The following thesis is brought to you by the Gradual Civilization Act of 1857, The Potlatch Law and Section 141, Indian Act, Reserves, Royal Proclamation – 1763, The Residential School System, the Sixties Scoop and the White Paper – 1969. A child born today can be affected by laws written in 1857. These repercussions go beyond intergenerational trauma and are perhaps now rooted in an individual’s identity.

This thesis aims to study how the architecture of child and adolescent psychiatric facilities could evolve to better cater to first nation communities. Children and adolescents learn from their environment to shape their ideals, behaviour, and values. They need to heal in an environment engaging in their historical and cultural roots through knowledge from elders in their community; A space where they could begin to reconcile with their past actions with the guidance from their nation’s principles and somatic psychotherapy, resulting in resilient adults. Unlike the current therapy system, healing in a familiar physiographic environment that embodies their historical and cultural principles will allow the child or adolescent to build a stronger identity.

“In the First Nation worldview, a child is not a tabula rasa; a child is born complete. The child is an extension of their history; they are the grand-child of their ancestors and the grand-parent of the coming generations. Within them are the past, present and the future.” -Douglas Cardinal

Vancouver Island First Nation Language and Nation Map. Vancouver Island presents a sample of the Canadian mental health climate. The Kwakwaka’wakw, the Nuu-chah-nulth and the Coast Salish house various tribes, each with different languages and dialects. Thousands of years ago, there were no boundaries or property lines; land and water was preserved for future generations. Their historical practices for everyday life, ceremony and healing were strongly embedded into the resources provided by their ecology and geography.

Bathymetry and topography model of Vancouver Island representing the physiographic nature of the island. There is an intricate dialogue between water and land. Today, First Nation communities are confined to reserve land. Modelling the area of reserves on the island and their transportation connections brought to light a linear representation of their relationship. Rarely were first nation communities close to each other; many first nation communities were miles away from a current people city. In many cases, there was a lack of access to necessary amenities and historical resources for sustenance and activity, precursors to the current Canadian mental health climate.

