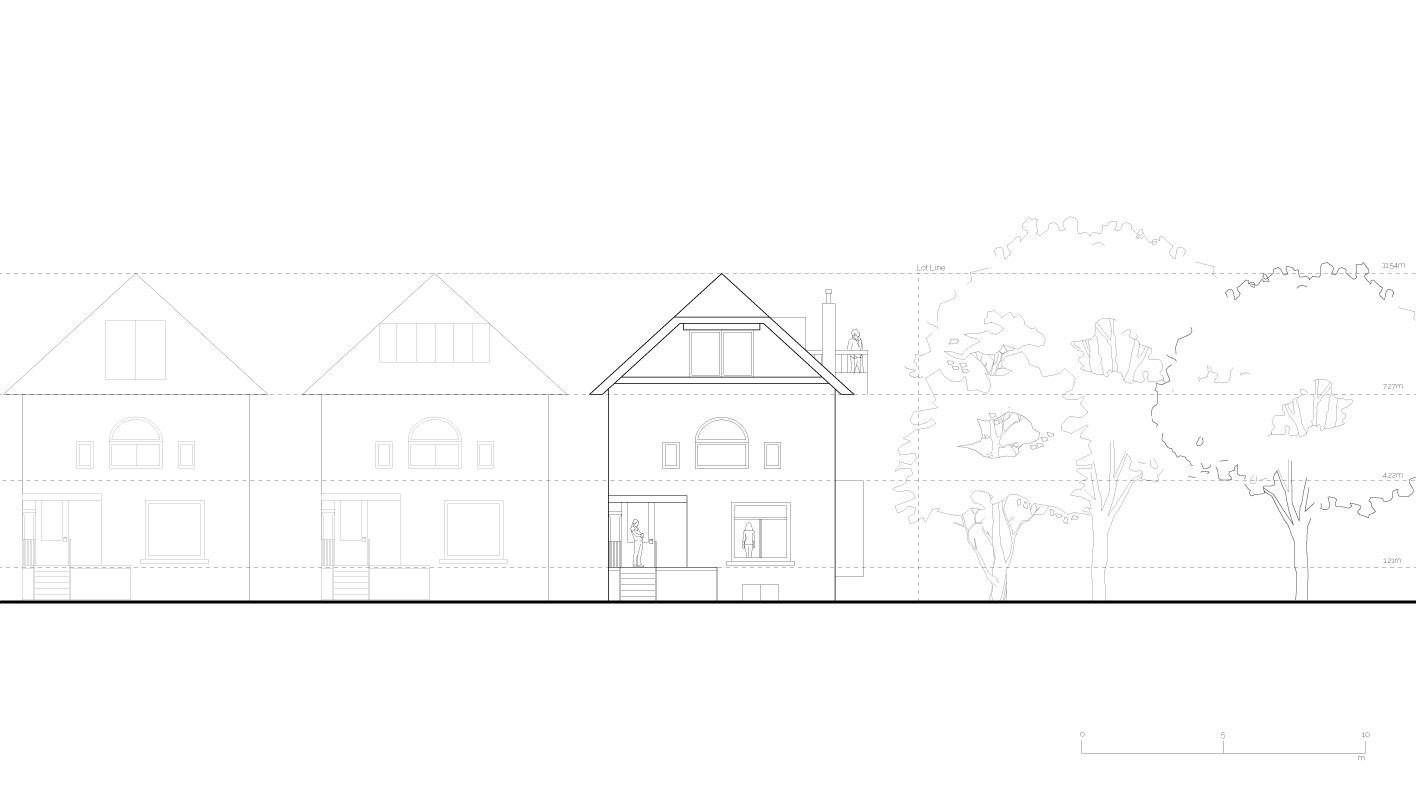

While no formal document exists detailing site selection criteria for halfway houses I have compiled some information that helped me choose my site just south of college on Roxton Road, a residential street, in the Trinity Bellwoods Neighborhood

It has been suggested that halfway houses have had more positive community receptions in neighborhoods that would be more willing ‘to give them a chance.’

Characteristics of these neighborhoods include:

– middle or working class neighborhoods

– neighborhoods with cultural and ethnic diversity, and various housing typologies

In addition to those general qualifiers, the site MUST:

– have direct access to public transit

– sightlines to nature

– access to natural light

– be in close proximity to social, recreational and heath care services which would not only benefit the house residents but make facilitating connections between these resources and the house itself easier

