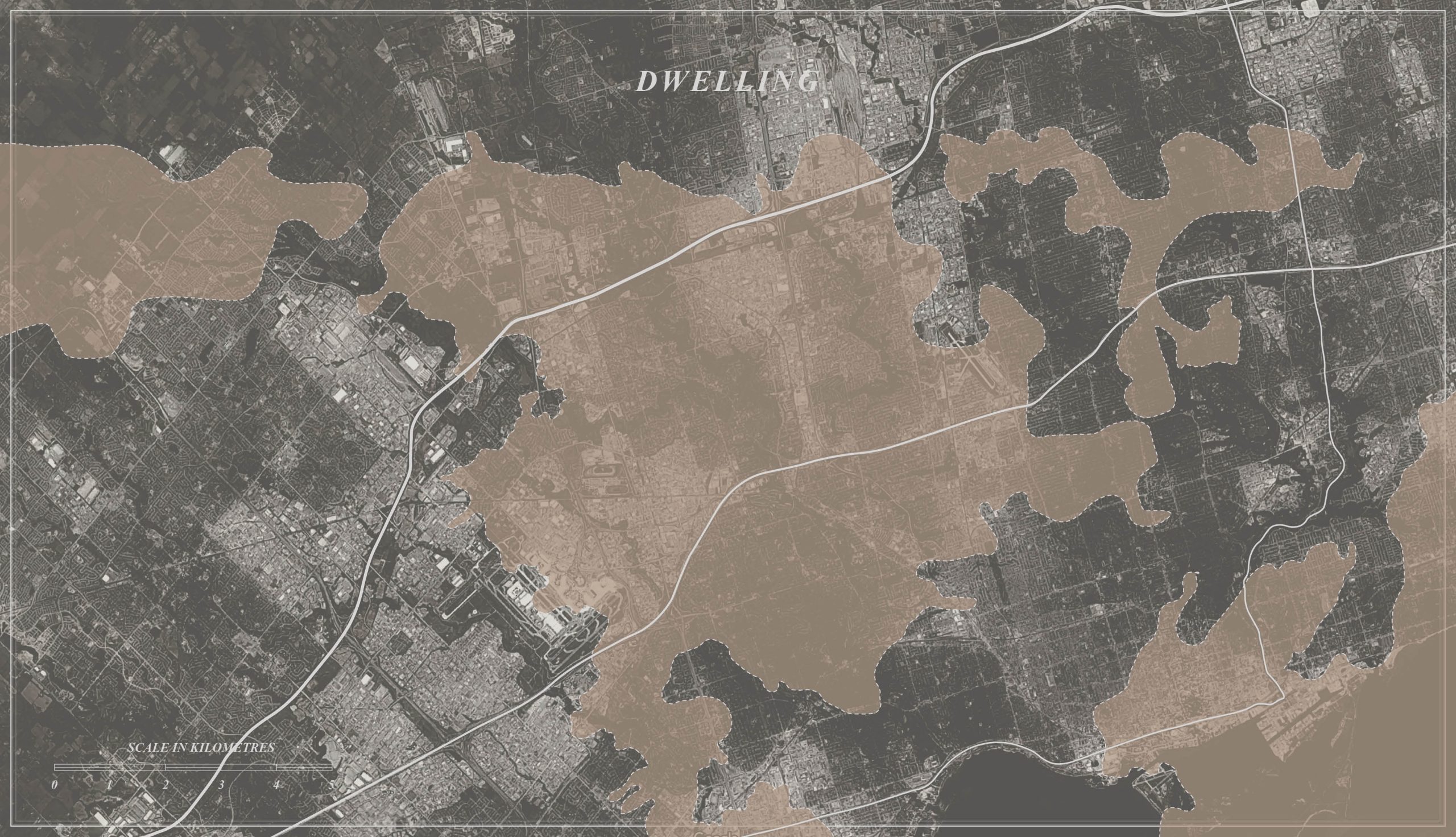

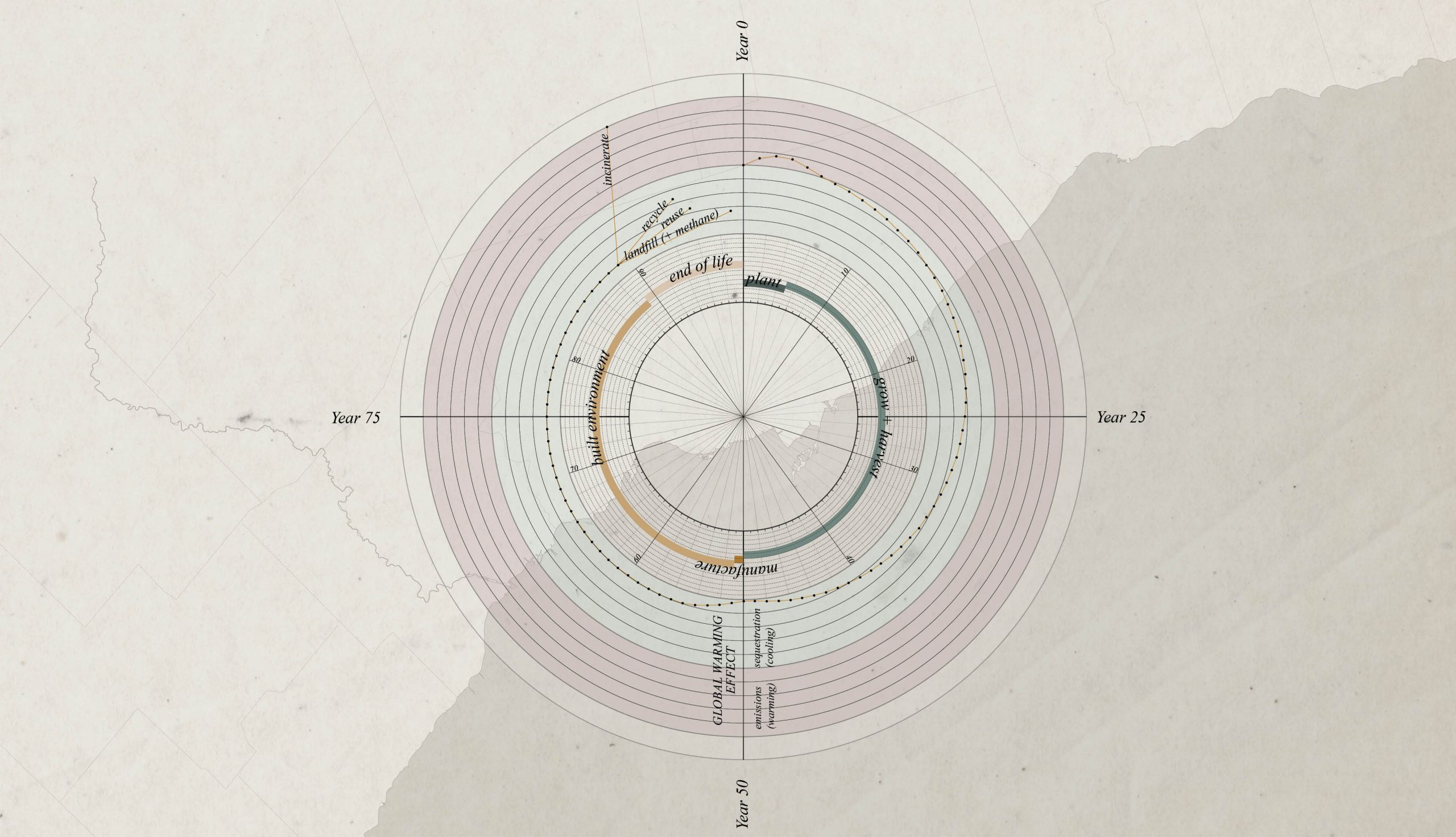

How can the growth of the forest be the mechanism that allows the GTHA to rebuild itself? This thesis proposes an alternative way to grow the city — one parallel with the temporal rhythms of the ever-changing, dynamic forest. It explores the concept of a self-sufficient carbon cycle: growing, harvesting, processing, and rebuilding. It illustrates how we might surrender to wood’s heterogeneity, uniqueness, and intricacies, where a branch’s dimensions dictate design, and where the volume of built elements are proportional to the species available. It offers a reinterpretation of the use, value, and processes of the forest — not as an unlimited resource to extract, but as part of a greater ecological and urban metabolism.

Bird's Eye View of Toronto, Owen Staples, 1813.

