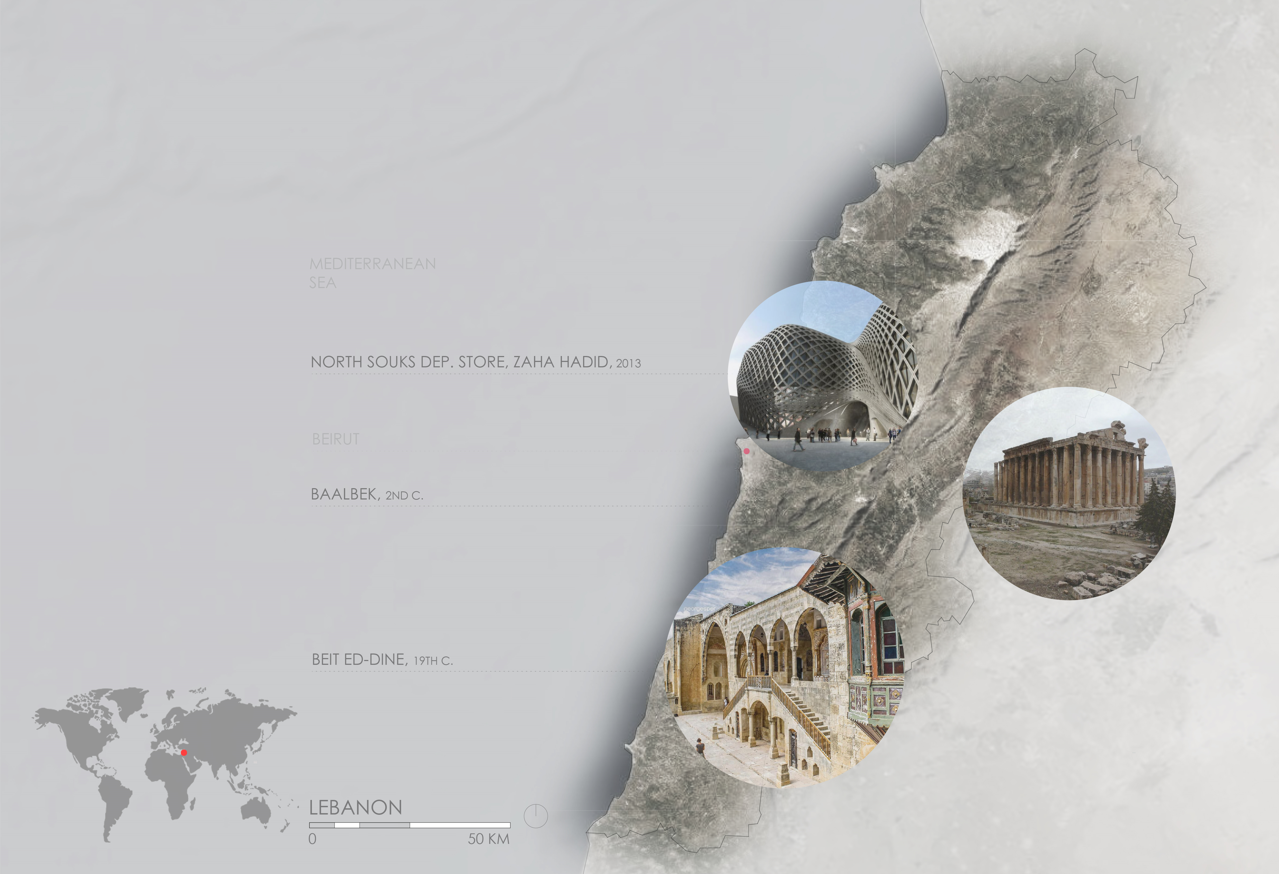

Officially known as the Lebanese Republic, Lebanon is a 10,452 km2 country located in Western Asia. Its neighboring countries are Syria, Israel and Cyprus as Lebanon is located centered on the Eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea. This country is recognized by its rich history and multicultural identity as it consists of diverse religions and ethnicities. This small country has survived through and adapted architectural characteristics from the Roman Empire in 64 BC, the era of Ottoman rule that lasted through World War I, the French Mandate colonial period before Lebanon’s independence in 1943, and the modernist period before 1971. Thus, ancient temple ruins, castles and a variety of religious monuments now lay scattered across the country. Post WWII, Lebanon became a tourist destination; Beirut, Lebanon’s capital, was nicknamed the Paris of the Middle East due to its French influences and vibrant multicultural lifestyle.