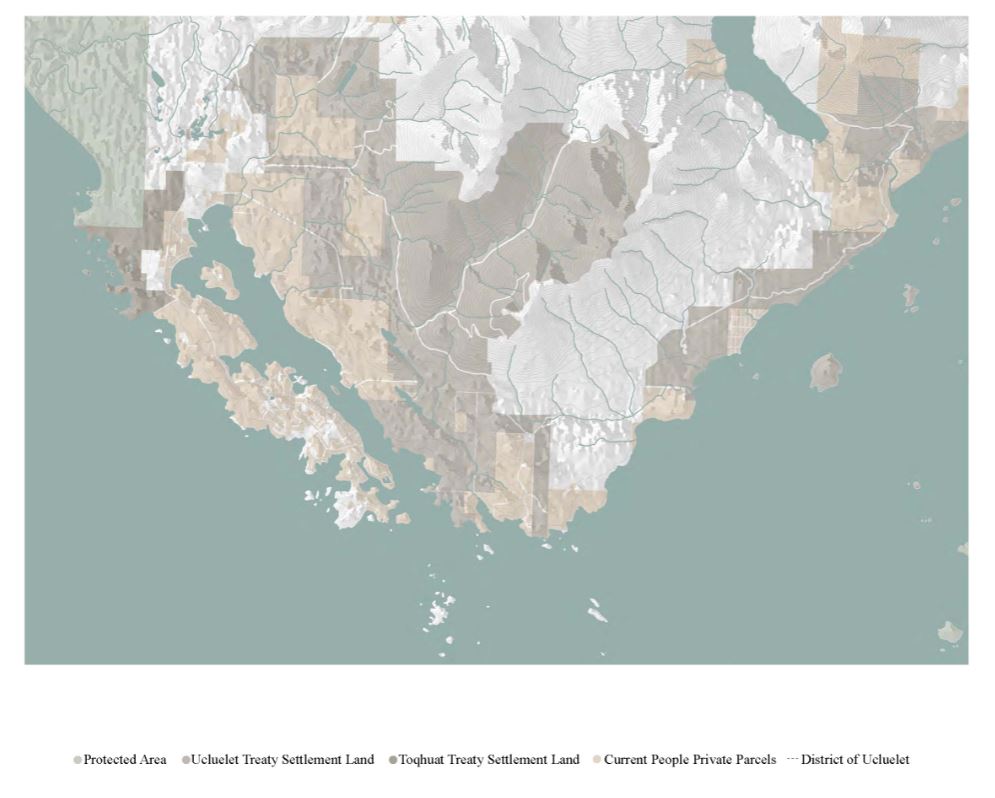

Map of Ucluelet Land Ownership. One of the rare communities that were close to a current people city was Ucluelet, adjacent to the Ucluelet First Nation and the Toquaht First Nation. The site the Current People Community sits on was once a part of the Ucluelet First Nation. Before European settlers arrived in Canada, Ucluelet was home to the two Nuu-chah-nulth populations for 4300 years. Social tensions in Ucluelet increased in the late 1800s upon settling fur sealers in 1870 and establishing a trading post in Ucluelet harbour. Evolving from an industry trading post to a military base in World War two to a hot spot for lumber cultivation and manufacturing, Ucluelet is a sample of the political tensions ever-present in a Canadian city.