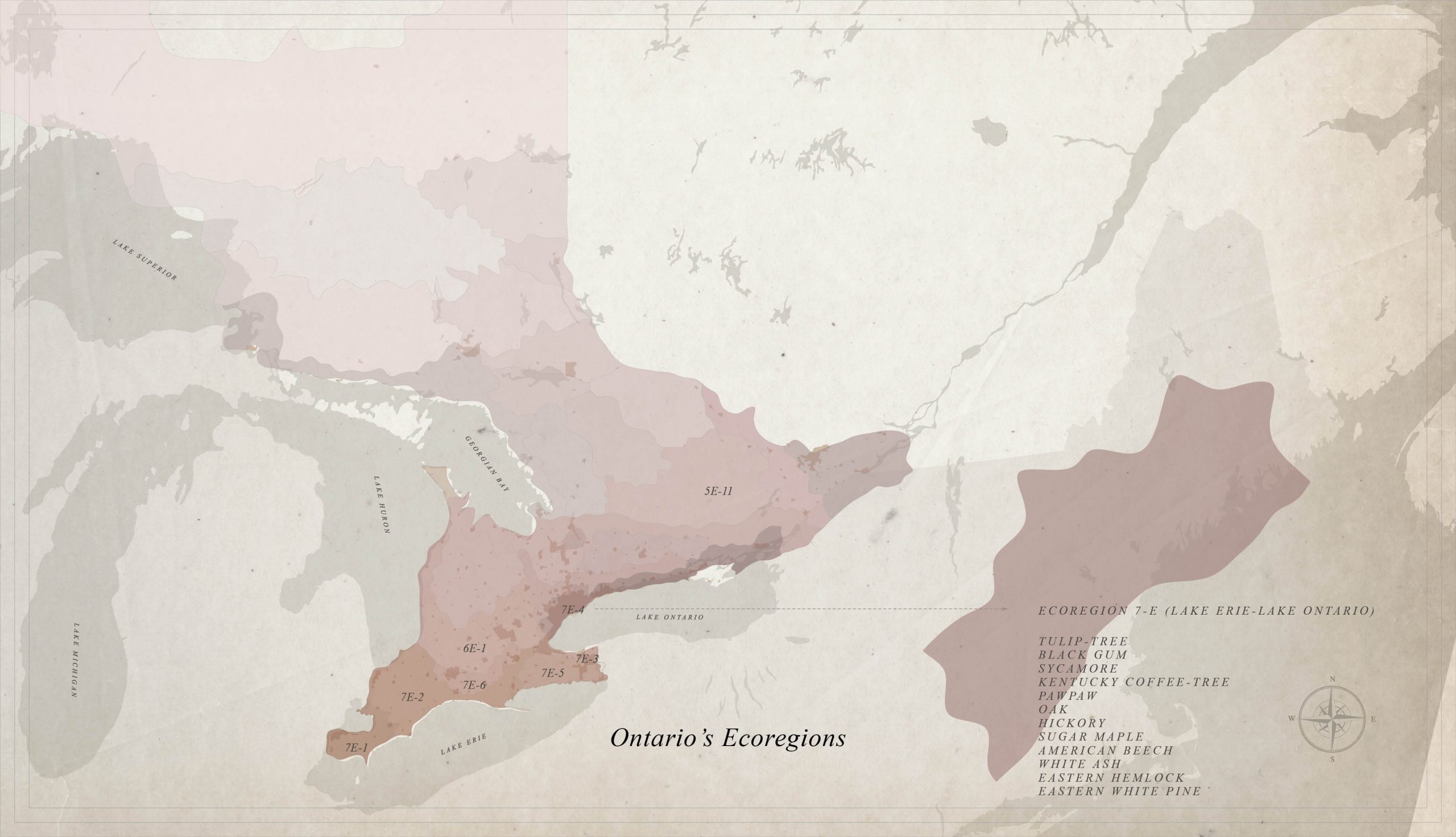

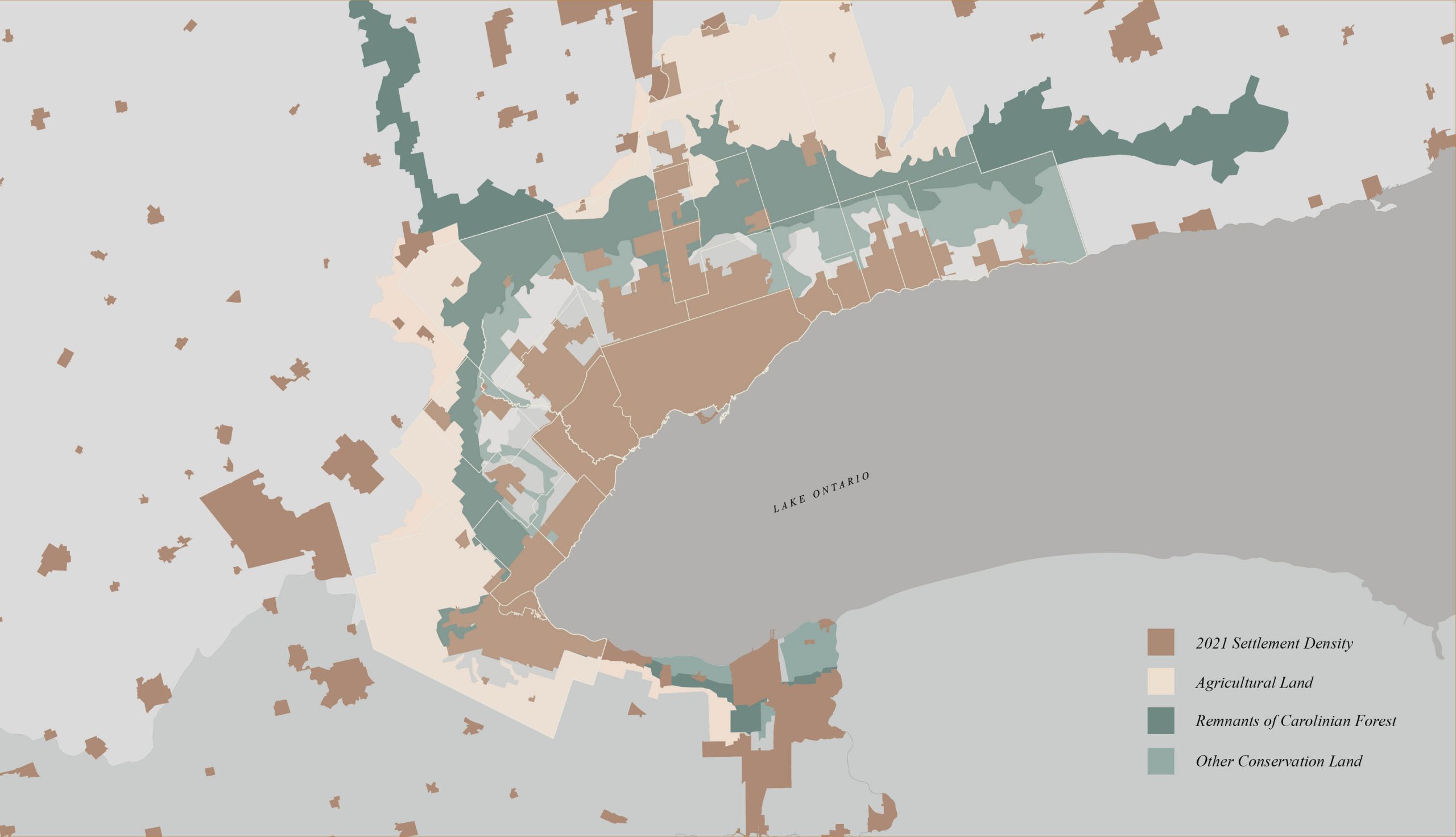

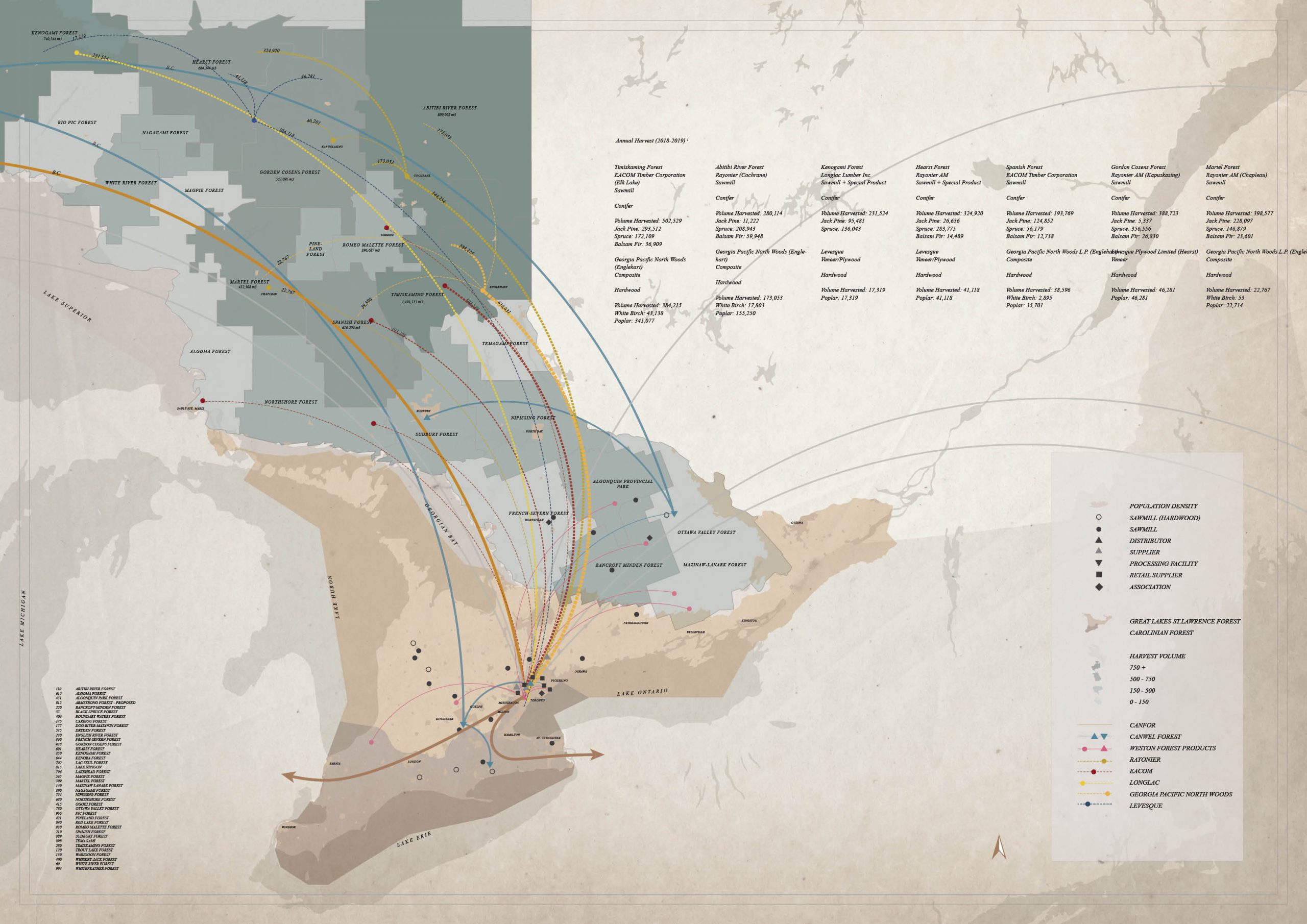

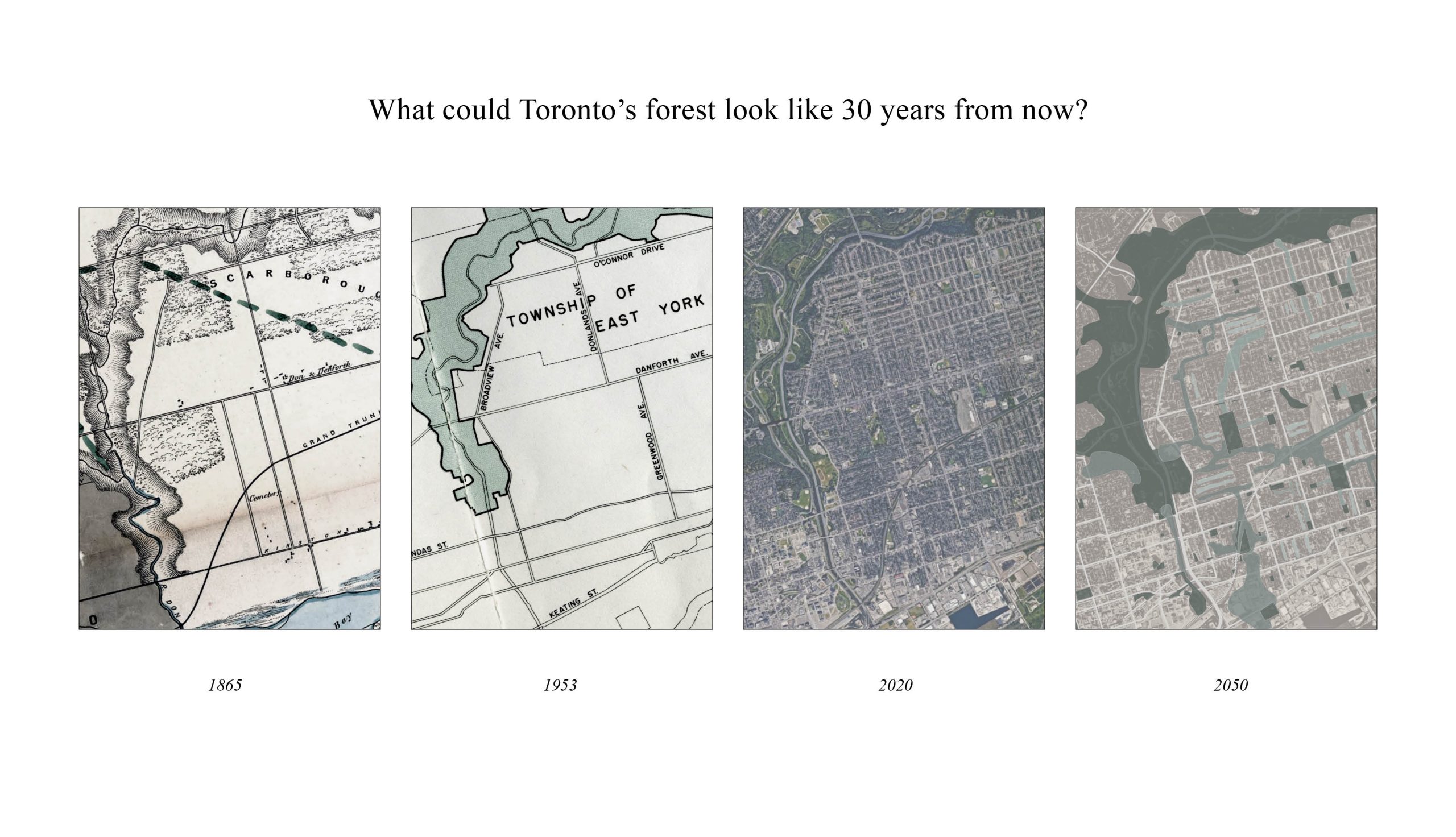

Southern Ontario was once entirely covered in rich, diverse, heterogeneous Carolinian forest, dense with hemlock, beech, oak, ash, and pine. By 1910, only 10% of the original forests remained. Toronto is cut from a hardwood forest – very different from contemporary practices of sourcing coniferous species from across Canada. For centuries, we’ve manipulated forested landscapes to meet dwelling demands in largely unconsidered landscapes. Research on the history of Ontario’s forest, material provenance of wood, indecipherable supply chains and Toronto’s residential housing uncovered a complex set of relationships under which the province grew and expanded itself.

A comparison of Toronto's settlement density between 1883 and 2021.

A map illustrating the complex flow and movement within Ontario’s timber supply chain.

The thesis began with a question,“what is the relationship between the distant, invisible environments where raw materials originate and the urban, built environments in which they are found?” Delving into the history of timber in Ontario reveals a complex past and while the forest edge continues to recede farther and farther from the city limits, forestry is relegated to the periphery. This approach has led us astray, as we are increasingly disconnected from the labour, ecology, and processes required to transform a tree into lumber. How might we remedy the separation of urban and natural cycles, bringing awareness and being in tune with the rhythms of the forest – planting, harvesting and rebuilding?