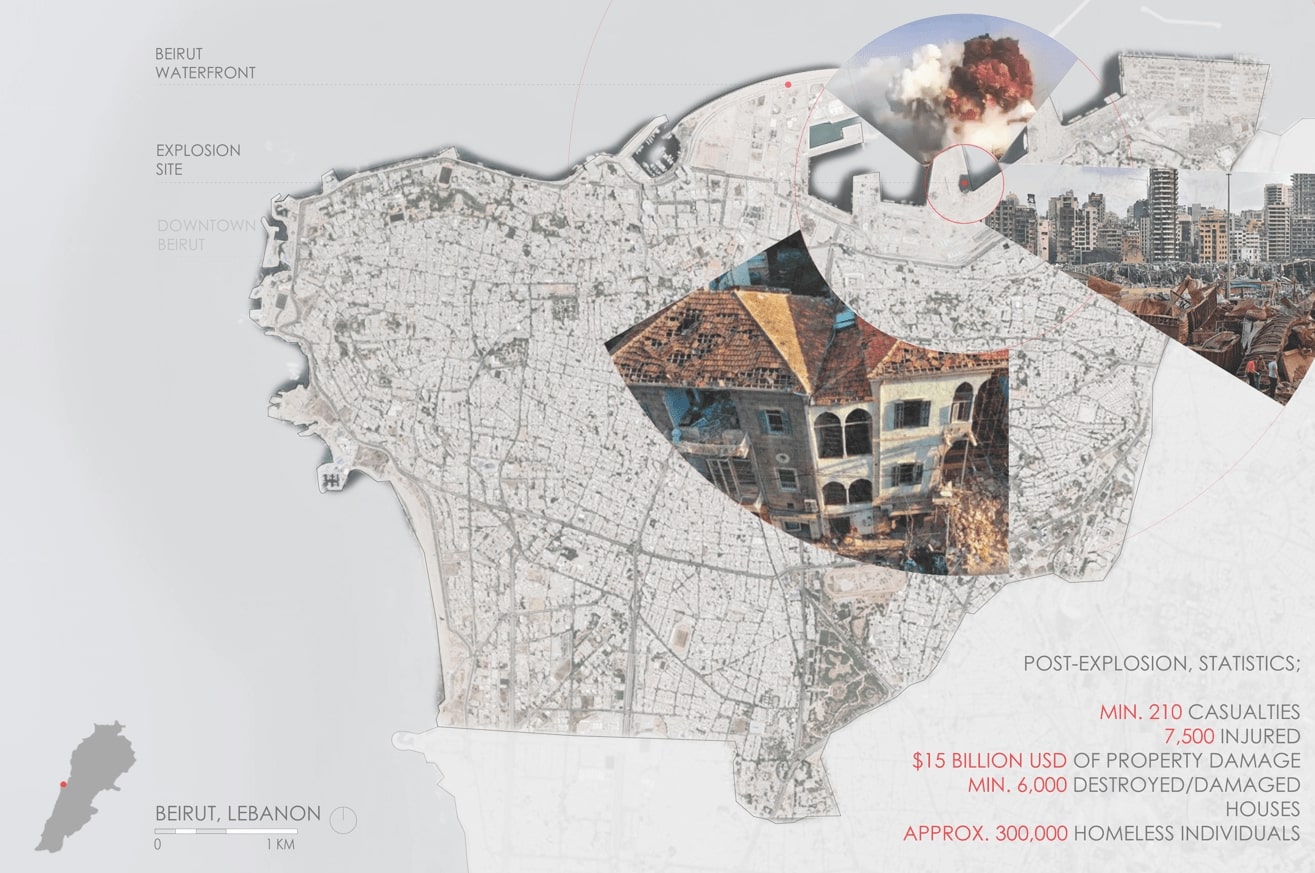

On August 4th, 2020, the humanitarian and economic crisis in Lebanon was exacerbated in the aftermath of the devastating chemical explosion located at the Beirut Port. As the ignorant and corrupt government have left 2,750 tones of ammonium nitrate illegally and unattended for 6 years in the port, as many as 300,000 citizens, not taking into account the many killed, have been displaced from their homes while over 6,000 buildings were either damaged or destroyed. The Lebanese citizens continue to struggle to survive as they continuously attempt to rebuild their country during a pandemic and a state of emergency.