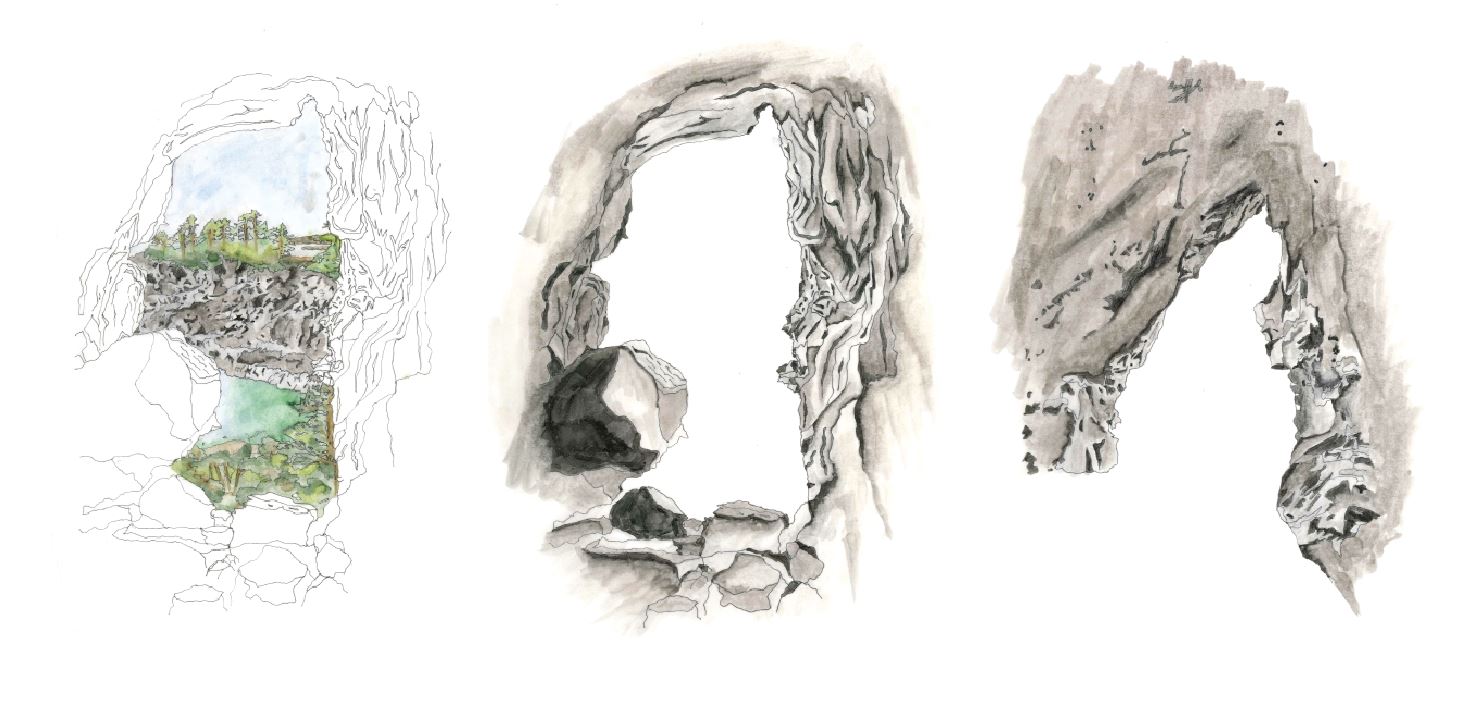

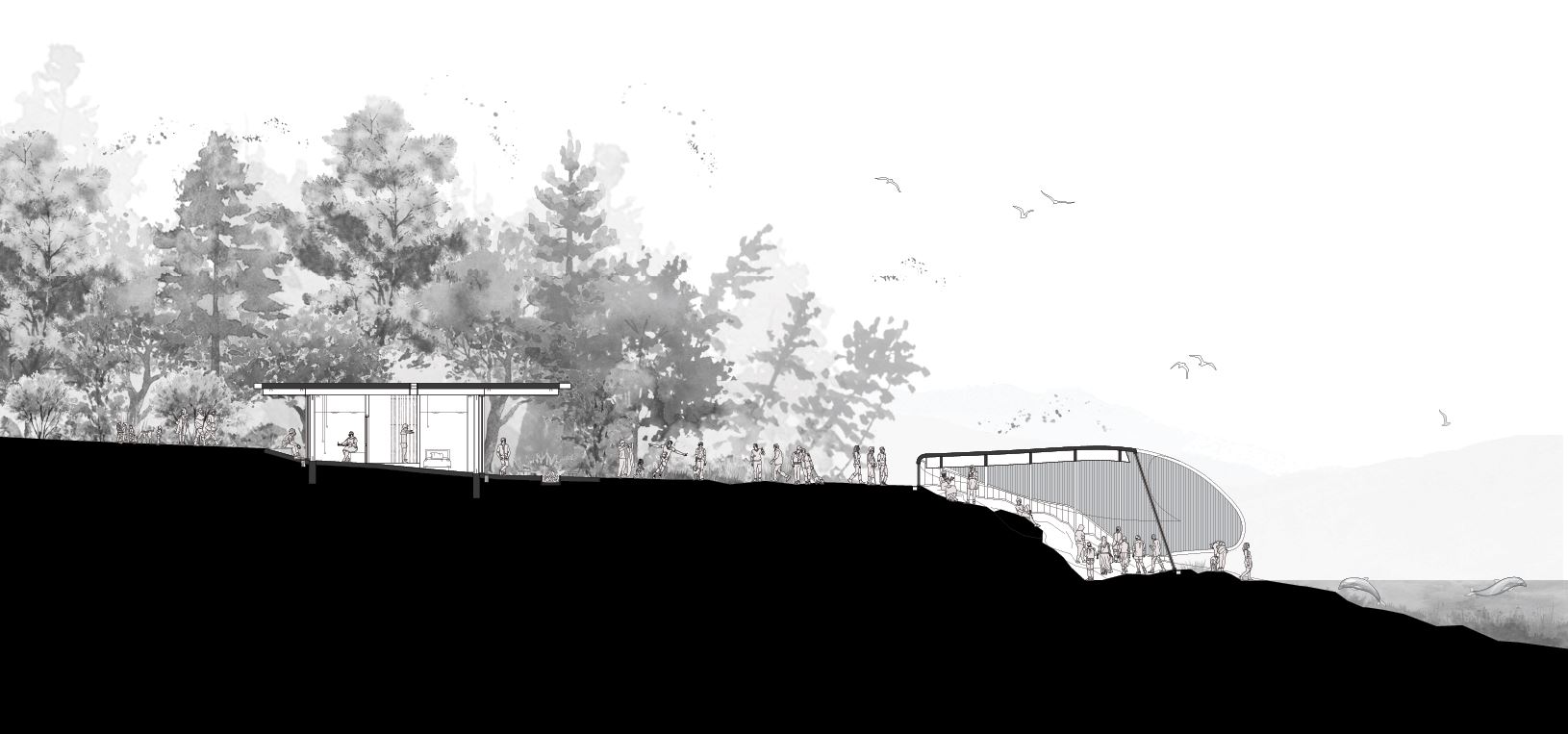

Equidistant to both first nation communities and the current people population lies a beautiful cut into the rocks. One adjacent beach belongs to Ucluelet, and another belongs to the Toquaht First Nation. This site acts as an incubator for the architectural exploration of the psychiatric facility. The experience of the Ucluelet environment is studied by analyzing how the physiography of the site naturally creates shelter and space, while framing views to it’s adjacencies and the ocean beyond.

In this proposal, the healing environment and the architecture are both products of the site’s climate and ecology. Healing is embodied in the stones, the spruce, the cedar, and the water. They are elements of Nuu-chah-nulth stories, teachings, songs, and chants. The architecture was driven by cultural and historical practices that are important to the Toqhuat and Ucluelet First Nation.

Water is purifying. The architecture extends existing planes already present in the environment towards the water. The extensions act as an invitation for the inhabitants to look to the water and allow their senses to experience the cusp of the ocean beyond. The architecture acts as a suggestion, or a reminder to reconnect with the ecology and their historical practices, growing their knowledge of their identity and laying the groundwork to grow their sense of self.