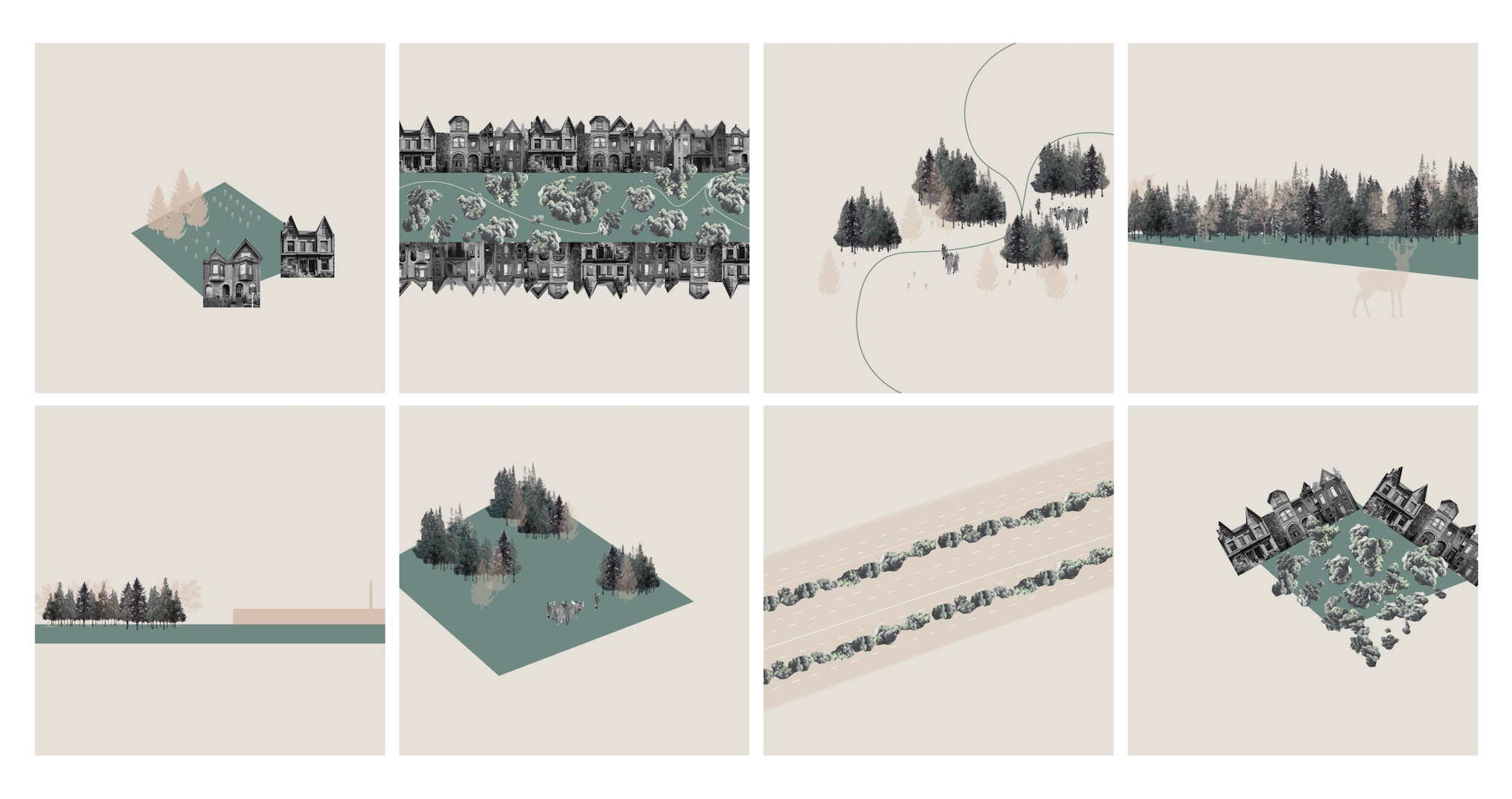

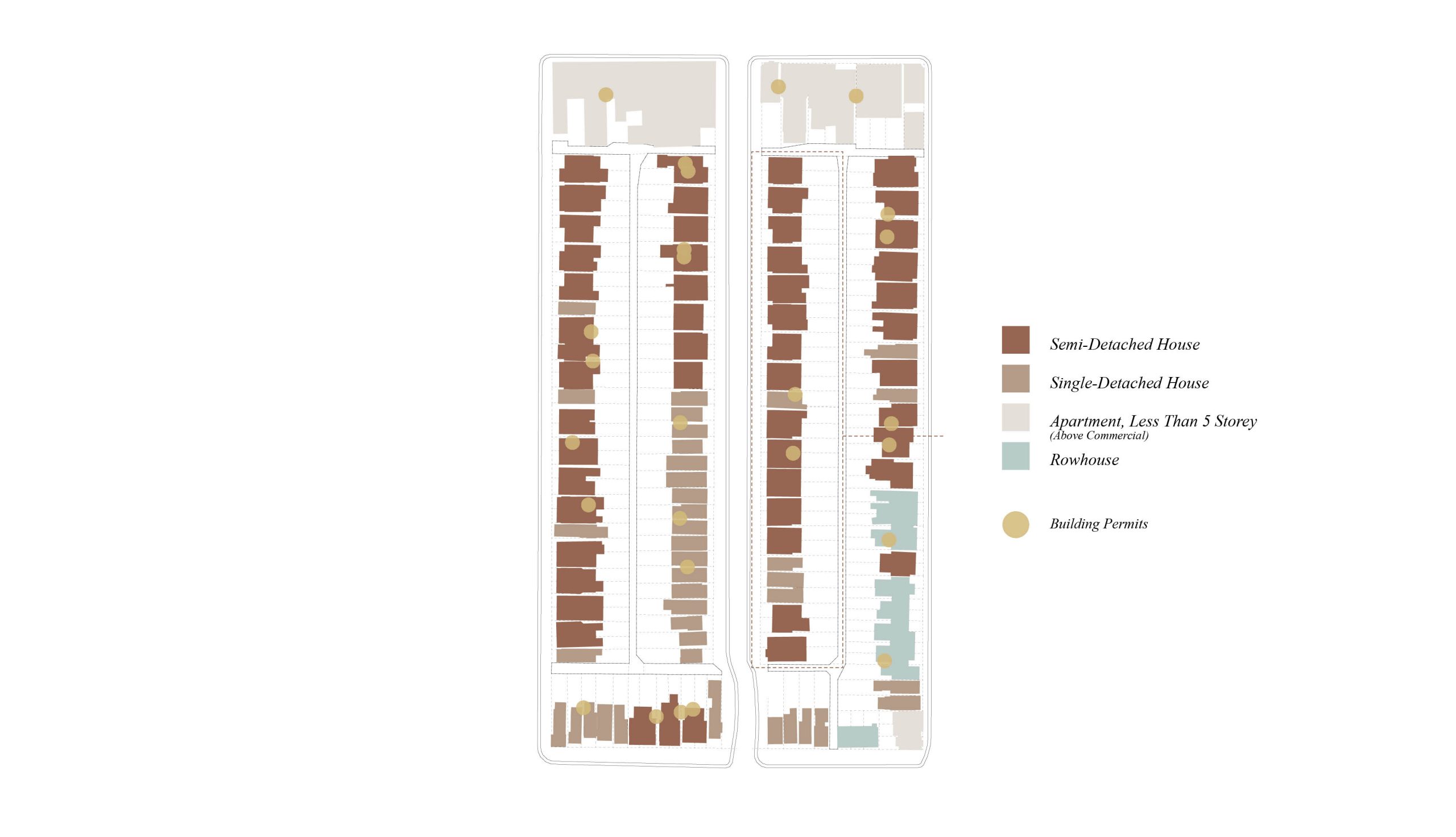

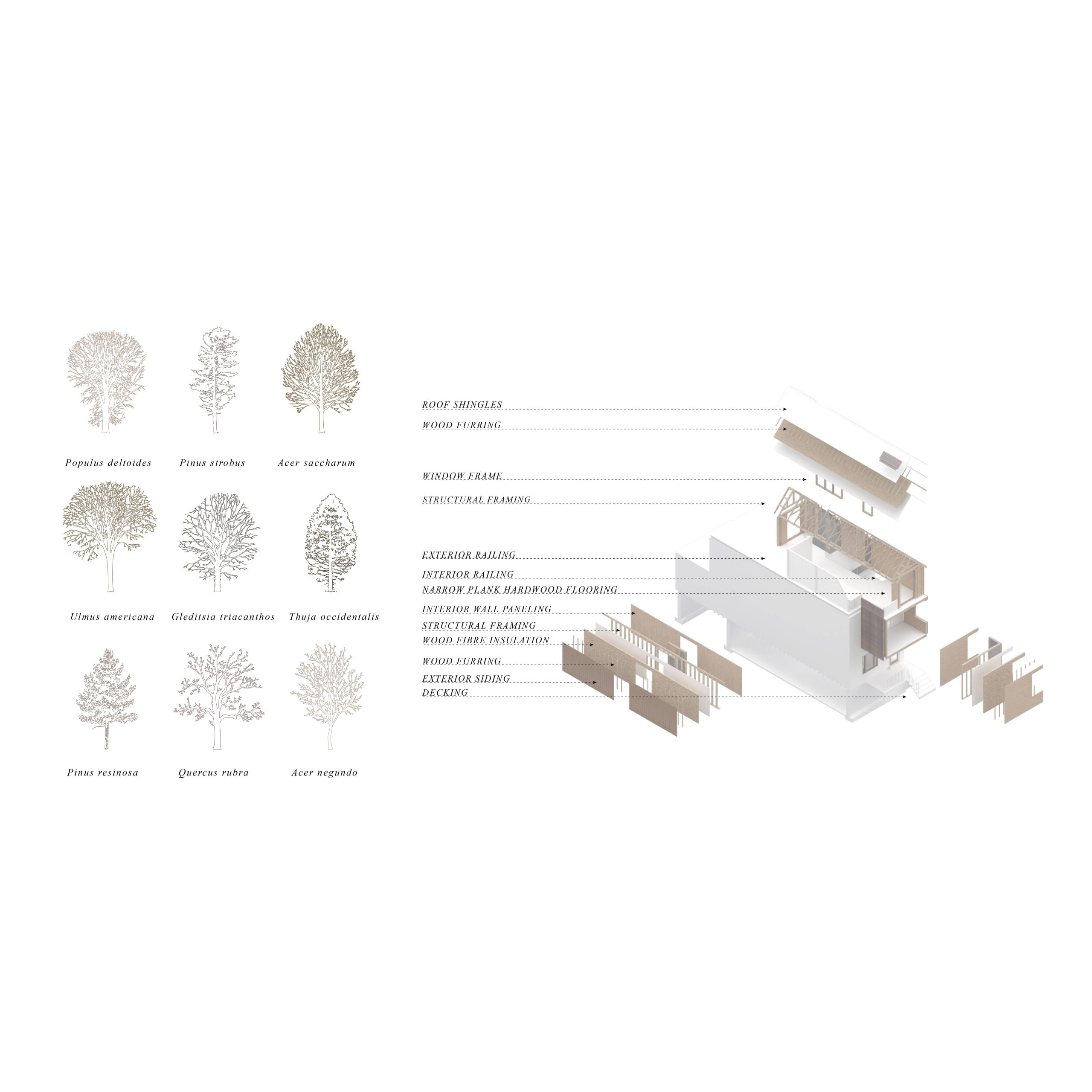

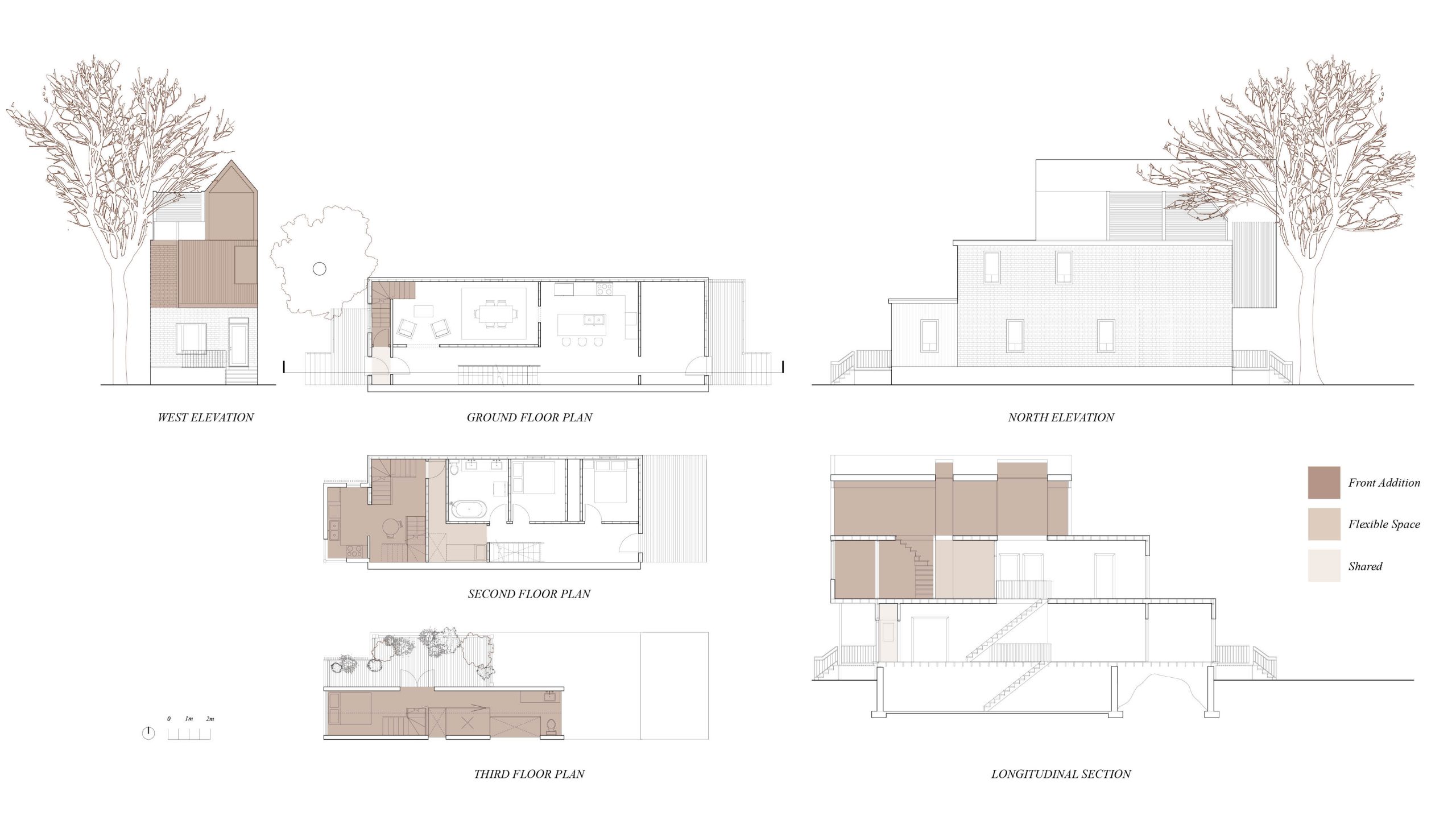

Reforest to Rebuild illustrates a speculative future of an urban neighbourhood that evolves to address density needs and, in turn, responds to related social concerns, improves our well-being by reforesting our landscape, and shifts our reliance from high embodied carbon materials to low embodied carbon materials. It addresses density via introducing multiple-unit housing within a neighbourhood like Leslieville through a new approach: the front addition. Adapting and metabolizing the existing structure of Toronto’s semi-detached typology gently increases density and adds secondary addresses, solely utilizing locally harvested timber. An analysis of existing zoning and by-laws reveals that simple amendments would profoundly address our city’s missing middle concerns. It delves into the policy frameworks while also identifying specific design guidelines that engage embodied carbon. It illustrates a future tied to slow growth.

