Left to our own devices, human beings are inclined to form groups

to include is also to exclude

to be part of something is to create an other

our socially structured processes, left unattended, will perpetuate segregation

(Krysan, 2018)

This thesis research examines architectural typologies and planning policies to set a foundation for building racially integrative communities.

While studies on historical examples of segregative architecture are plentiful, research on how to create racial integration through architecture is often neglected, and the topic of race has become increasingly prominent in our society. Since we know what the architecture of segregation looks like, I seek to answer how architecture assists with integrating communities of different races, in order to help inform the work of other designers.

Using Singapore as a case study, I investigate how the architectural typologies and urban planning strategies of the nation assist in creating diverse and harmonious communities.

Singapore has adapted its pre-colonial vernacular architecture into modern high-rise public housing that is able to maintain the unique culture of its people. When paired with the Ethnic Integration Policy that ensures homogeneous racial diversity and distribution, we see that Singapore implements integration through close, daily interactions between different ethnic groups. The significance of this study is that it creates an architectural and planning guidebook for the city of Singapore, distilling key design and planning principles that inform how we can create naturally bonding, tolerant and diverse communities.

Background – Segregative Architecture

The history of architecture as a tool for racial segregation is extensive, segregative architecture was practiced widely in the Jim Crow era of racial segregation in order to keep the whites and African-Americans apart. Architecture was used as an instrument of a set of racially segregative strategies. These strategies are broadly categorized as isolation and partitioning. (Weyeneth, 2005)

Isolating strategies focused on keeping races away from one another in their daily lives, specifically through exclusion (the prohibition of African-Americans from using specific places), duplication (separate self-standing facilities for African-Americans that replicates existing white facilities), and temporal segregation (allowing access to certain spaces based on the time of day, or certain dates in the year) (Weyeneth, 2005). When a degree of racial mixing was unavoidable, contact was carefully managed through the use of fixed and malleable partitions. Fixed partitions are a clear boundary denoting white/black space, through architectural examples such as separate entrances to separate interiors, or immaterial boundaries such as at the Chicago swimming beach in 1919.

The impact of segregative architecture was immense in perpetuating the enslavement of fellow humans, and remnants of these projects remind us of a dark chapter in design. Notable existing examples include the 8-mile wall in Detroit, which operated to isolate the lower value African-American-owned properties from adjacent white development projects, as well as Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, which was designed to keep slavery hidden in its walls. These examples show the fearsome power of architecture to segregate and divide, which naturally raises the question: What is the opposite?

Racism

In order to find and understand integrative architecture, a robust knowledge of racism is necessary. Defined as “prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against a person or people on the basis of their membership in a particular racial or ethnic group, typically one that is a minority or marginalized”, racism has always been a pervasive problem in society (Culotta, 2012). While racism can breed through a long history of discrimination, the root cause of racism is the focus of this thesis.

Researchers have explored racism for a good half of the last century, honing in on why multiple global conflicts are based on tensions between opposing races, religions and ethnicities. This research suggests that human prejudice is based in what is called “ingroup love and outgroup hate”, a theory rooted in group and evolutionary psychology (Culotta, 2012). Since the inception of humans as a hunter-gatherer species, humans have cooperated with one another in groups to buffer the individual against the environment (Culotta, 2012). The formation of these ingroups defines a less privileged outgroup, which becomes a competitor for resources or territory, possibly escalating into hostility (Culotta, 2012). The reverse of this theory is also argued, in that hostilities between groups fosters ingroup love since groups that cooperate better win battles (Culotta, 2012).

This bias towards ingroups/outgroups has been proven through the Implicit Associations Test, which asks people to rapidly categorize objects and faces, finding that “it takes significantly longer to associate your ingroup with bad things and the outgroup with good things” (Culotta, 2012). These associations are triggered through heuristics in stressful or tense situations, causing people to jump to discriminatory behaviors and conclusions. lessening opportunities for heuristical conclusions that may be discriminatory.