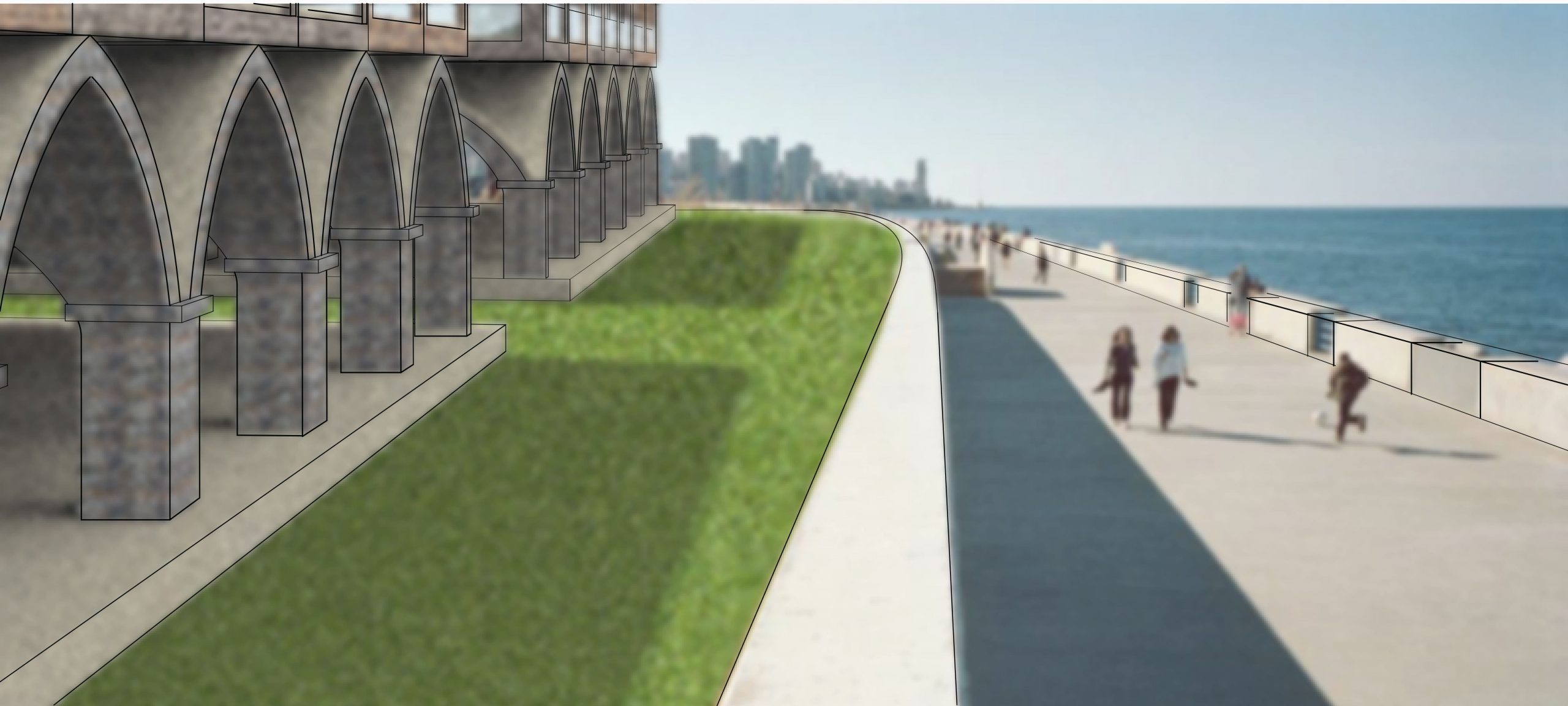

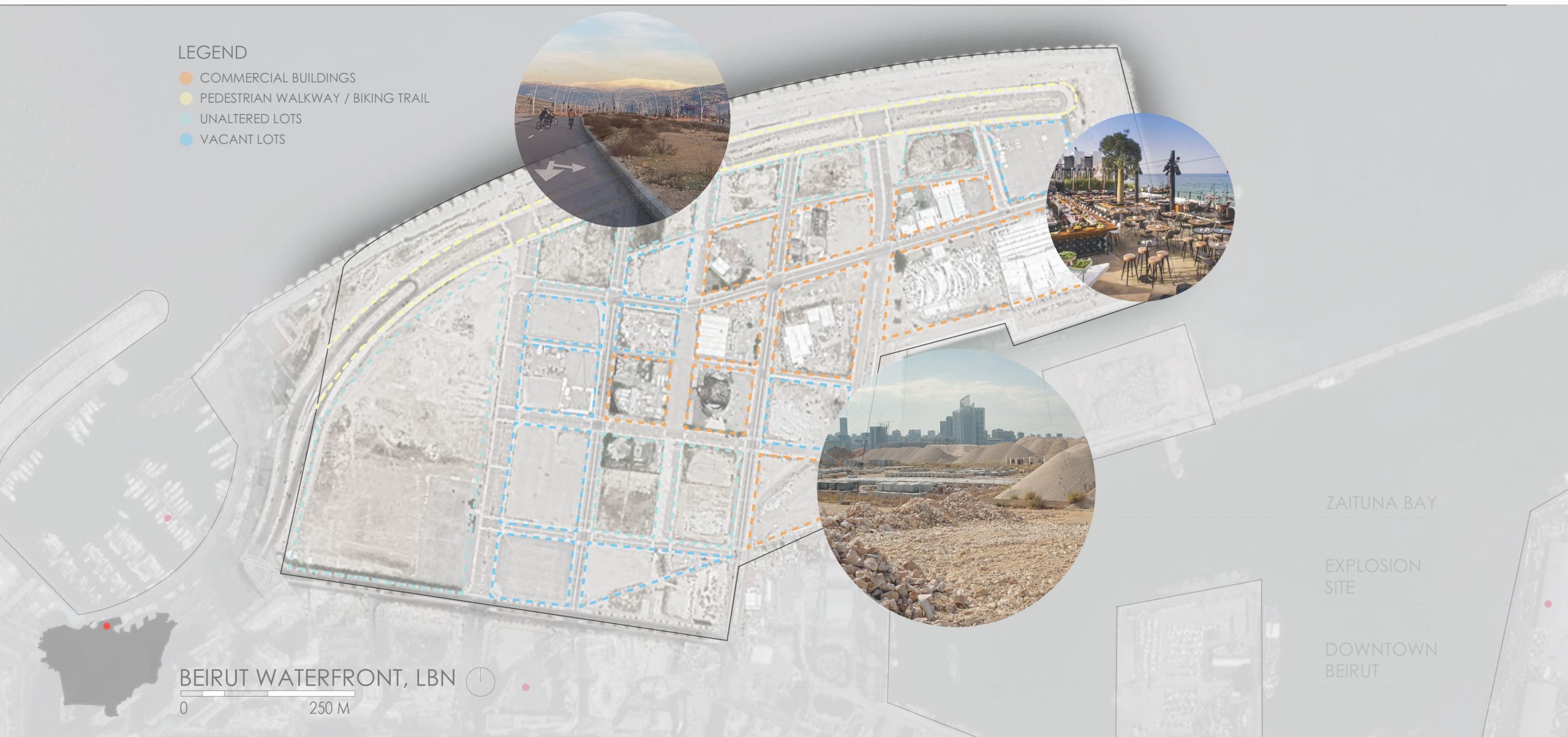

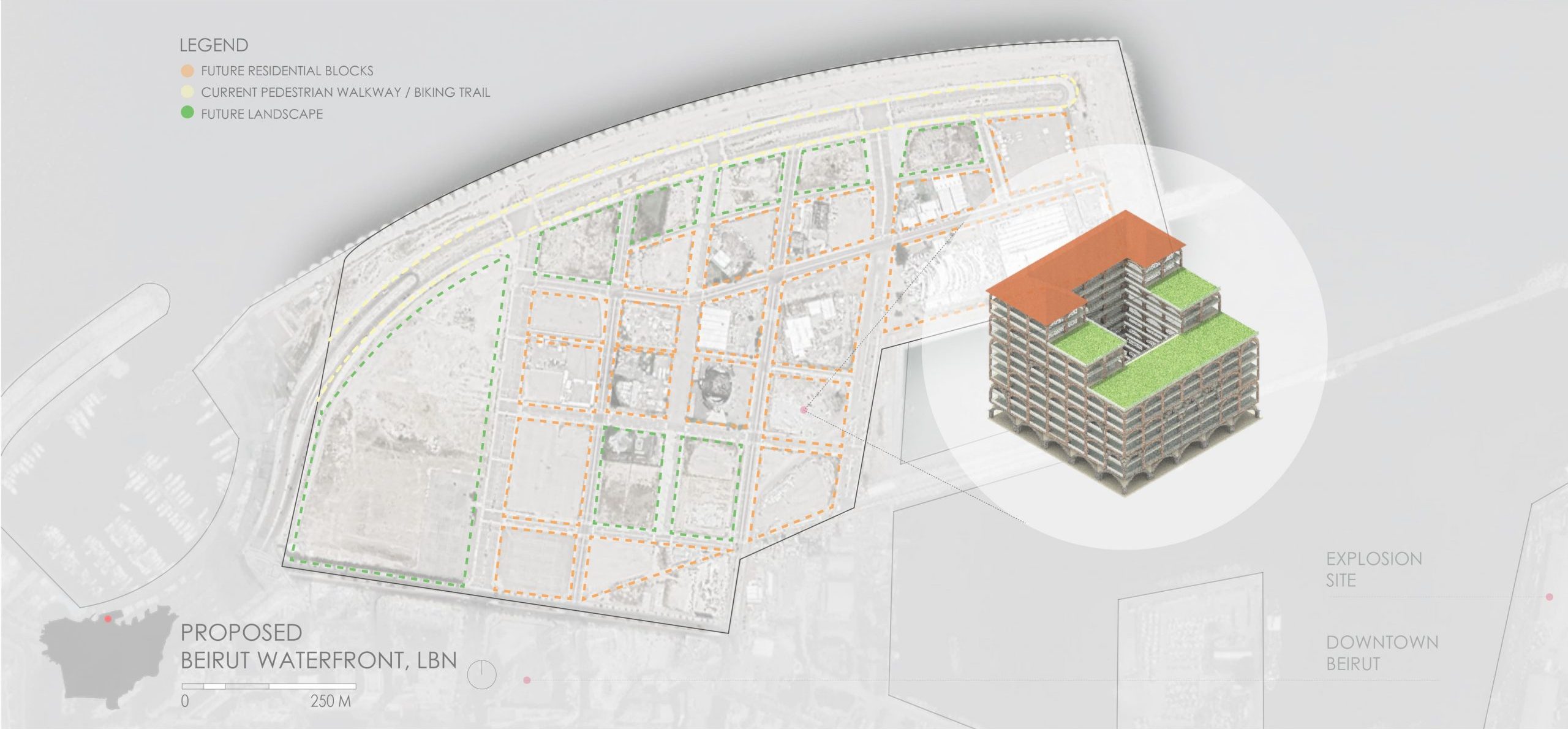

Throughout this research, it has become evident that Lebanon is now in need of a large-scale housing plan for the citizens of Beirut. Following decades of war where thousands of citizens have been misplaced, the government has never implemented emergency housing as needed and requested. Hence, this research proposes a masterplan in the vacant, 2,045,143 ft2 area in Beirut’s waterfront located one kilometer away from the explosion site. Eighteen master blocks will offer residential units to those who have been directly affected and displaced by the recent events. As Lebanon is a community driven country, it is important to incorporate the traditional design techniques and materials in Lebanese architecture as they efficiently resist the rough Mediterranean climate and define the country’s preeminent features rather than the current corruption overwhelming it.