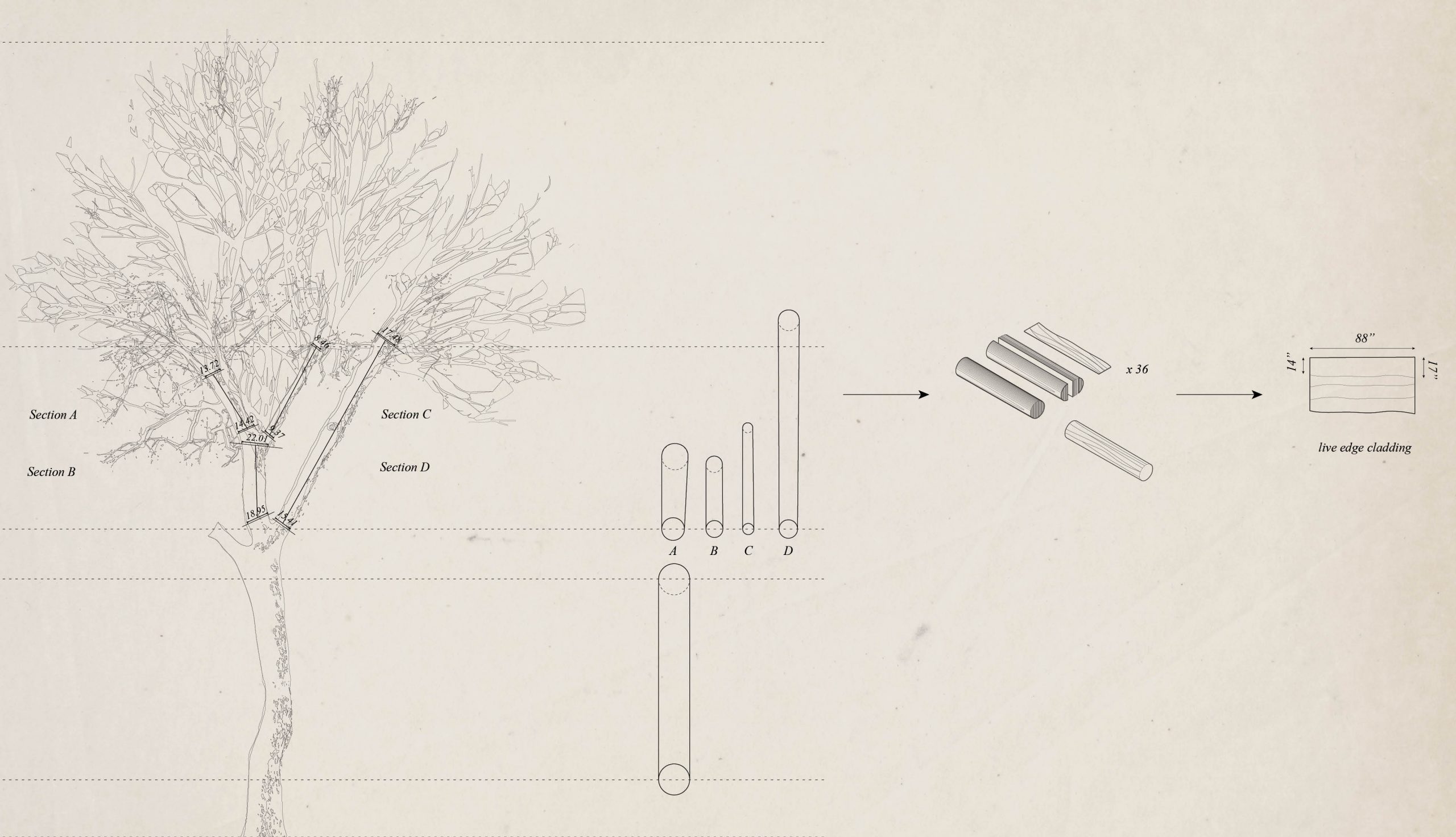

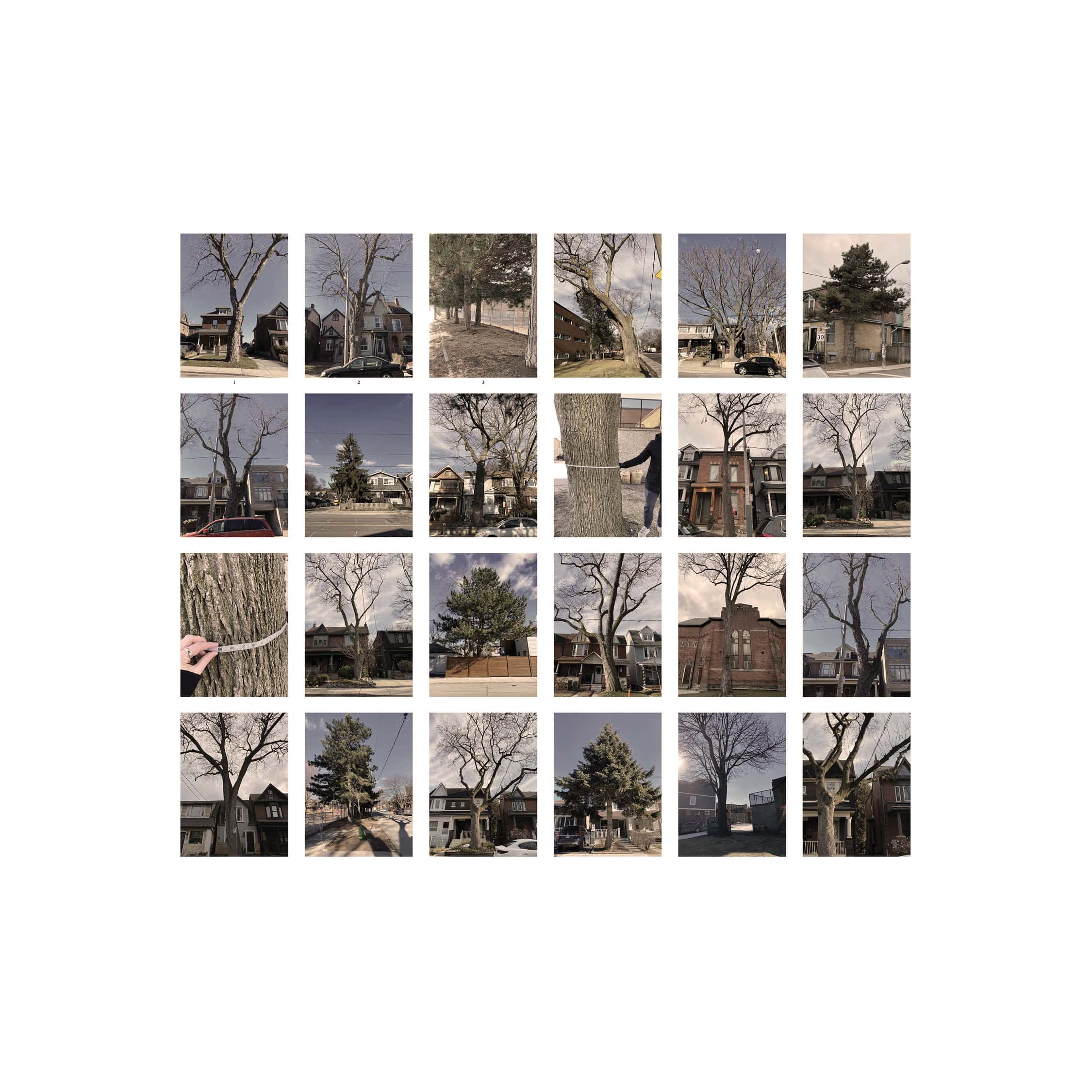

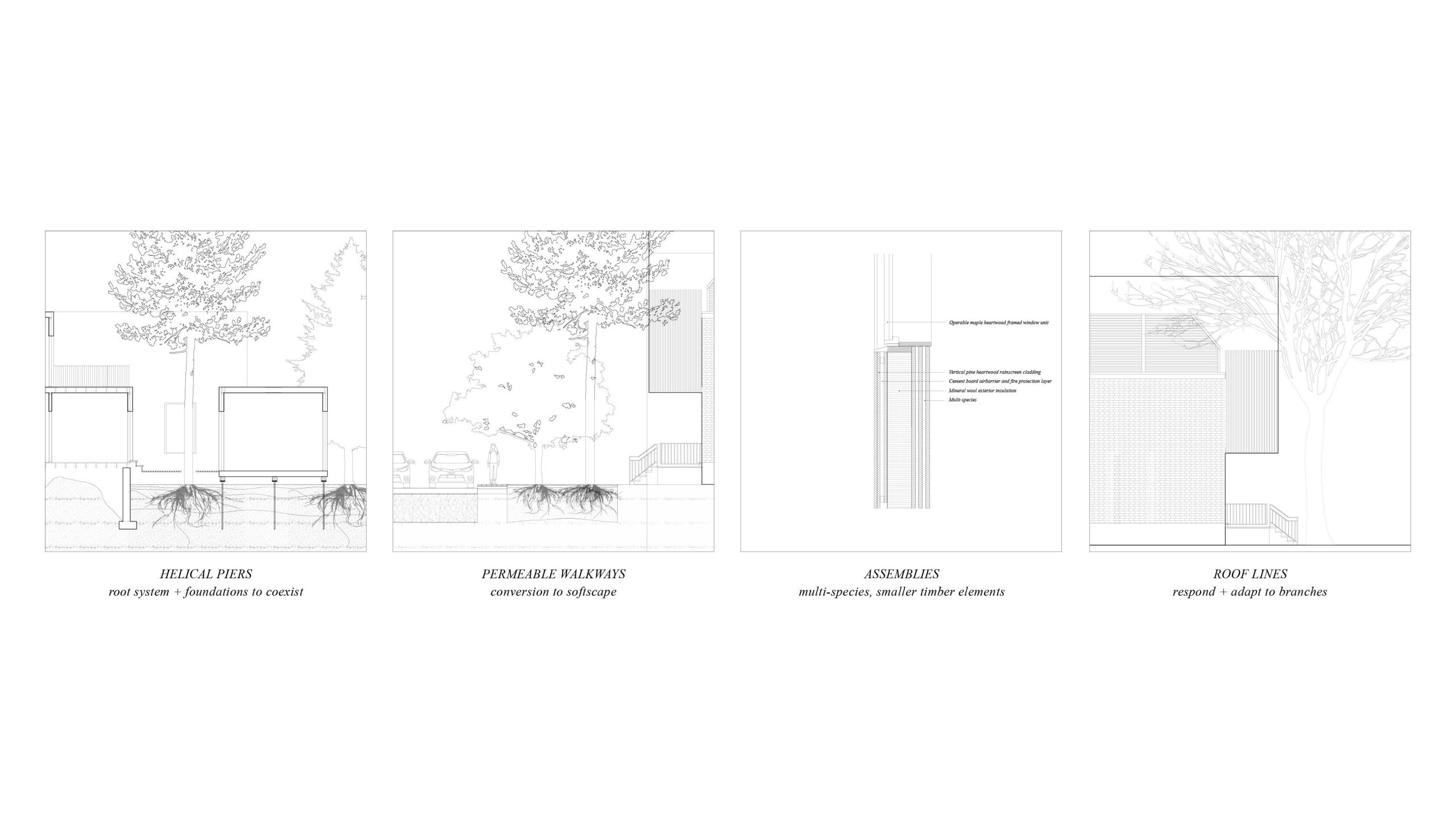

What if the city’s growth were tied to growth of the forest? How might the forest dictate the resulting architecture and urban form through the use of lesser known species, smaller timber elements, and perhaps those subject to bug infestation or damaged from climate events? Encouraging the use of our urban trees in residential construction creates a self-sufficient carbon cycle, utilizing the full potential of a variety of species.

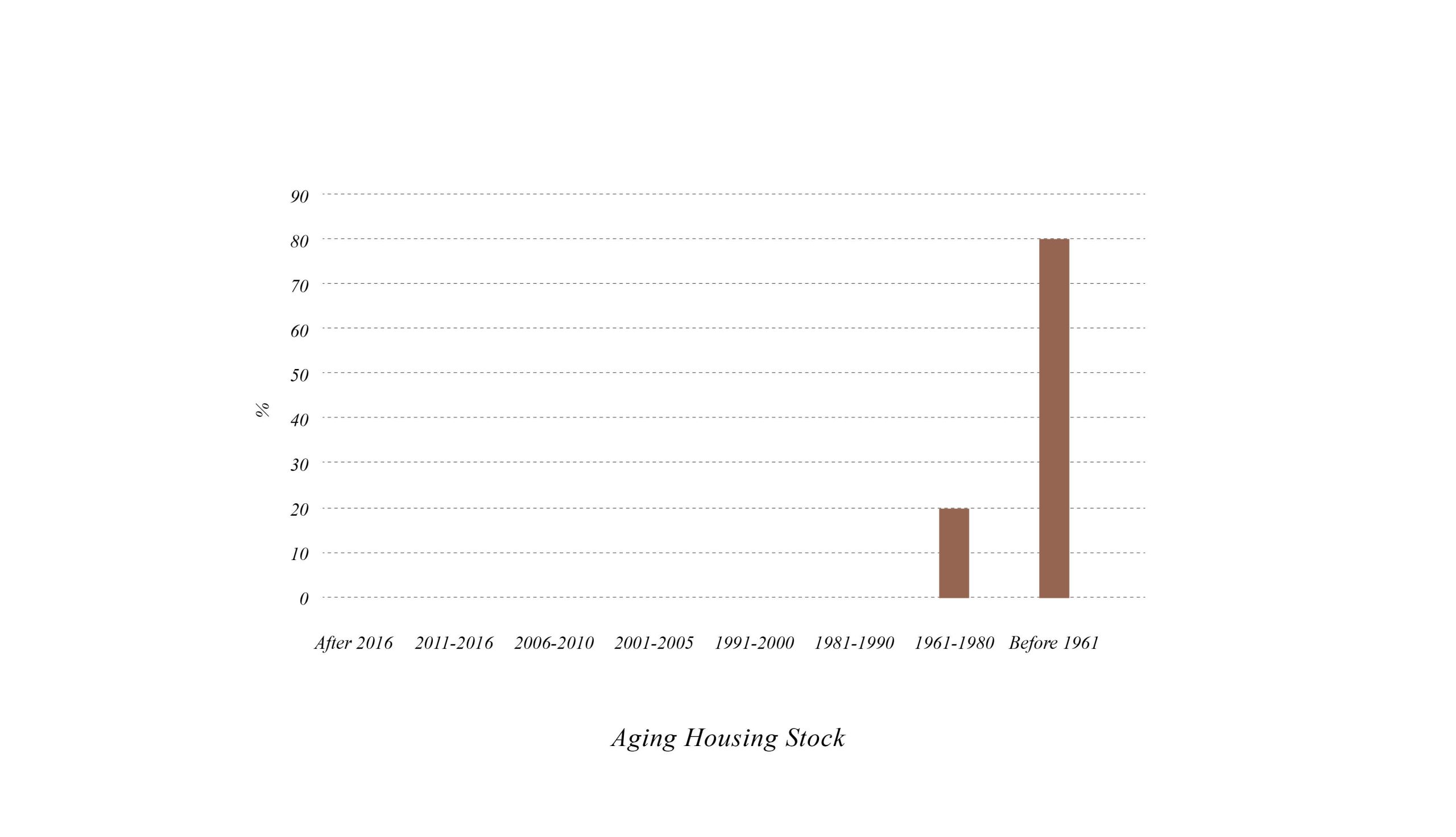

We have have an aging housing stock with century old homes built primarily before 1960 in need of renovation. This becomes problematic in that 85% of parcels with building permits are correlated with parcels showing tree cover loss.