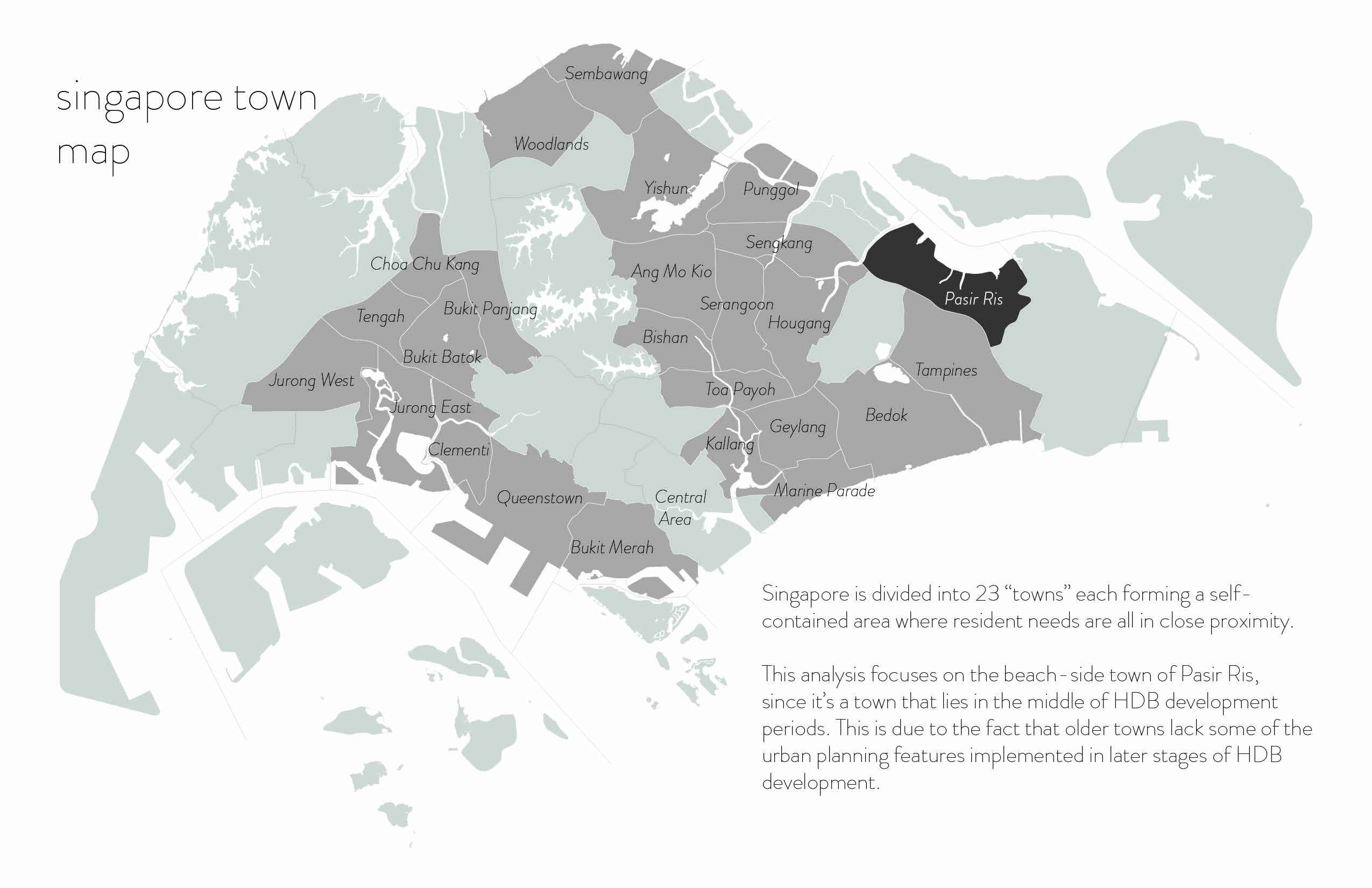

Case Study – Singapore

Ranked highly in terms of racial equity, Singapore is the subject of this integrative architectural analysis. The country’s highly diverse population and high level of racial tolerance, alongside the use of urban planning and architecture to integrate races, makes it a prime candidate for this study.

In order to understand how integrative architecture functions in Singapore, context is required. The small tropical country started off as a home to the indigenous Malay people of the area until it was colonized by the British in 1824. The country eventually gained independence in 1963 after the population lost faith in the British after their failure to defend Singapore during WWII. Over time, the country was settled by the neighboring Chinese and Indian populations, forming the country’s current demographic of Chinese (76%), Malay (15%), Indian (7.5%), and Other (1.5%) (Government of Singapore, 2019). During Singapore’s formative years as an independent nation, race tensions were rife between the Chinese and Malay populations due to an attempted merger between Singapore and Malaysia. These tensions escalated into the 1964 racial riots which ended with 23 dead and 454 injured.

As a means to combat racial tension and civil unrest, the government implemented the Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP) through its public housing system, the Housing Development Board (HDB). Due to Singapore’s small landmass, measuring only 50km x 27km, the Housing Development Board had to develop public housing in a fashion that is sustainable for long-term development. Large portions of Singapore are developed through the Housing Development Board and sold to citizens through 99-year leases which allows for eventual housing redevelopment and turnover. Racial enclaves were common during Singapore’s formative years, which was a factor in creating tensions between races. As a response, the Ethnic Integration Policy limits the sale of public housing to the different races of Singapore through the allotment of quotas in each block and neighborhood. Once a certain racial quota is reached, further sale to people of the same race is prohibited, thus preventing racial enclaves from forming (Harrison, 2019). The EIP also allows for residents to have more opportunities to interact with people of other races in their daily lives, which is in line with the integrative strategy to expand the ingroup of the population. While the EIP works on a policy level, Singapore also enacts four main integrative strategies through its architecture and urban planning.