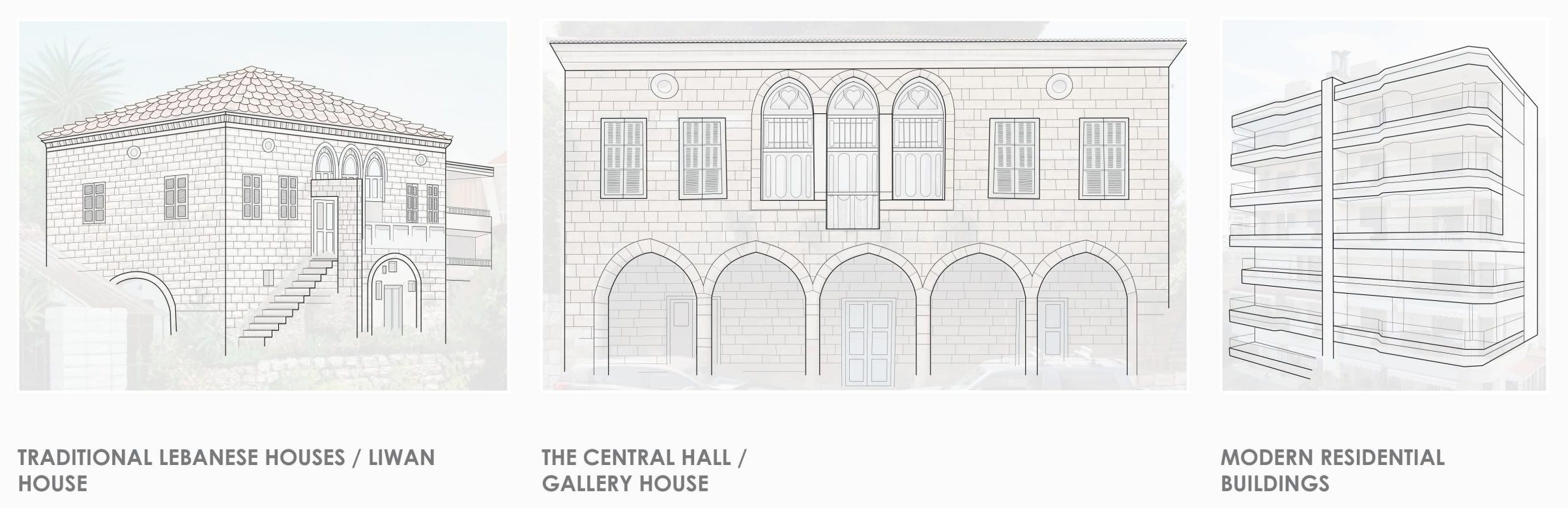

This research started with reviewing Beirut’s vast typology. The more traditional houses are highly regarded as they represent Lebanon’s culture and history; within themselves, there is history as the traditional Lebanese house evolved with time. Nowadays, modern houses are very common despite being uninteresting to the citizens.

The first form was the Central Hall / Gallery House; it dates back more than 3000 years and was well established in the 19th c.; they are extensions to the rectangular traditional house with the cross vault dome, wooden or stone pillars and a tile surface. The most common type was the Traditional Lebanese House, also known as the Liwan House, which dates back to more than 2000 years in its simplest form. Among the many variations of the traditional Lebanese house, the most important tradition was the decorative details. They define a building as traditional Lebanese architecture through their originality and heritage passed on through centuries.