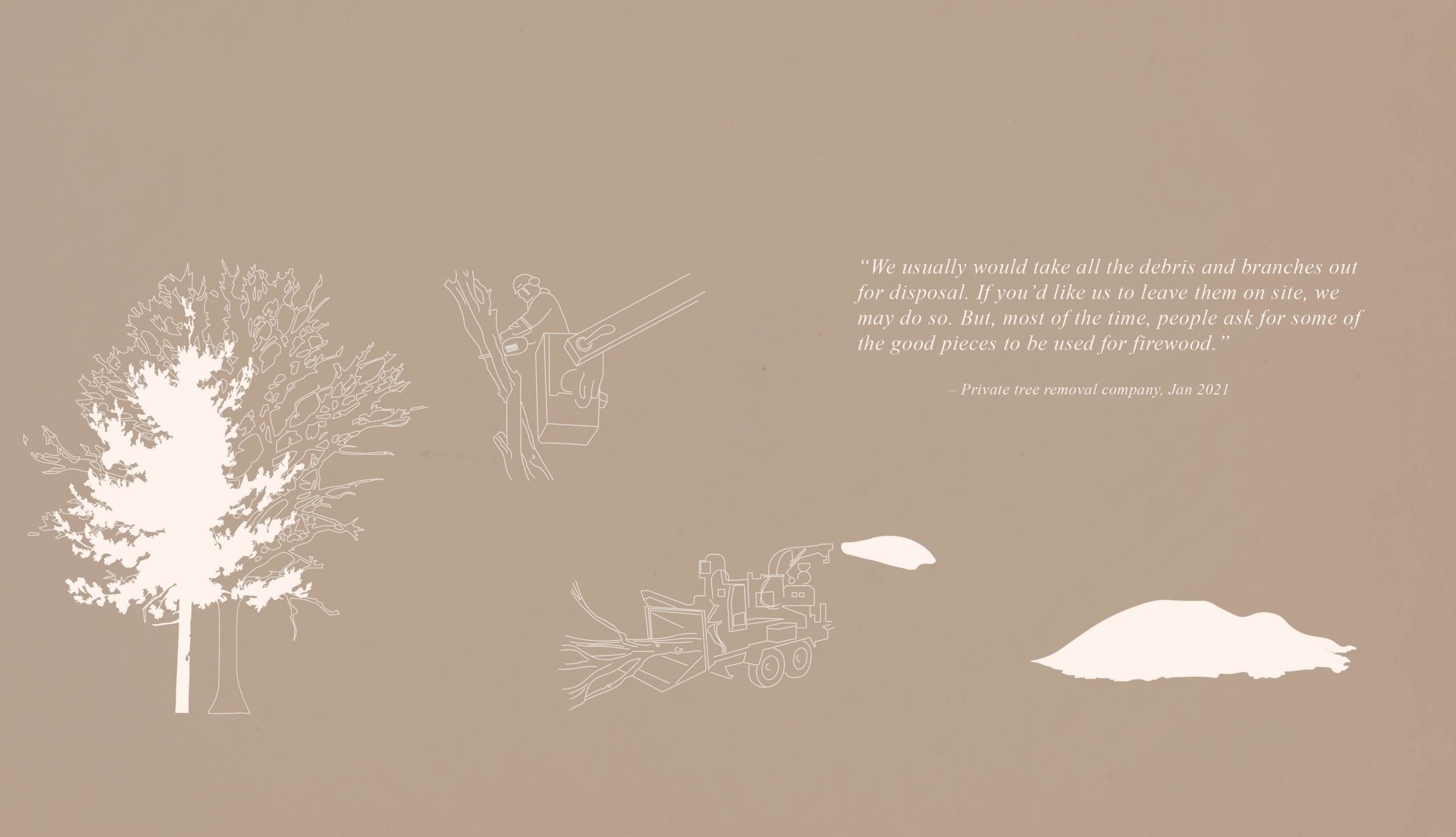

Oftentimes our urban trees are removed and chipped on site. How can we learn to see our urban trees, not as mulch, but as an opportunity to convert from one form of carbon storage to another, into our built environment?

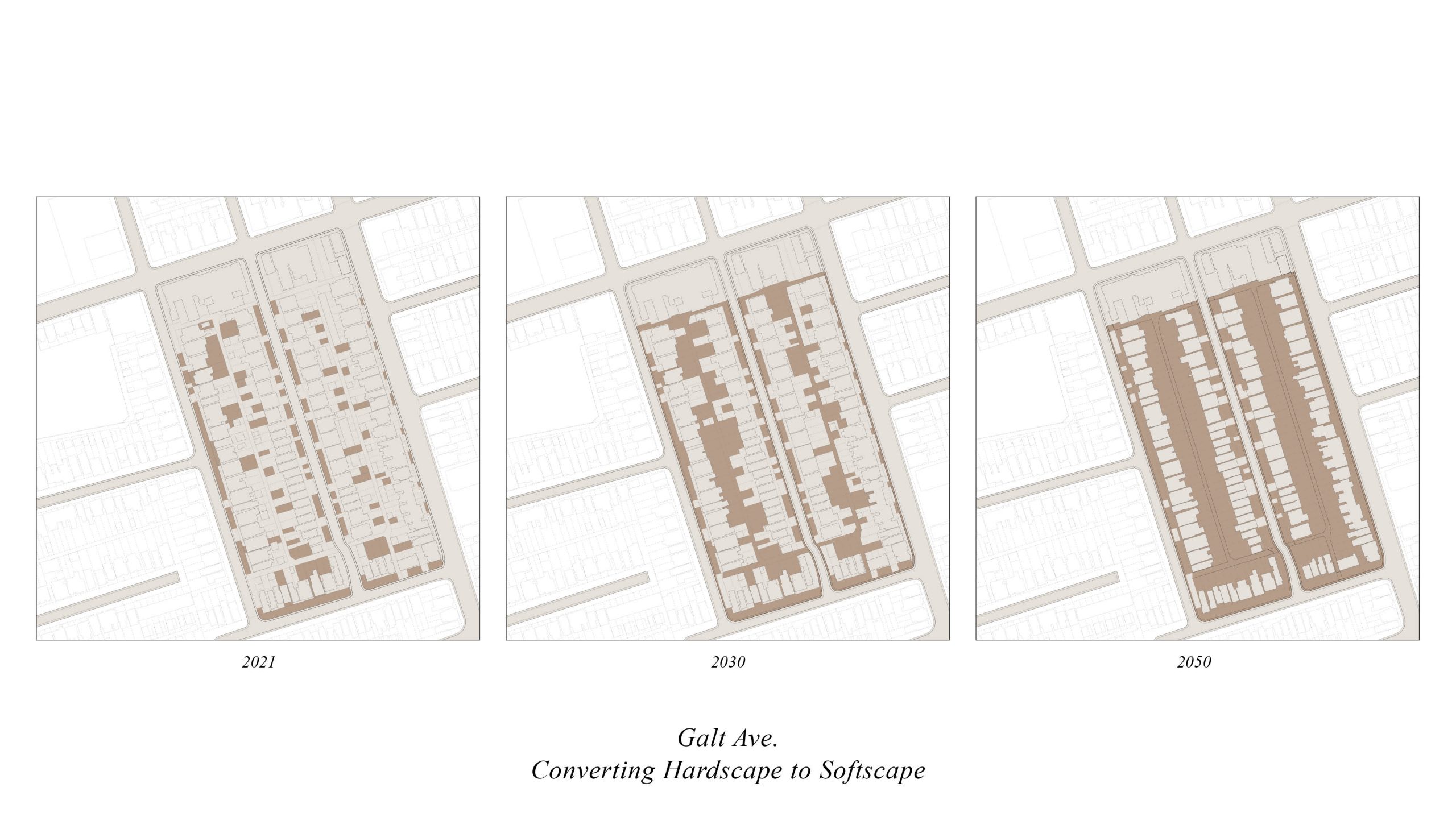

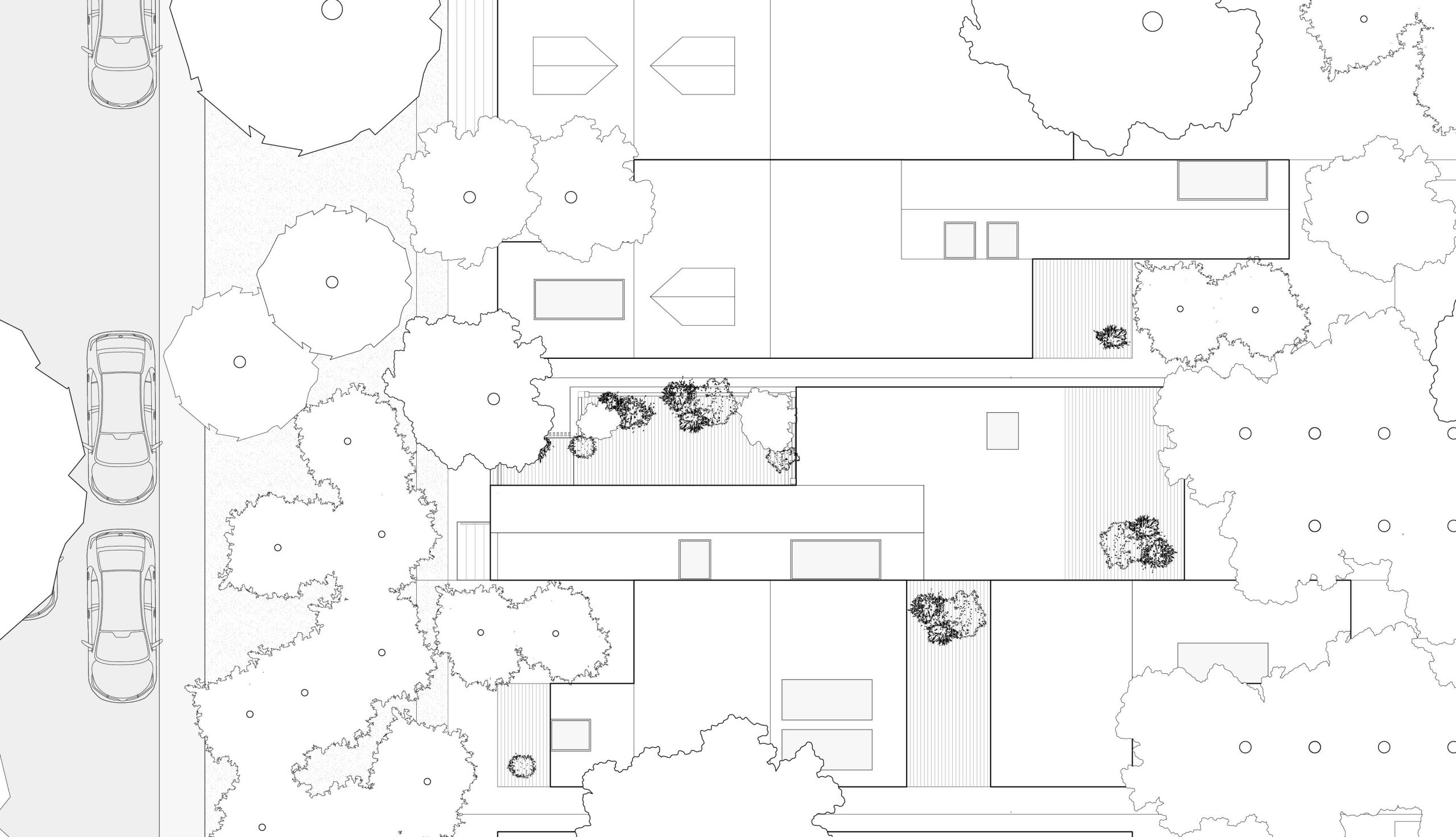

There are three strategies to reforest the study area: the public street, private yards and public laneways.