Integrative Strategies

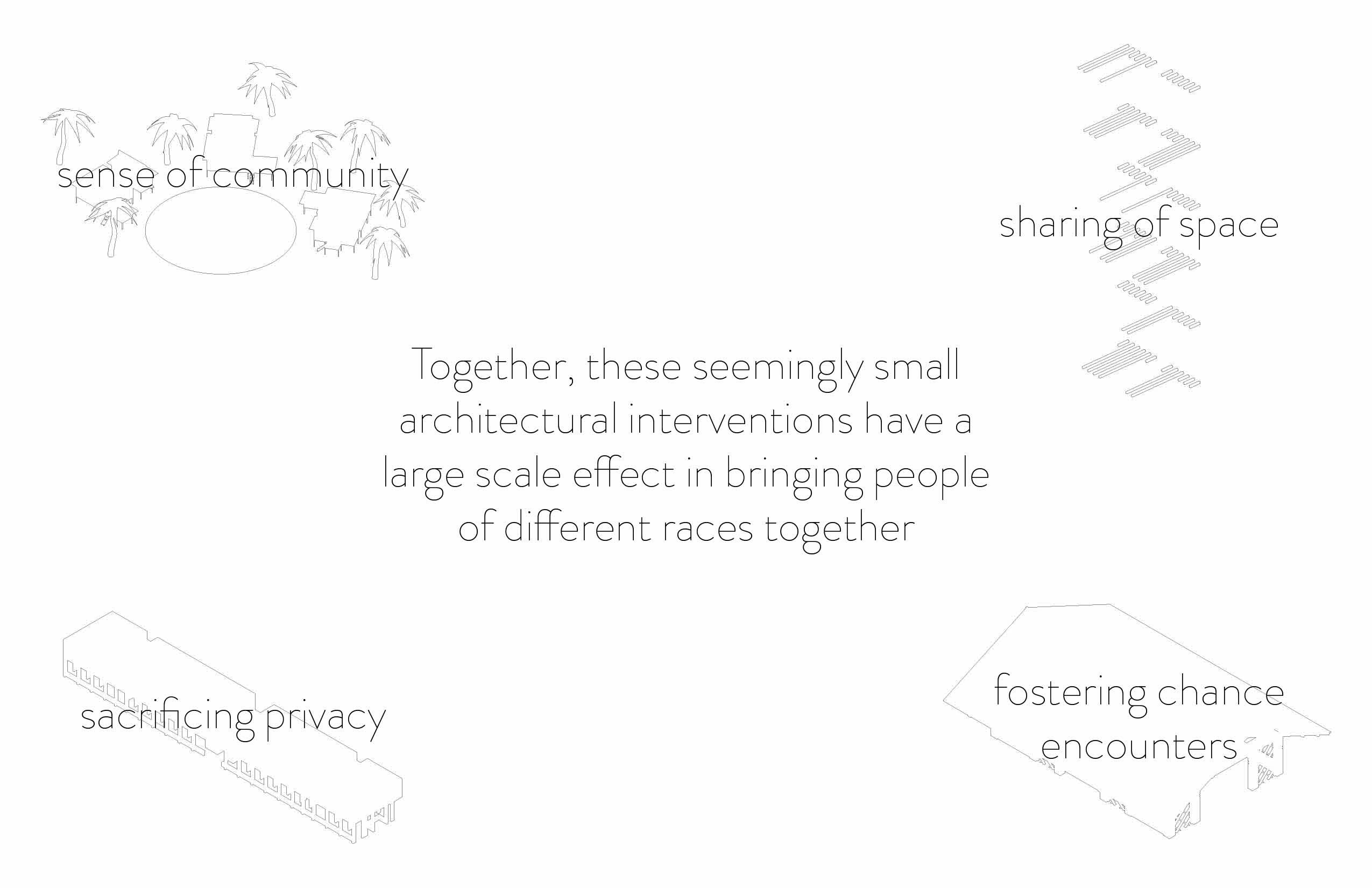

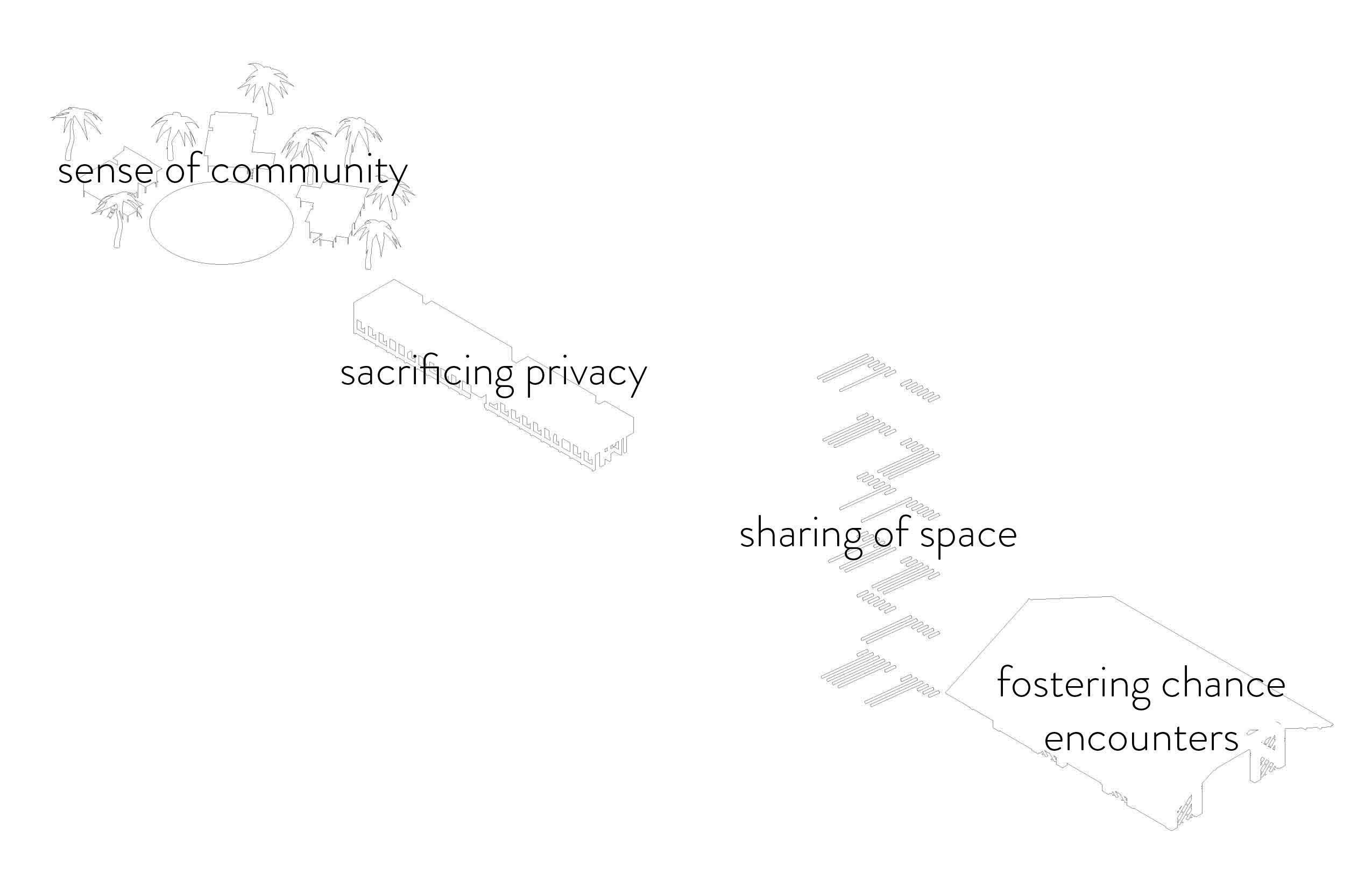

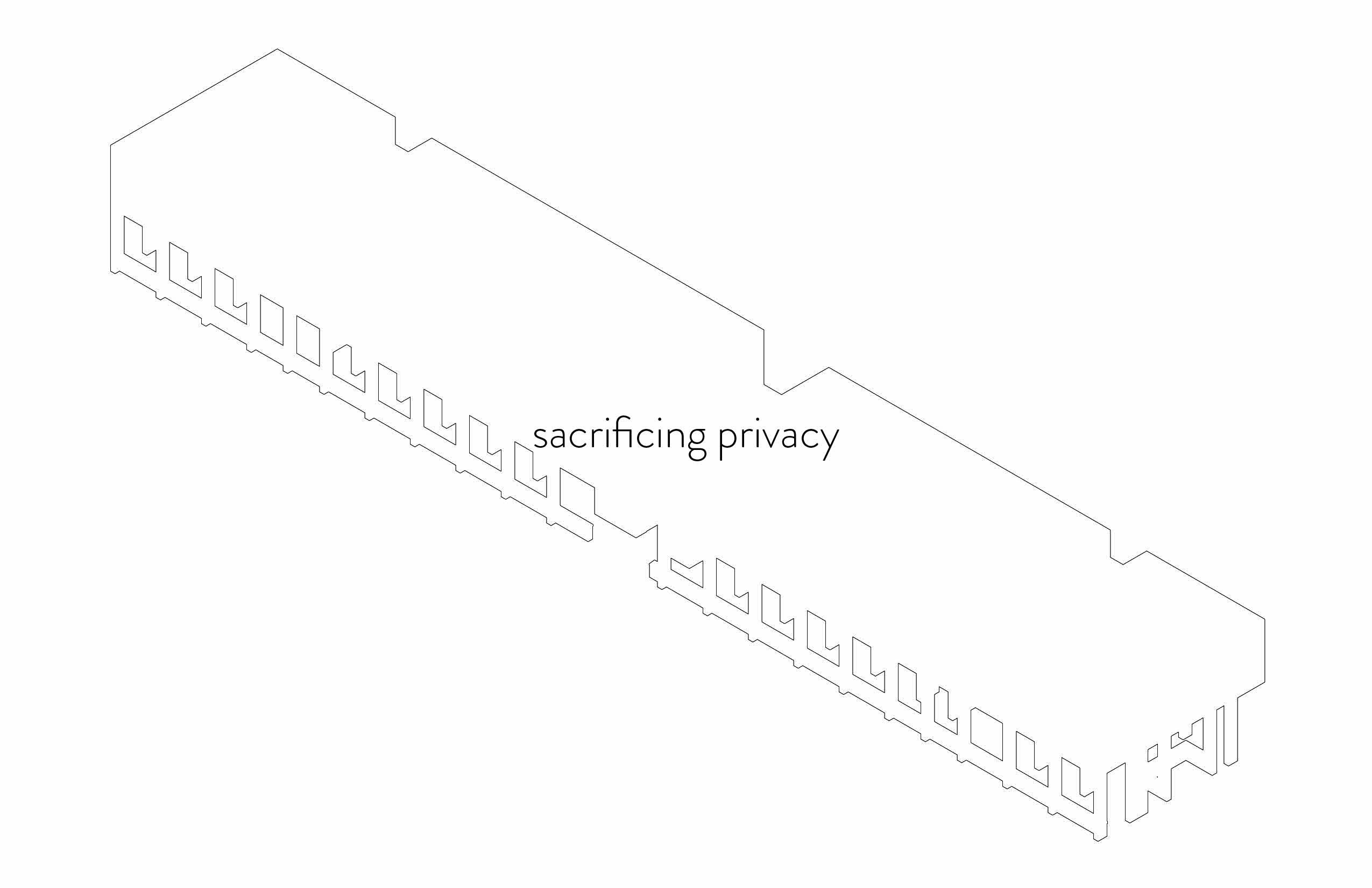

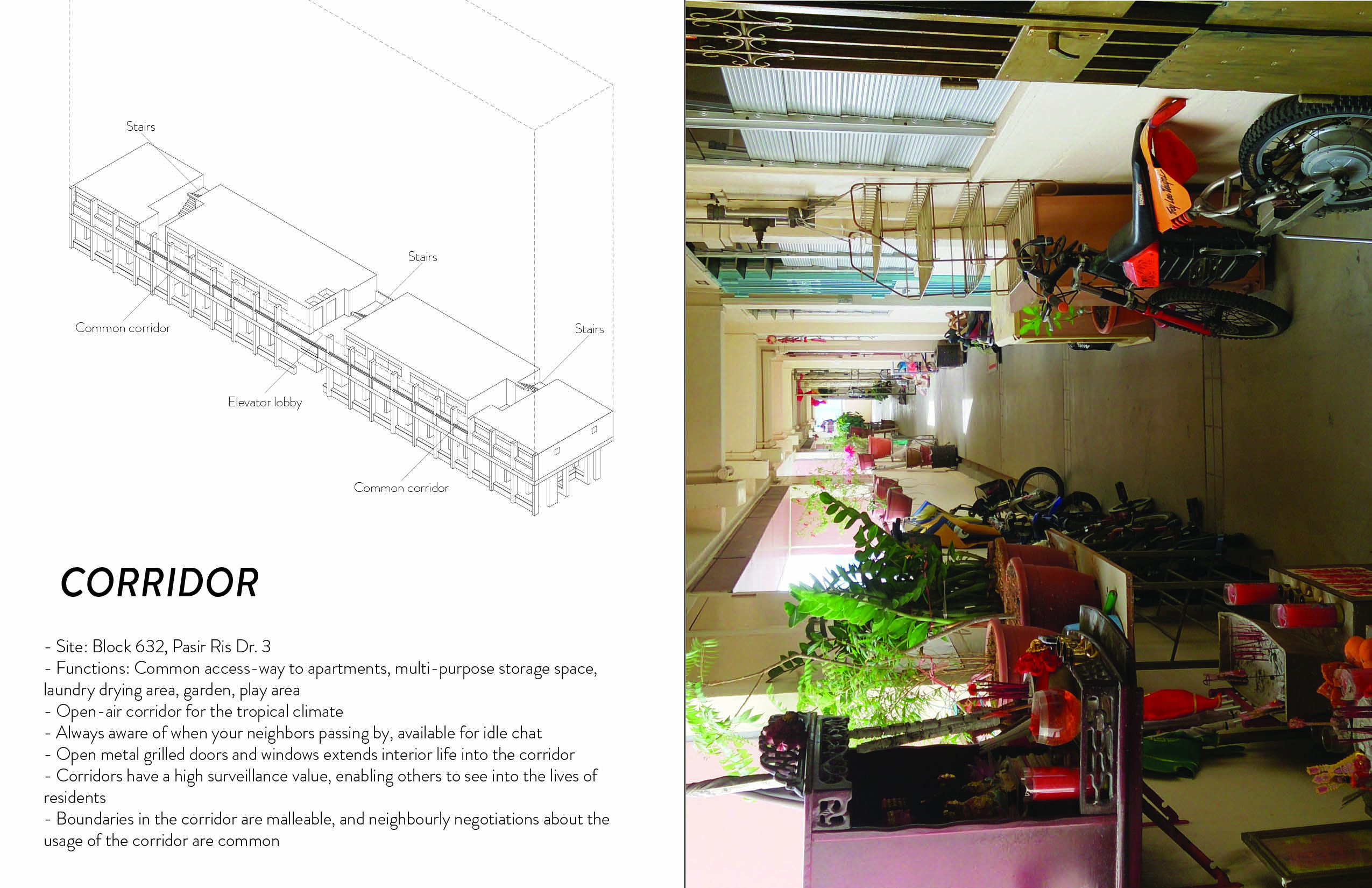

These four main strategies are as follows: Firstly, Singaporean towns, neighbourhoods and precincts are planned with a consistent architectural theme in order to build a sense of community through design. Secondly, linking the open ground plane in public housing precincts allows for multiple chances for interaction between neighbours and community events. Thirdly, Singaporean public housing is designed with a high surveillance value which sacrifices privacy in order to help socialize neighbours. Finally, multiple spaces in Singaporean public housing blocks are shared in order to build tolerance and exposure to different cultures. Together these integrative strategies and the architecture that supports them are documented through this thesis in order to diagram their inner workings. These strategies, while implemented in a top-down fashion by the government, actually have roots in Singapore’s vernacular architecture, which allowed them to become easily accepted by the population.