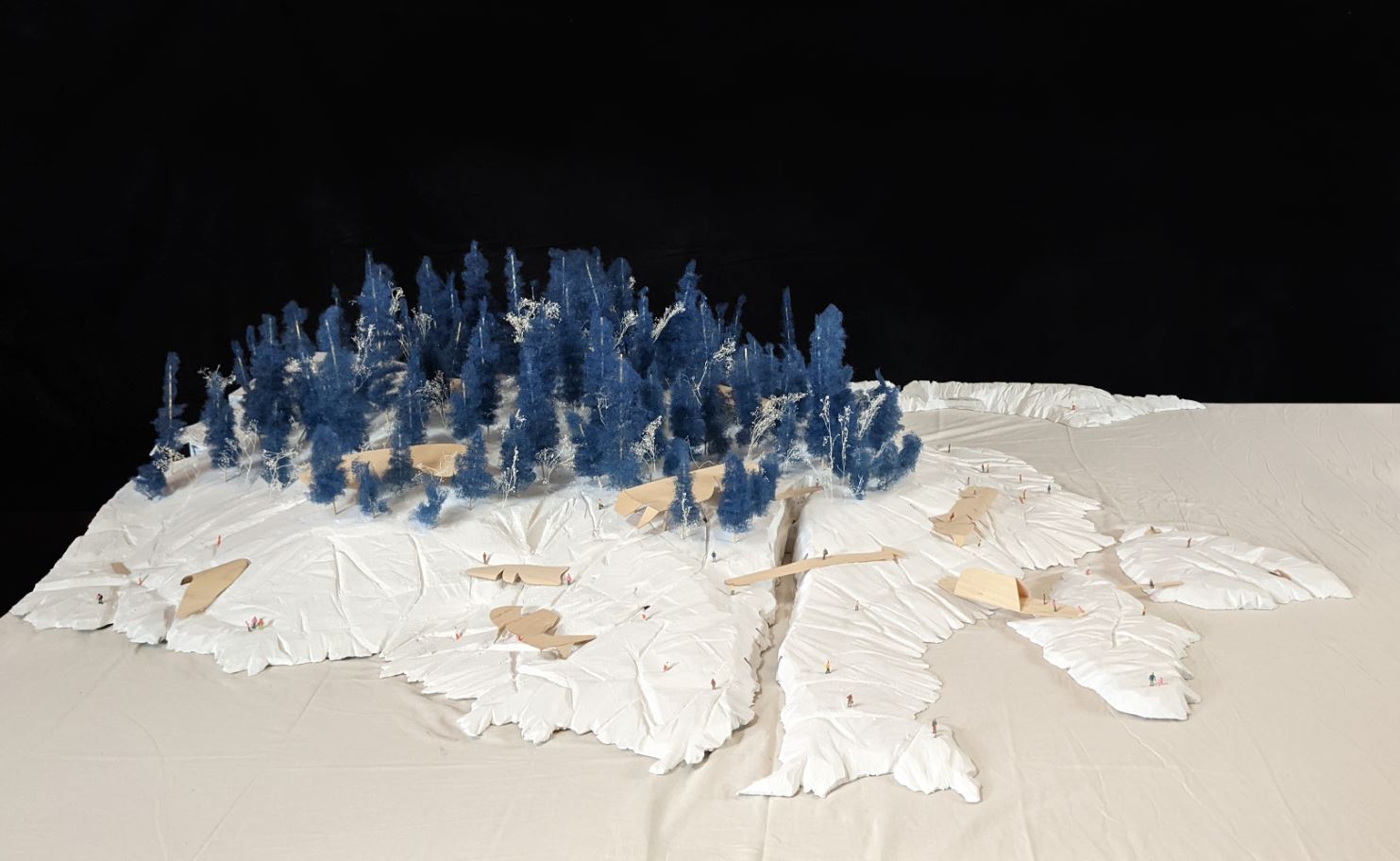

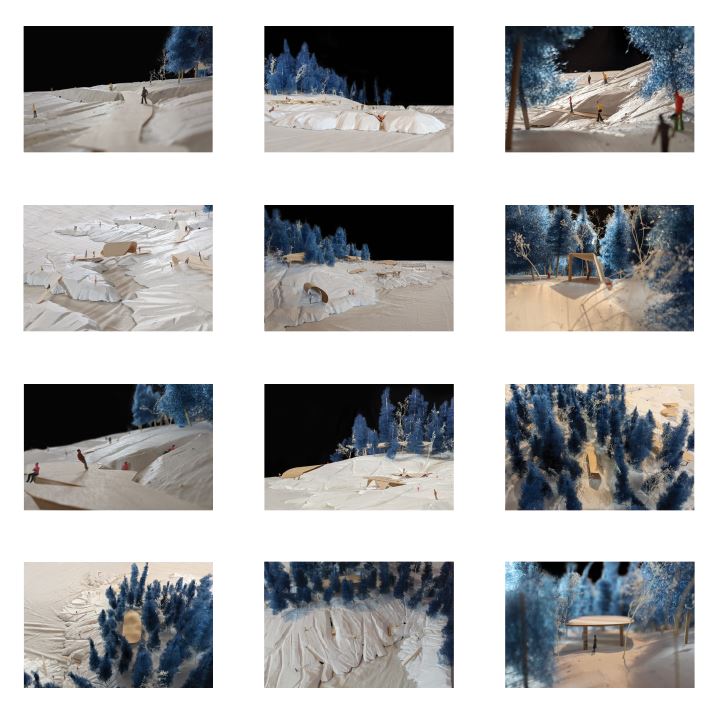

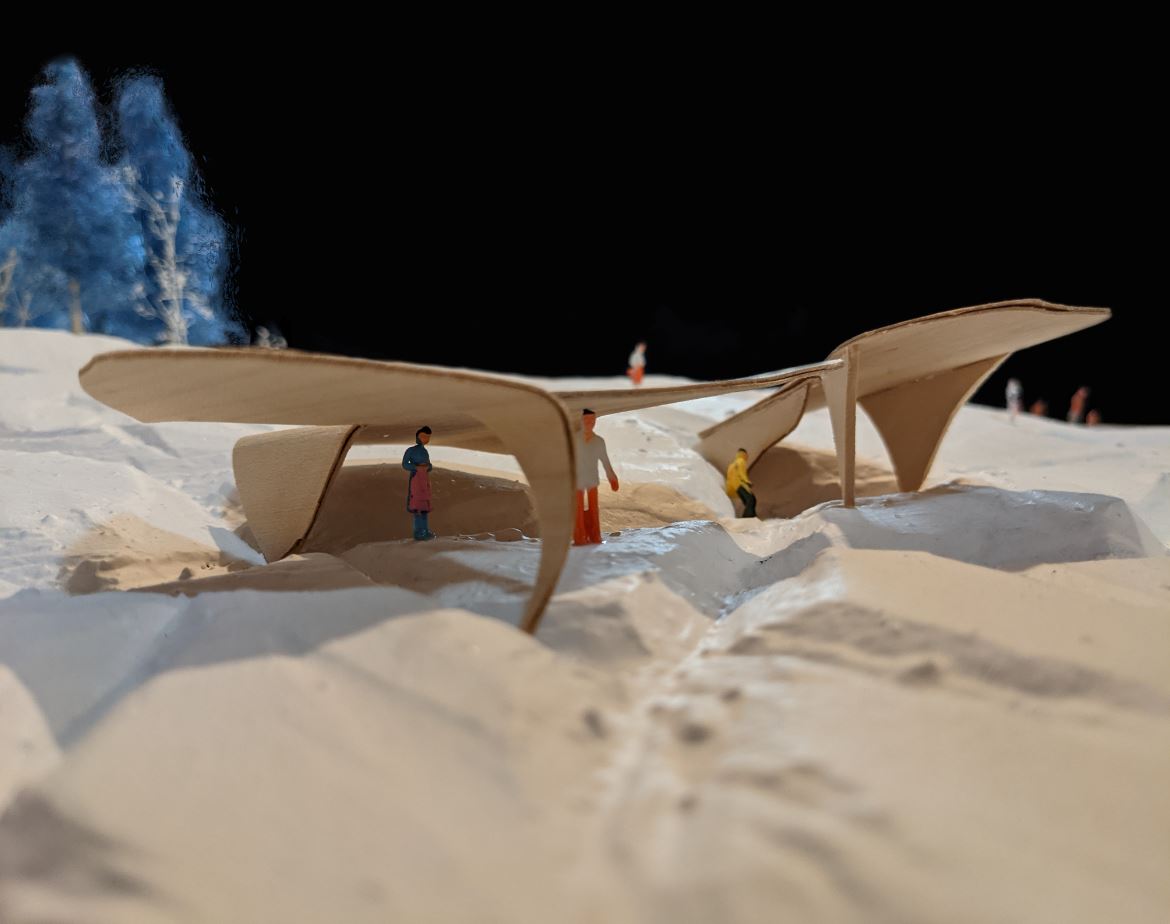

The child and adolescent psychiatric facility requirements are grouped into planned (1) the arrival or introduction area, (2) living spaces and, (3) therapy spaces. The living spaces are dedicated to the adolescents and children being treated by the facility. Patients and visitors are received in the arrival area. The architecture aims to showcase the ecology. Each area responds to its immediacies through form and materiality. Indents in the topography are the precursors to the architecture.

Many Nuu-chah-nulth stories and teachings relate to flora and fauna in their region. Patients connect to their roots by traversing and embedding themselves in their history through physiography. Spruce and cedar are essential elements for the Nuu-chah-nulth. Cedar is protection. The structural and malleable limits of the timber define the limits of the architecture.

The architecture aims to showcase the ecology. The intentional, planned acts of the built form embrace elements of therapy that were perhaps always there. In some ways, the architecture need not exist, just its intents and implications. Perhaps the only everlasting indicator of architectural existence is the paths created by human movement when traversing from one built form to the other.