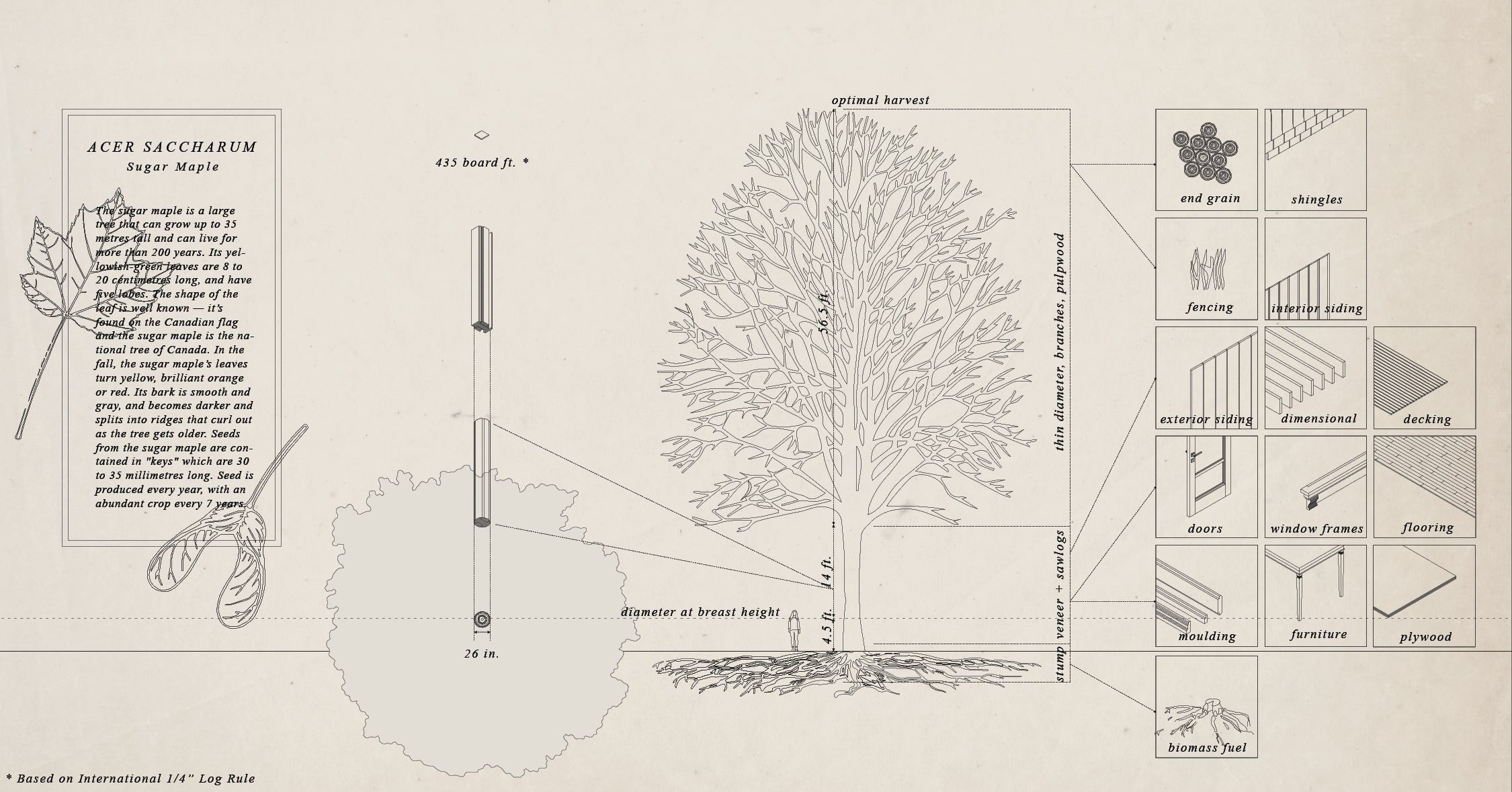

A snapshot of the diversity of species that could be utilized in the construction of various building materials. Shifting away from seeing wood as a homogeneous material results in a more diverse forest, maintaining the balance between desirable wood species and the values associated with multi-species forests.

The form of the pilot neighbourhood within Leslieville metabolizes – decisions are made by residents to remove garages/sheds, to convert laneways or parts of laneways to reforested regions, to allow for a variable setback in a façade to accommodate new tree growth, all based on new priorities around densification and reforestation. Through the introduction of a modest front addition to the existing semi-detached structure, we can increase the number of households within the study area, addressing Toronto’s missing middle.

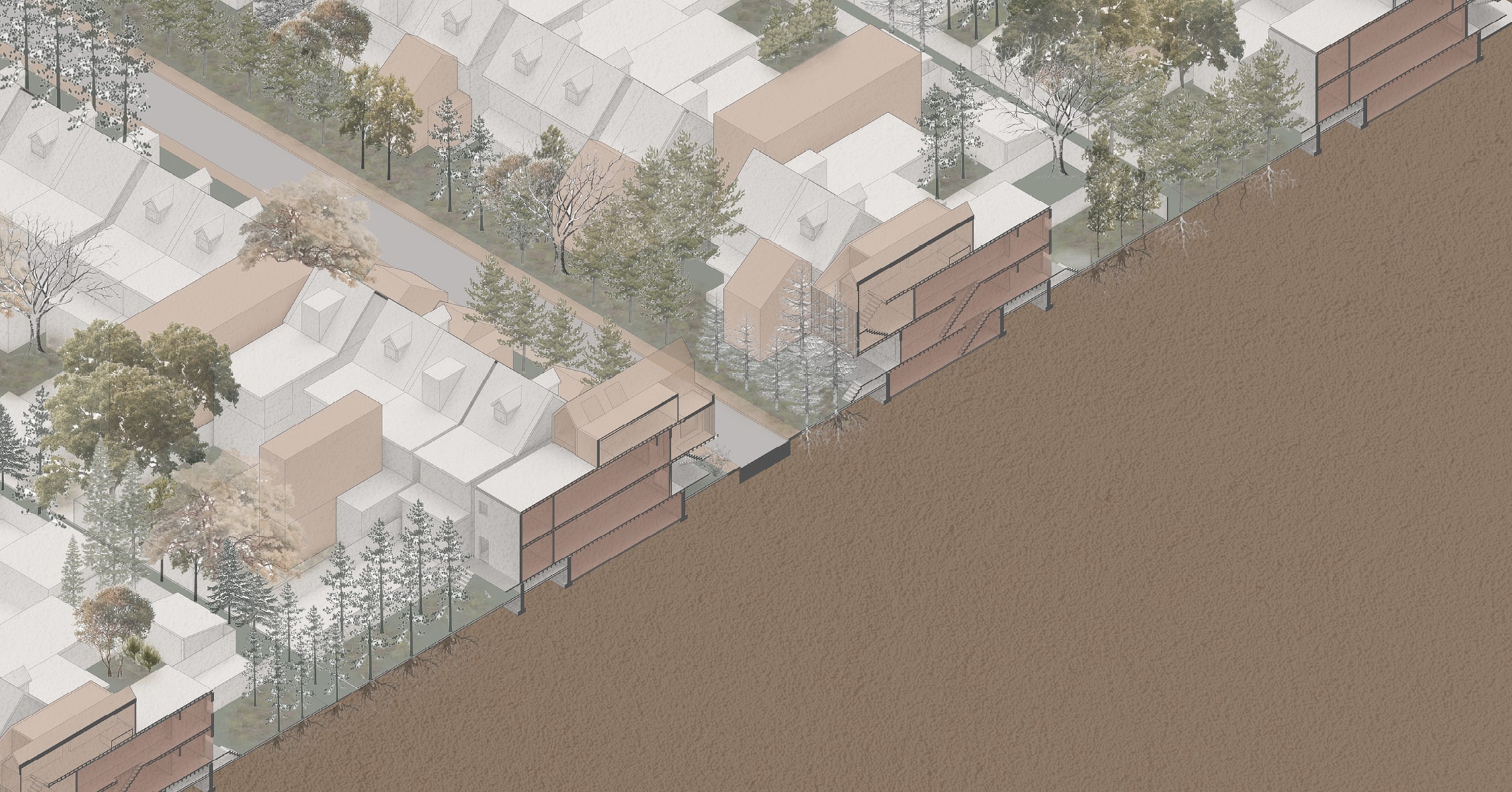

We see how the semi-detached typology evolves over time, adding density through front additions and back additions, while having a dense row of linear forest along the sidewalks and along the laneway.

This depicts a speculative future – an approach to city building and urban form away from one that prioritizes the car, to one that prioritizes community, well-being and the environment. If these rows and rows of underutilized garages (or, sheds) aren’t being used for vehicles, why must we maintain their hardscape? Imagine if laneways were reforested to create networks of pedestrian-only arteries running through the city, blurring the boundary between private backyards and public laneways, creating a new commons.

If priorities are based on a neighbourhood’s ability to sequester carbon or to harvest local timber in order to build and increase density, the way we approach city building changes. First, through zoning and by-laws. Second, through a new Neighbourhood Forestry Collective. Finally, through a greater paradigm shift in that certain neighbourhood design guidelines are be established to meet the priorities around supporting this pilot concept of a self-supporting carbon cycle.

Once we shift away from seeing wood as a homogenous material it will result in a more diverse forest, while generating a resulting gradient of wood products that reflect the Carolinian hardwood forest.

How might we re-imagine life within a city tied to slow growth?

The evolution of wood – from seedling, to forest, to timber construction – re-conceptualized as part of a single, continuous cycle.

Lessons from the past lend clues to how we might build our future, into a vision for how we might dwell and clear in the same space. In speculating on an alternative way to grow, an alternative way to manage a new urban forested landscape – one that exists in the grey area between public and private – it offers a solution for how the GTHA might rebuild itself.