Vernacular Architecture

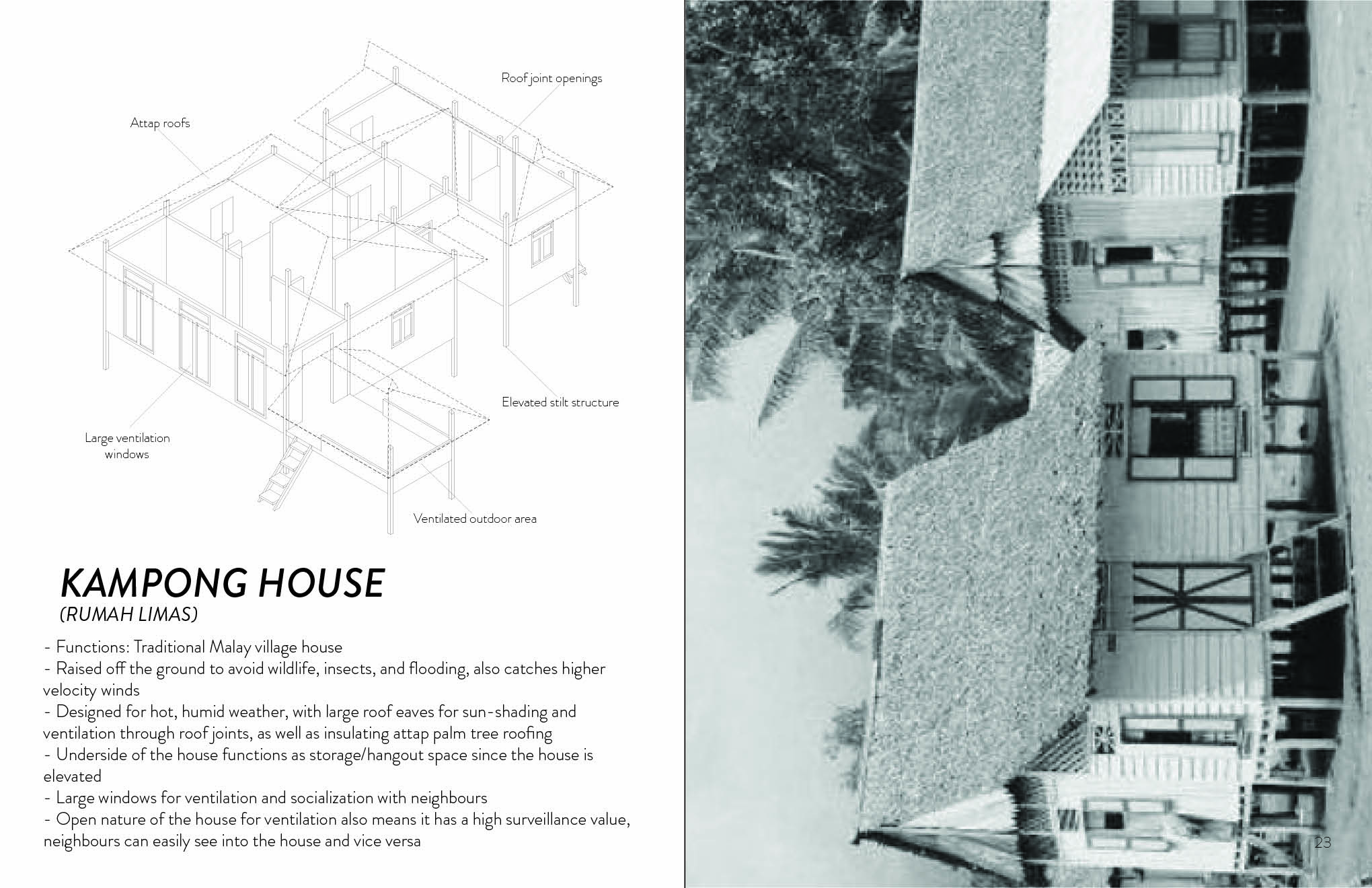

Being a tropical country with a hot and humid climate. Traditional Singaporean vernacular architecture has been adapted for comfortable living. These vernacular houses take the form of single-story bungalows that are raised on stilts, usually built with surrounding hardwood and roofed with leaves from the attap palm tree. The stilts allow these houses to catch higher velocity winds, as well as avoid ground-level pests and flooding. These houses are also usually built with large windows, doors, and roof gaps that allow for greater ventilation. These large windows and doors give these vernacular houses a high surveillance value, meaning that any ongoing activities and conversations are easily overheard by people outside the house. The particularities of this type of housing have been passed onto modern Singaporean public housing typology. Singaporean public housing is similarly elevated on large columns and has apartments that face out into open-air corridors located at the edge of the building. This causes public housing buildings to have the same high surveillance value present in Singaporean vernacular architecture.