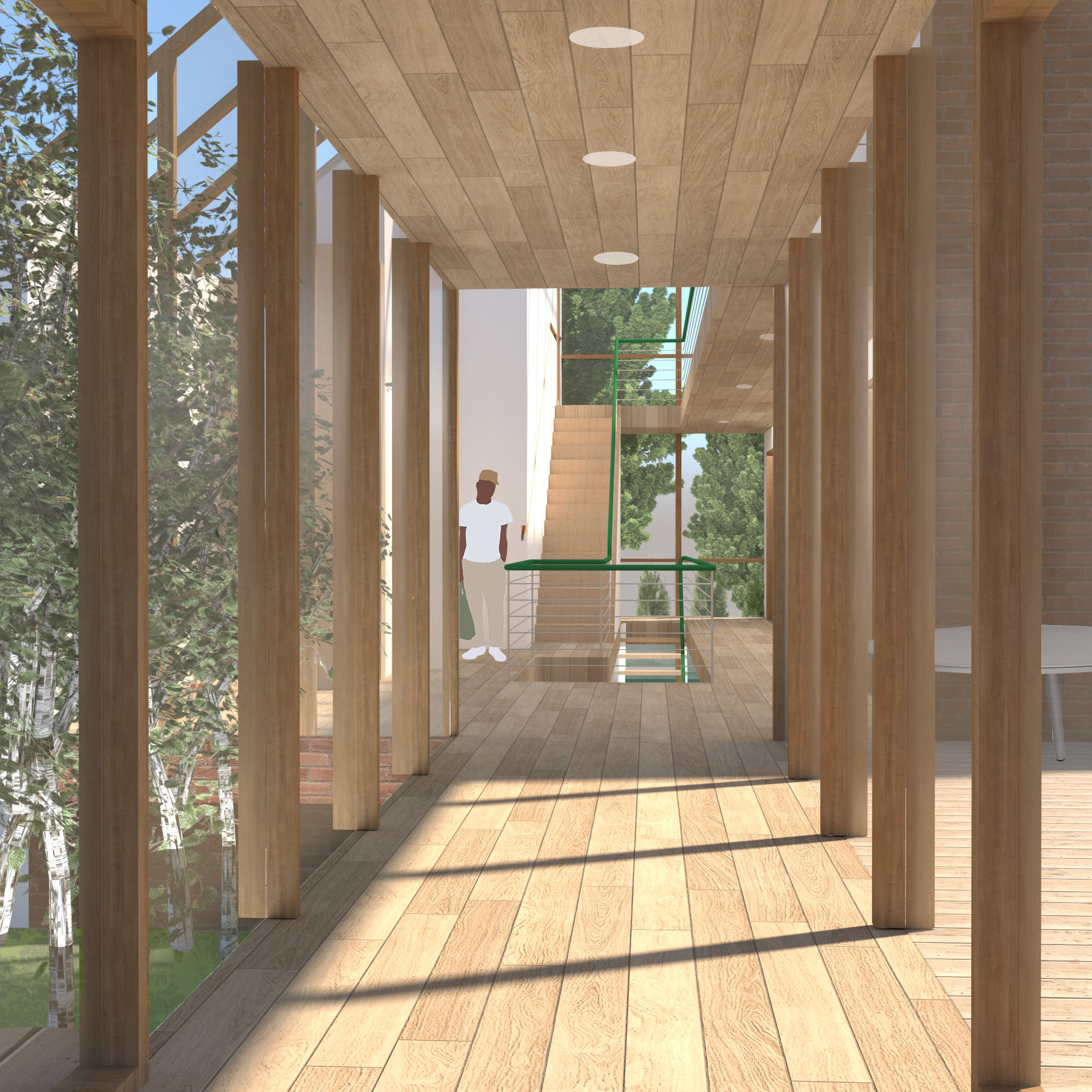

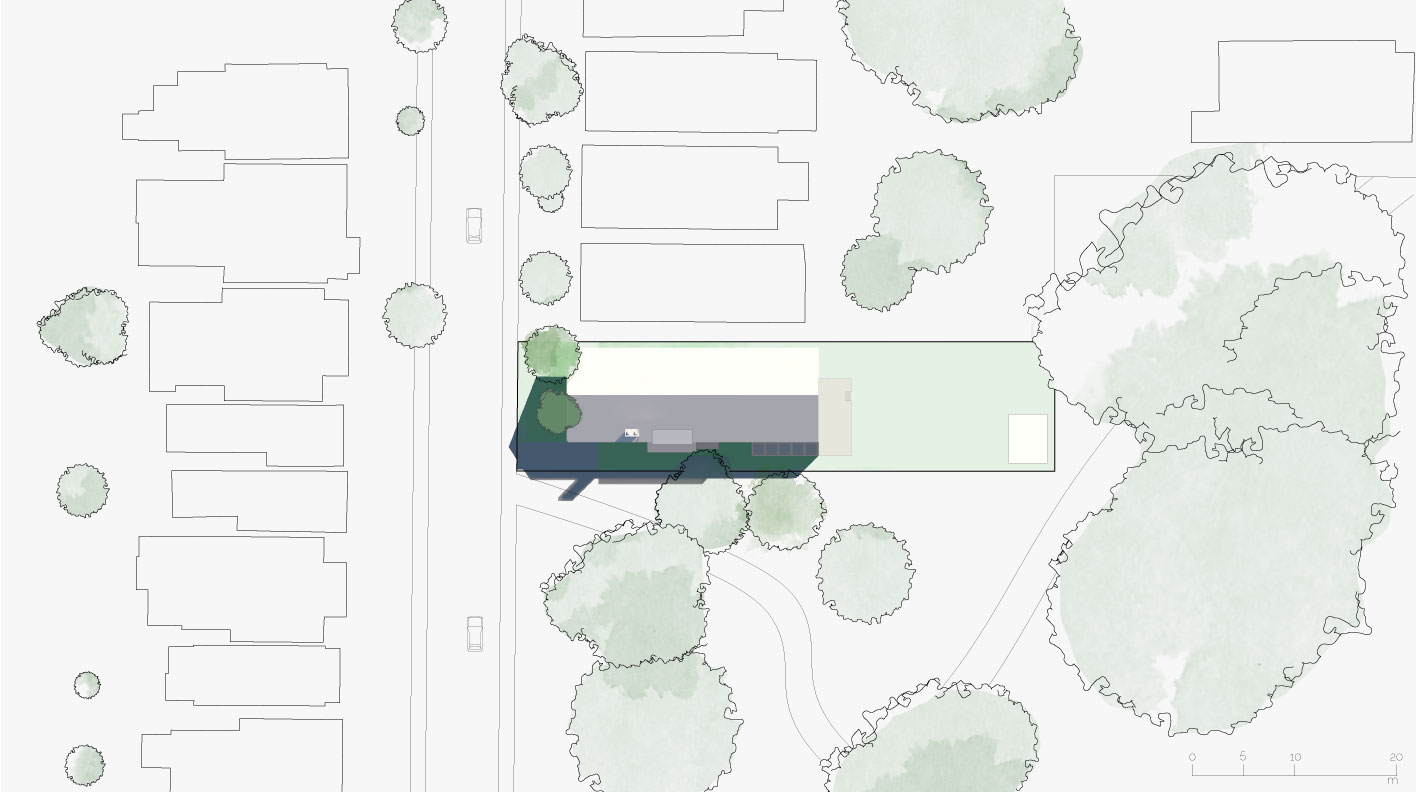

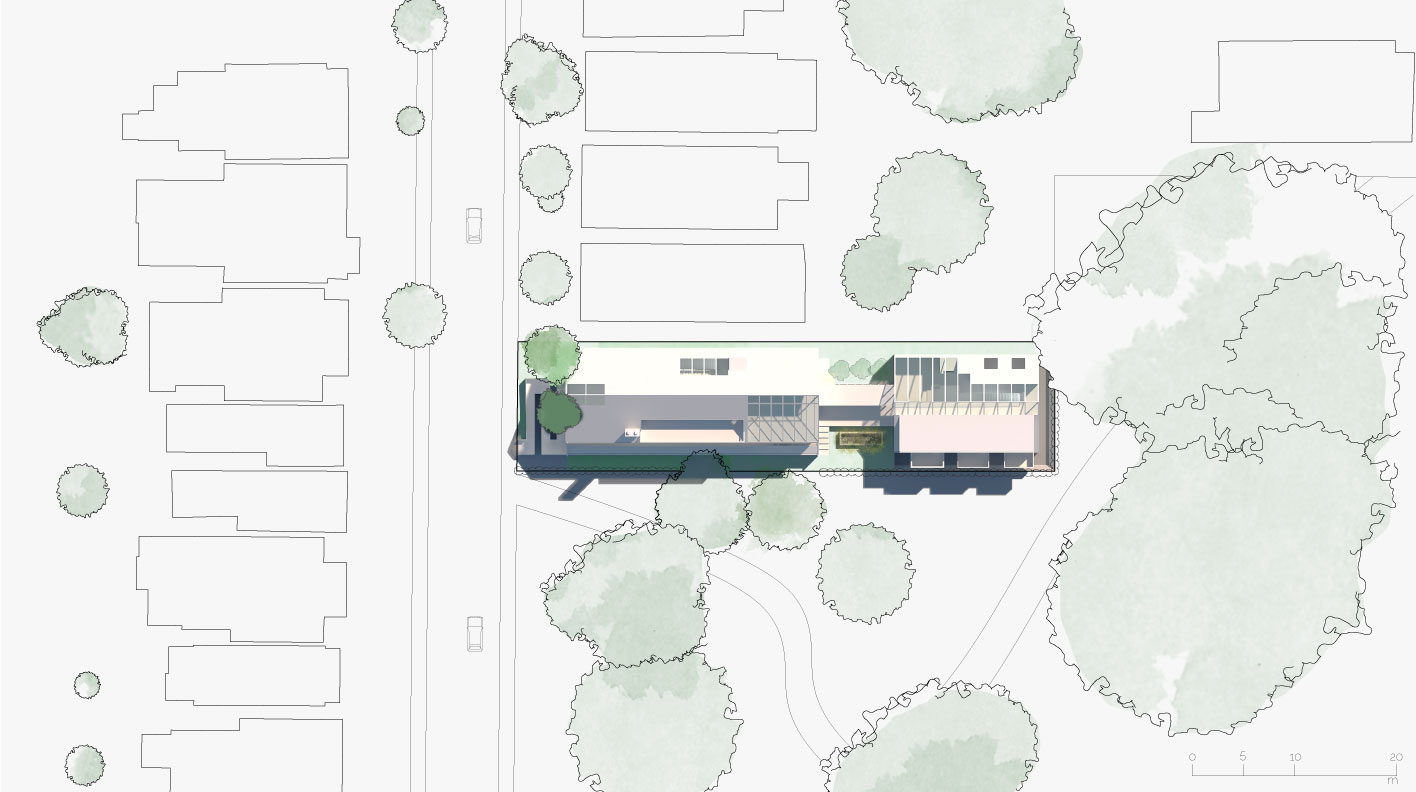

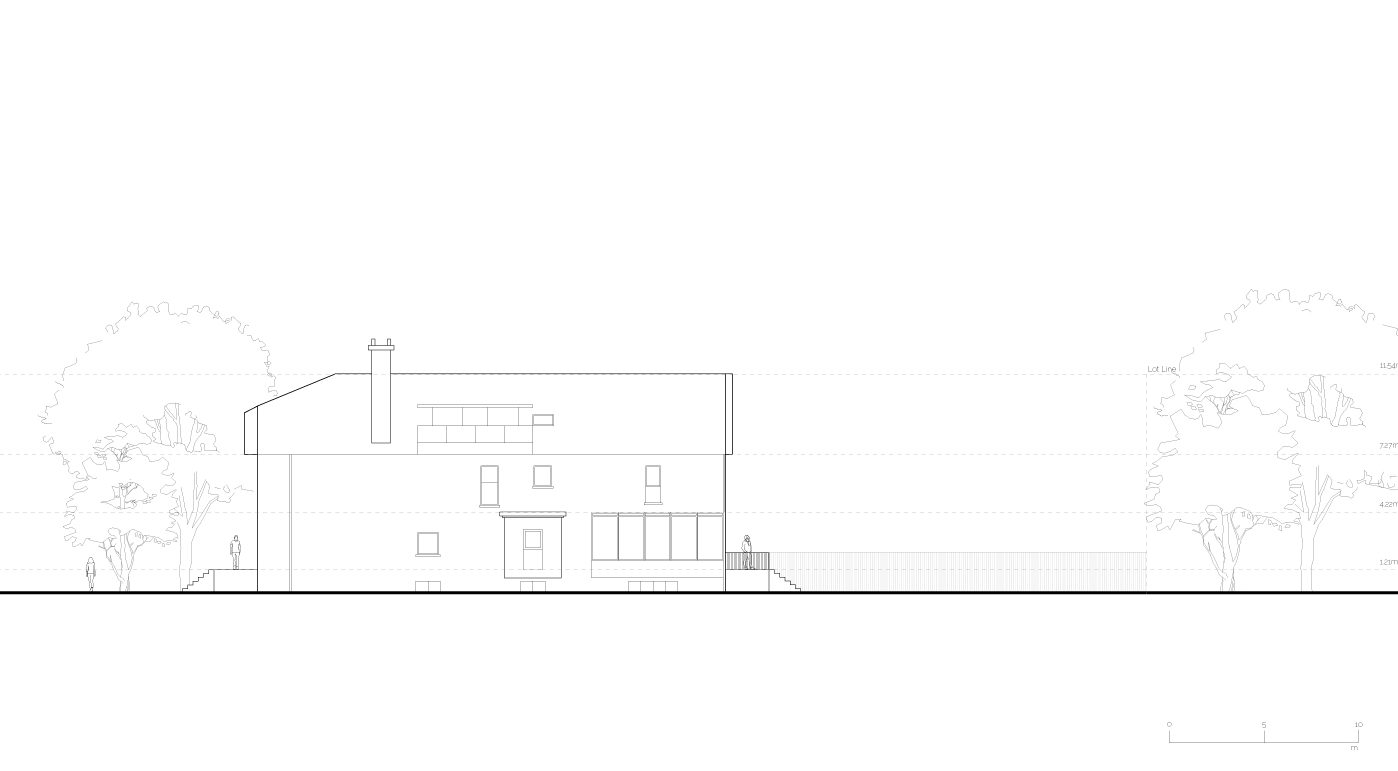

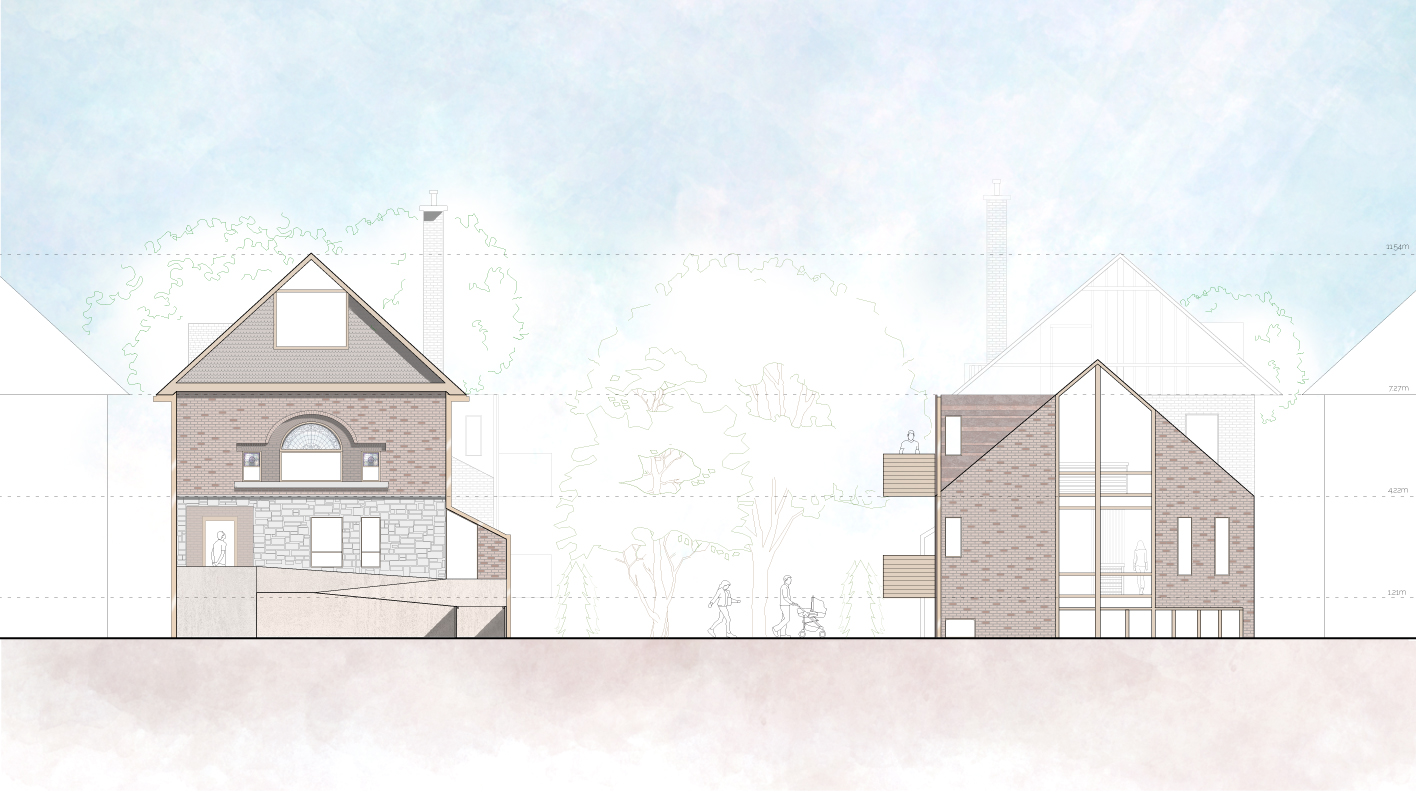

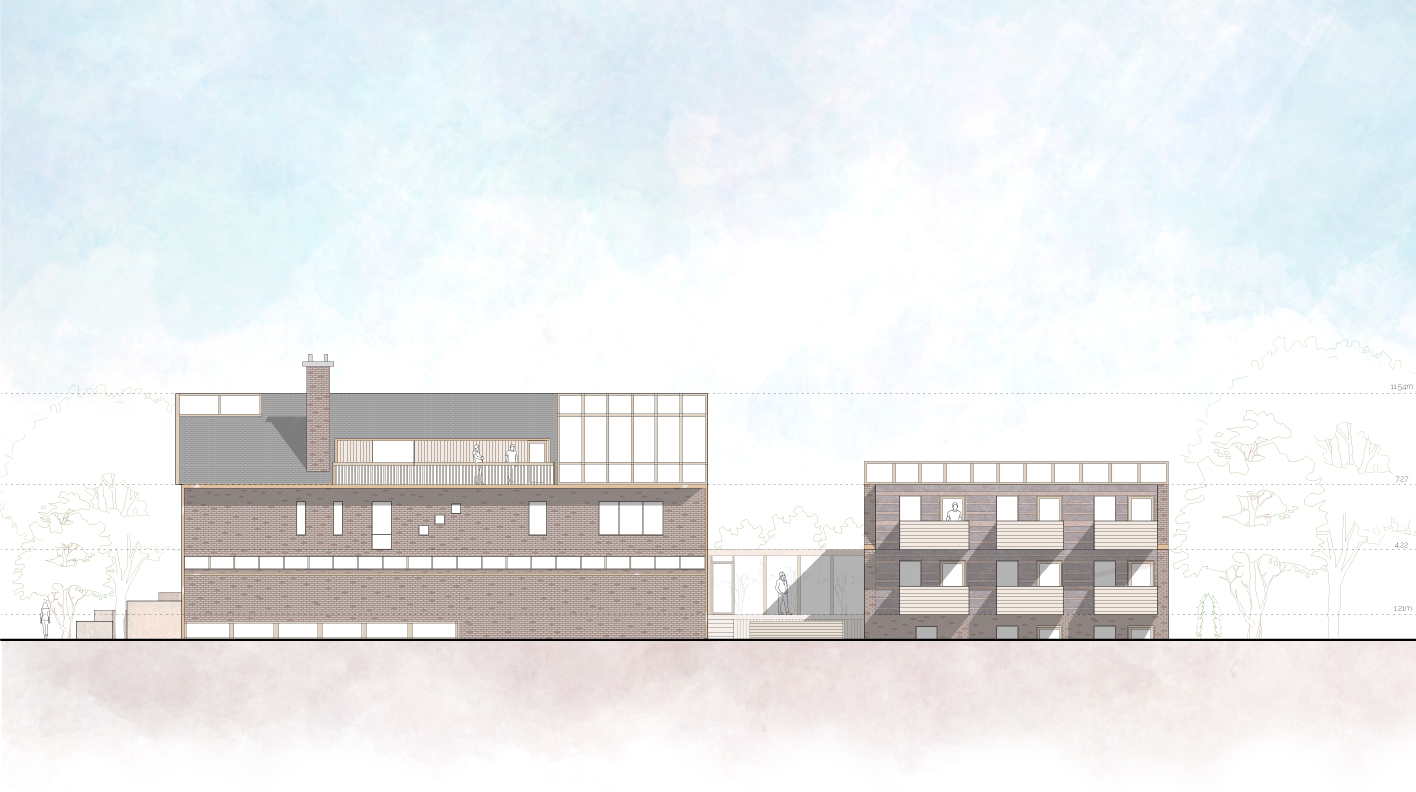

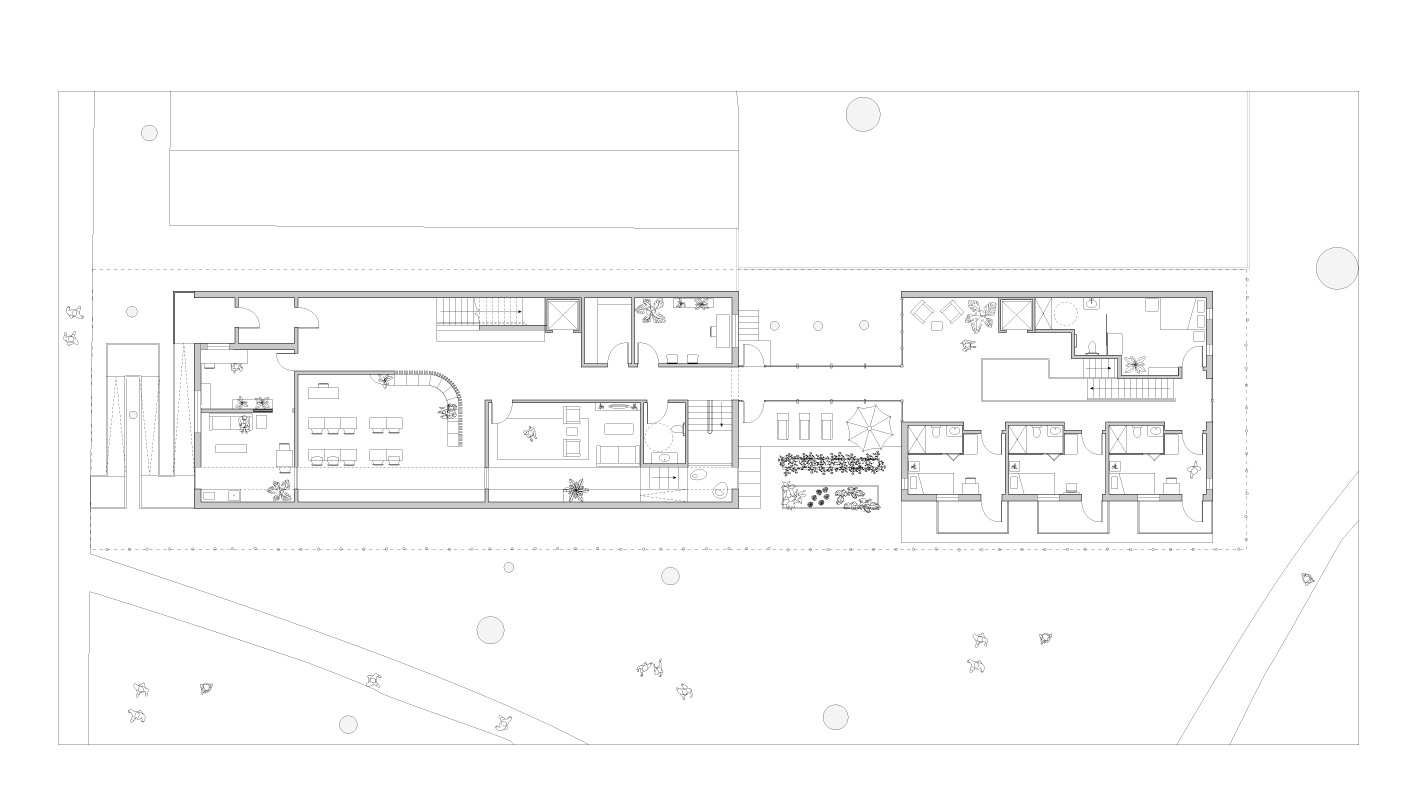