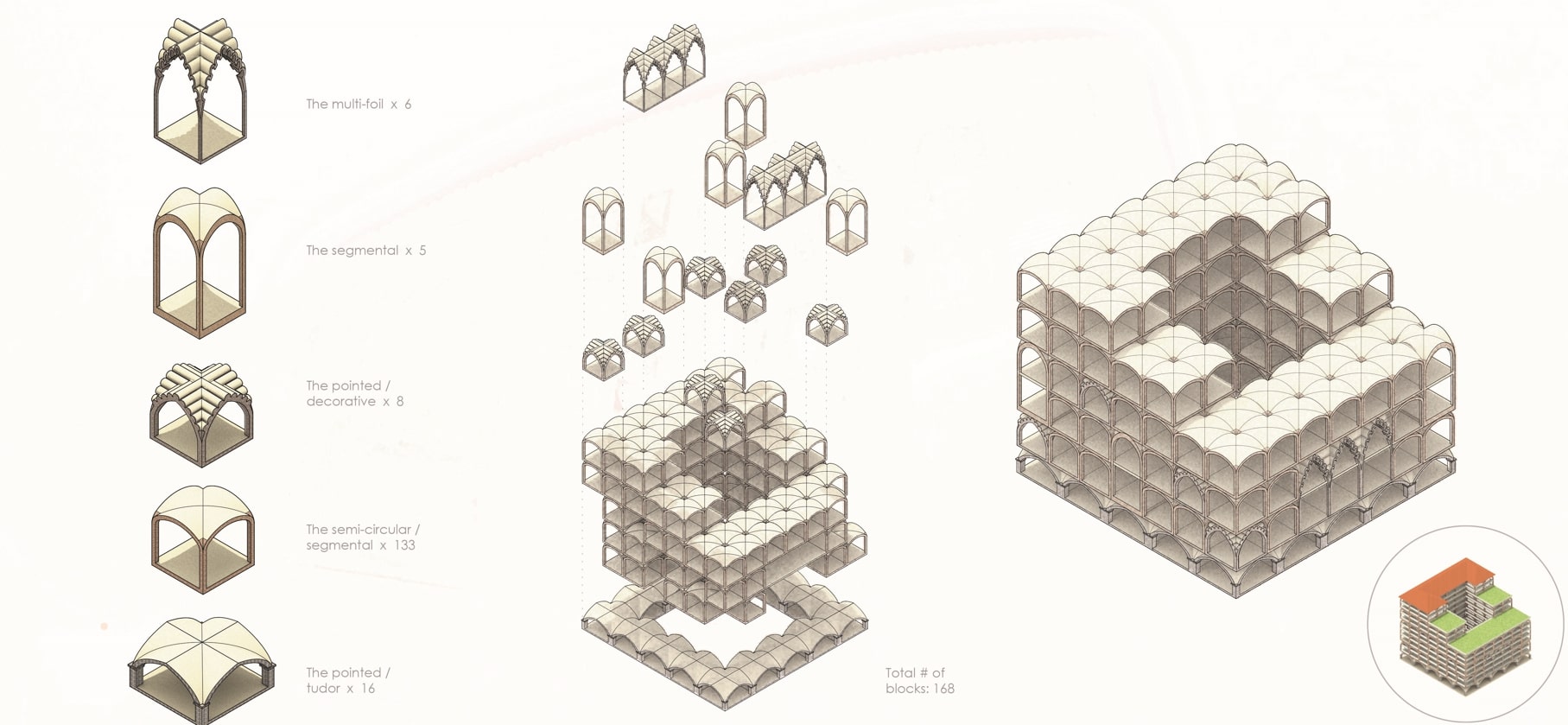

As a response, my proposal incorporates the usage of these traditional methods. By using five types of the traditional arches, the structure is fabricated and shaped by a variation of cross vault domes. This prototypical version of the proposal is formed with a total of 168 domes allowing a structured and systematic housing block. Moreover, as the Lebanese citizens are a community-oriented society, circulation and connections are essential to incorporate in this housing proposal through elements such as the central courtyard, the gallery and the balconies.