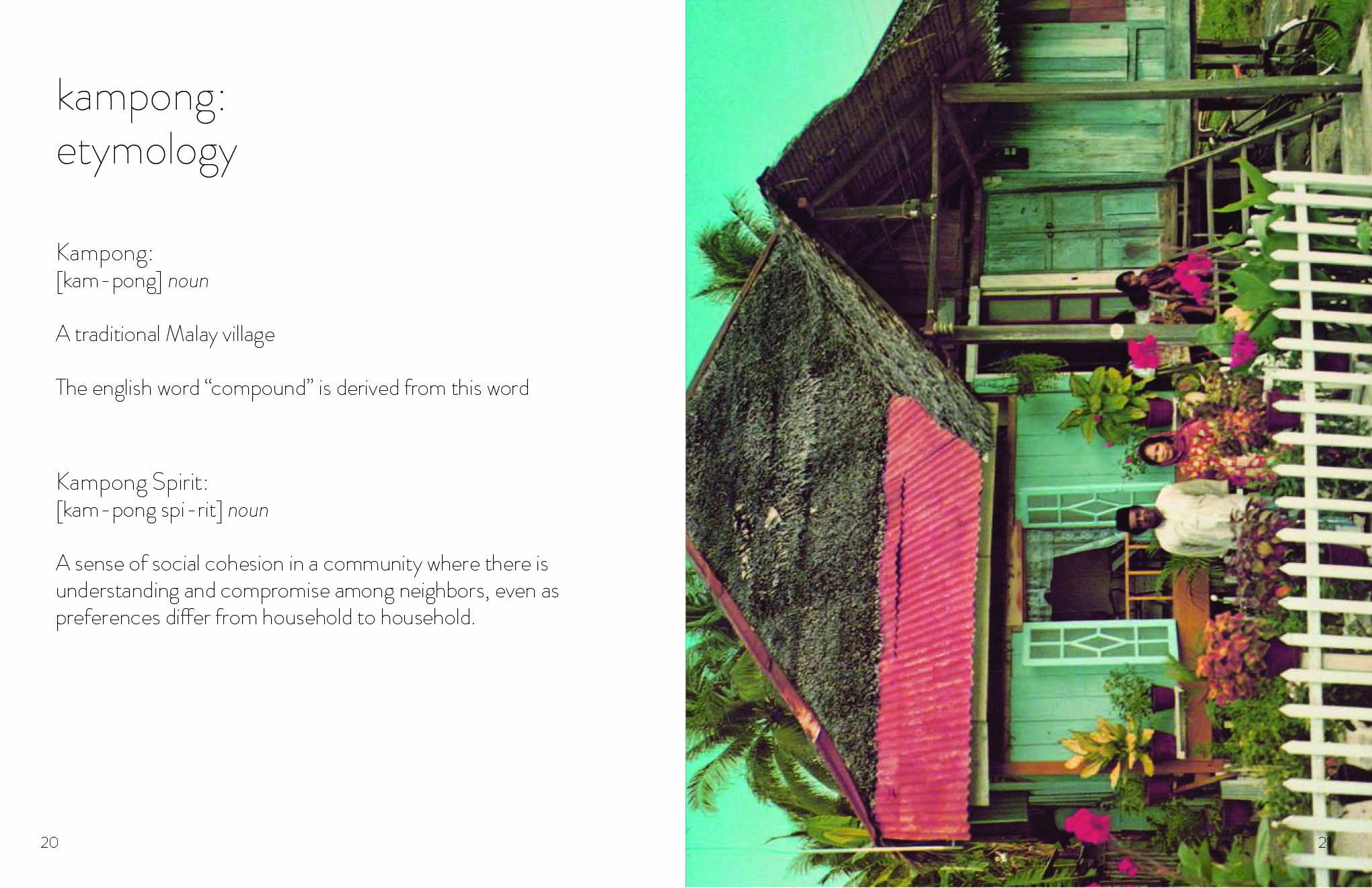

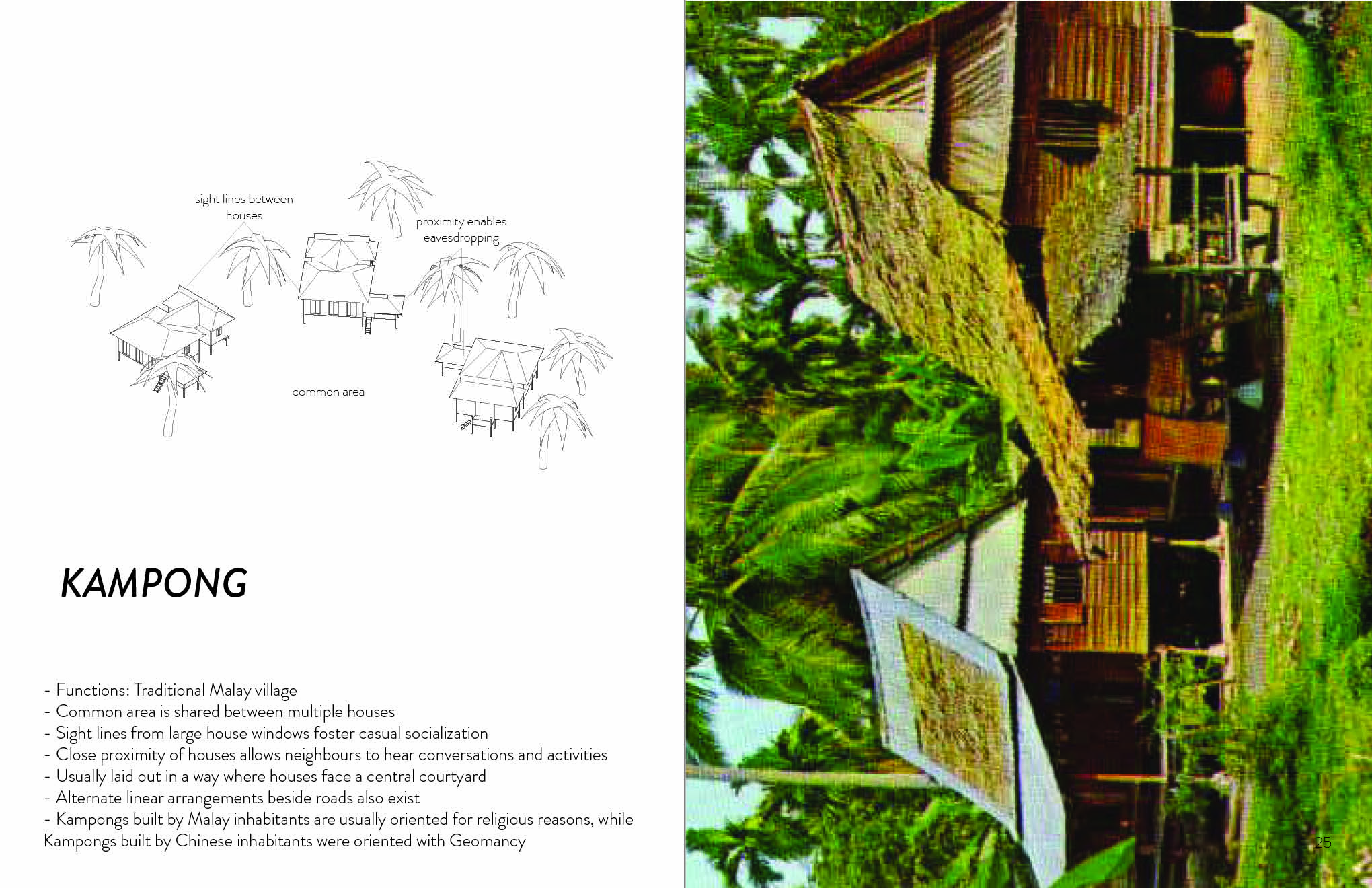

Singaporean vernacular architecture was arranged in communities referred to as “kampongs”, which is the Malay word for “village”. These kampongs featured a shared central space that allows for neighborly interaction and activities. This shared common area assisted in developing what is known as ”kampong spirit” within the kampong. “Kampong