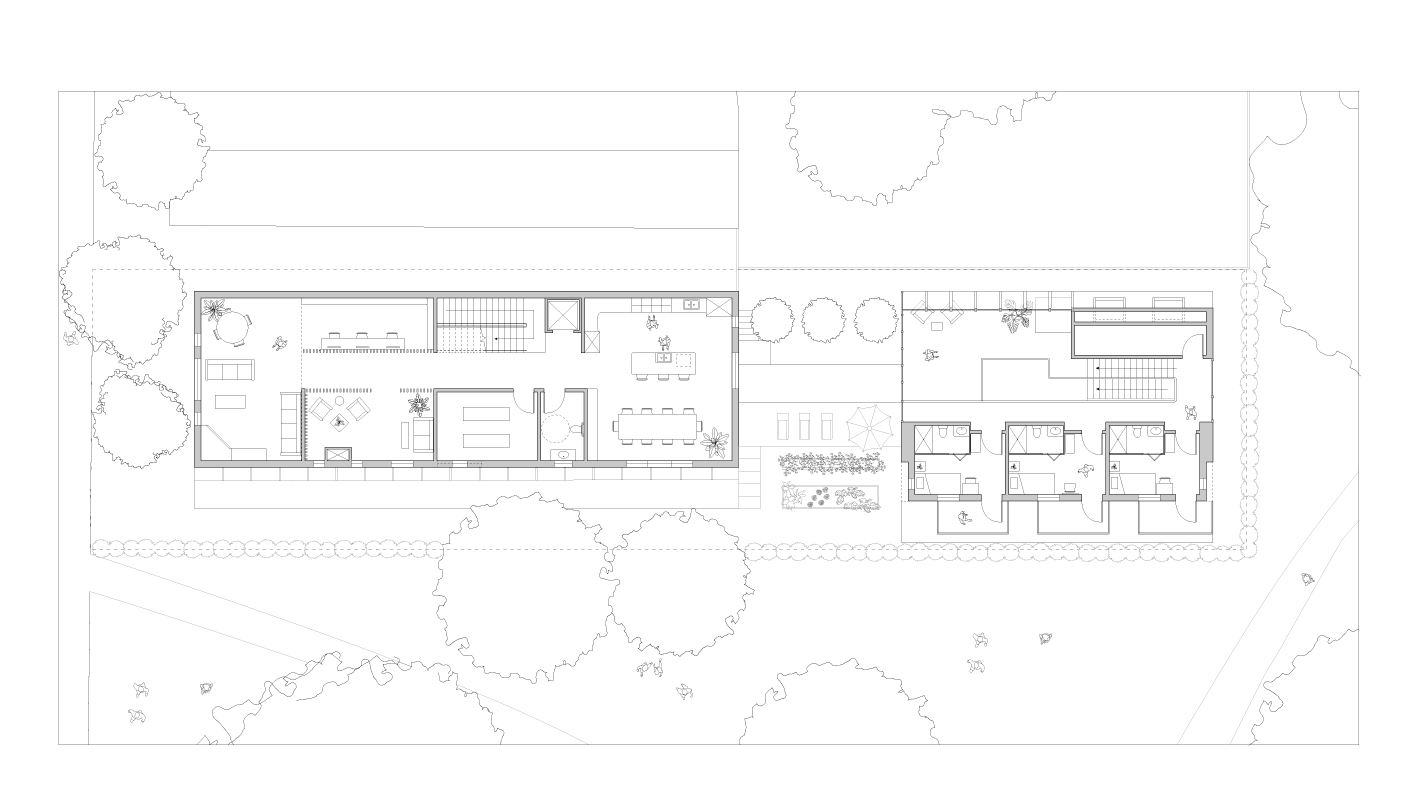

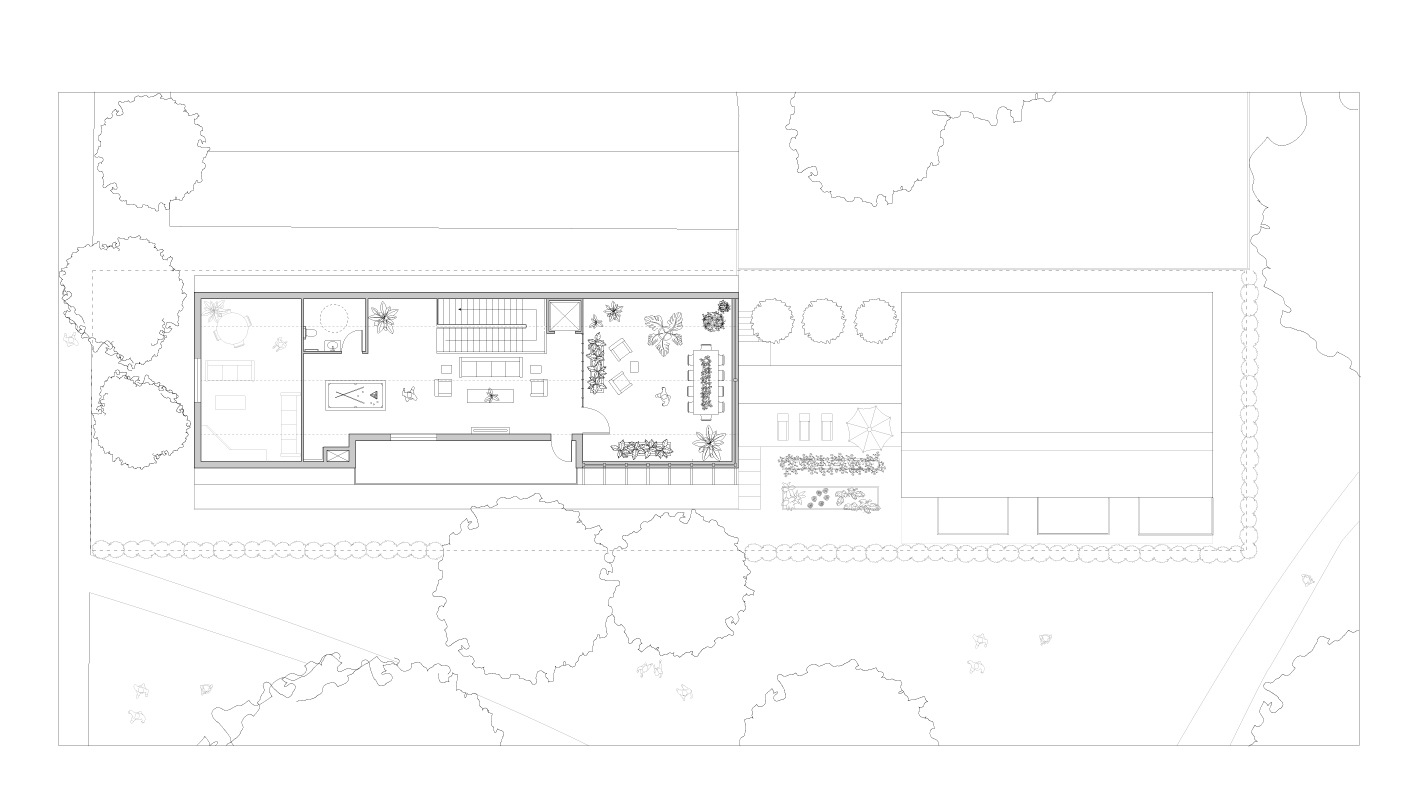

Major changes involve making accommodations to house 10 male permanent residents, 2 staff on 8 hour shifts and 1 in house social worker. Permanent residents will stay for a minimum period of 6 months and will be between the ages of 25 and 55. The existing house will be renovated to draw on principles of CPTED and salutogenic design. Towards the rear of the lot a new portion of the house will be constructed, connected to the old via an enclosed path, where the residents will sleep enveloped by the surrounding trees.

Certain programmatic additions have been made to ensure that the house functions and feels like a typical residence while improving conditions and comfort for staff, residents and visitors. Some additions include a dedicated staff breakroom, a social workers office, a family visitation room, multipurpose room, single bedrooms with private bathrooms, a workshop, two recreation rooms, a fitness room and spiritual room. Significant consideration was given to emphasizing normalcy in daily operation while creating opportunities for autonomy and social interaction.

These sections begin to show the interior qualities of the living spaces, with careful attention paid to natural material selection paired with a simple colour pallet. Green is used on the interior because of its direct association with nature and stress reducing qualities. The basement of the addition is dug out to allow out door access but also usable, well lit interior space that increases the capacity of the sleeping quarters to 10 residents.