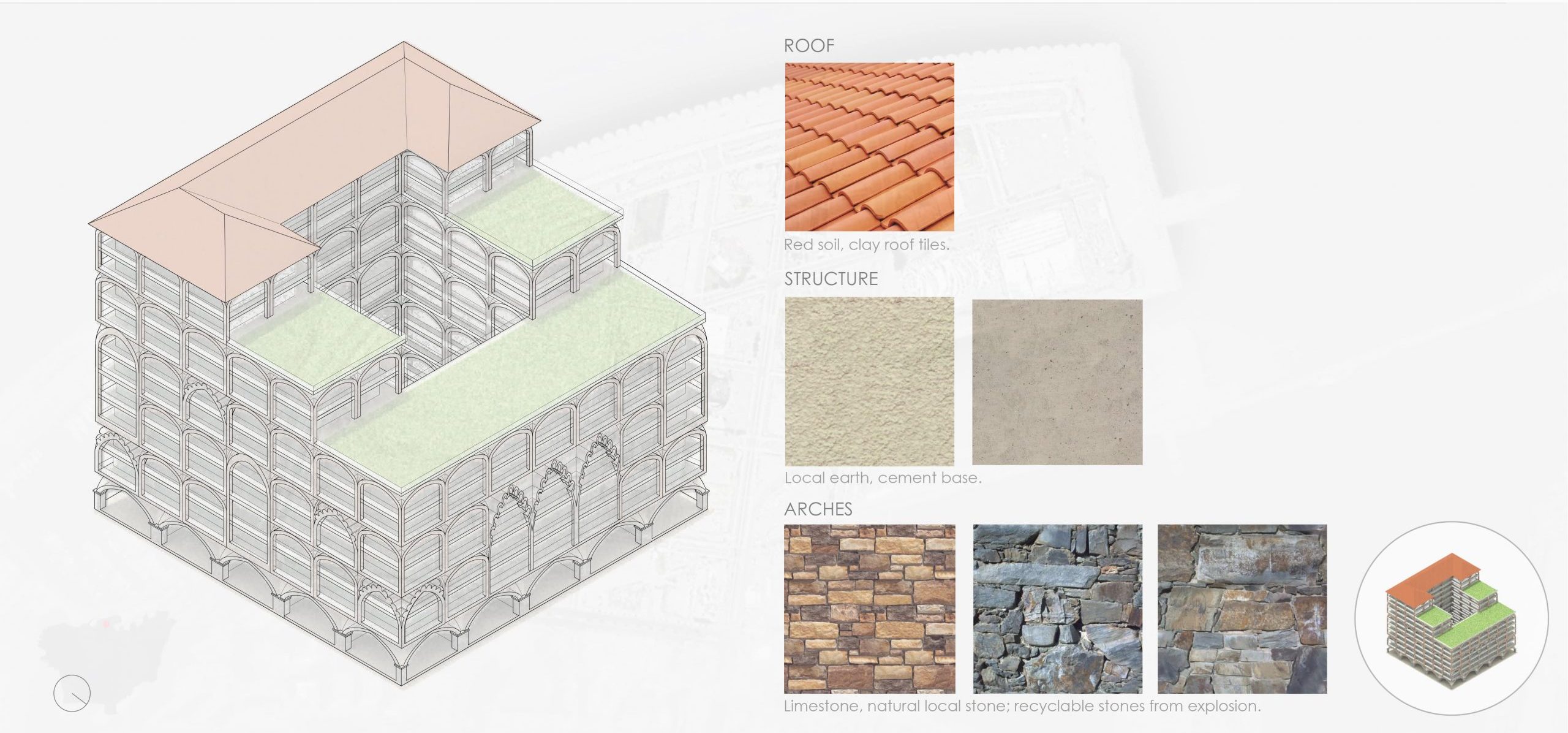

With respect to materials, it is important to consider the traditional raw materials as they are emblematic to the Lebanese identity as well as suitable or capable of resisting the rough Mediterranean climate. The roof will be made of the local red clay tiles while the structure will be constructed with local earth. In terms of the stone, they will not be limited to limestone or sandstone, as the available stones include the salvageable ones from the explosion itself. By doing so, the materials will offer a means of connectivity and memory to the Lebanese community.

Ultimately, this research proposes a prototypical approach in addressing the critical housing situation while still incorporating Lebanon’s vernacular and functional architecture. Prioritizing the needs of the Lebanese community, this proposal suggests reclaiming the large vacant 2,045,143ft2 land at the Beirut waterfront from the Lebanese government and use it for a major housing project. This proposal creates a community through the implementation of traditional Lebanese architecture; this involves community oriented spaces, the engagement with local materials and craftsmanship, and a new housing district developed together. This is a way to give back to the citizens who have been constantly and unnecessarily suffering from the conflict, corruption and negligence by the Lebanese government.