spirit”, refers to a sense of community where community members would help one another while practicing understanding and compromise, originating from the hardships of kampong lifestyle (Chia, 2021). The importance of kampongs in the modern architecture of Singapore persists through these themes of community bonding, shared space, and the architectural typology of the kampong house.

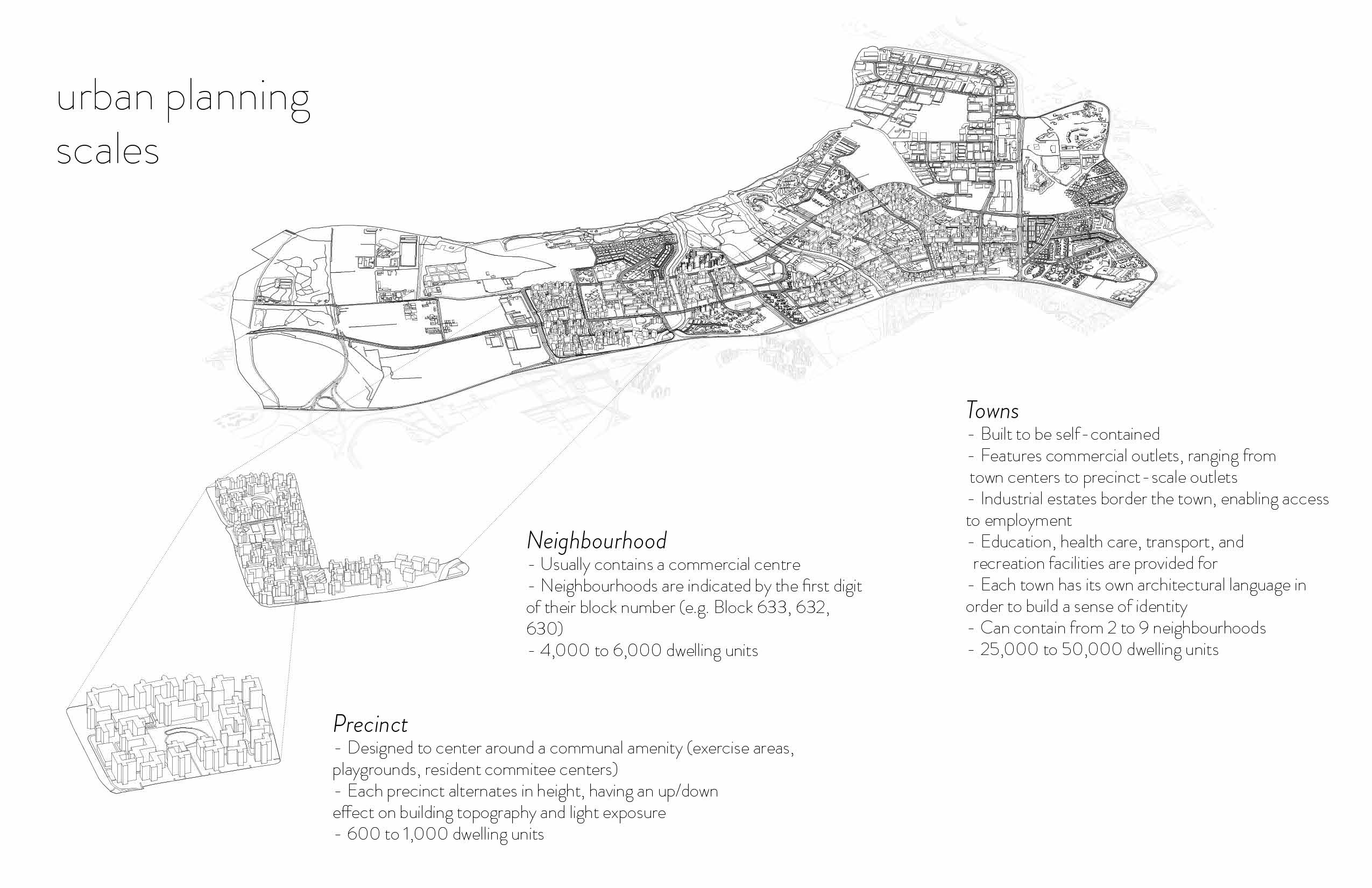

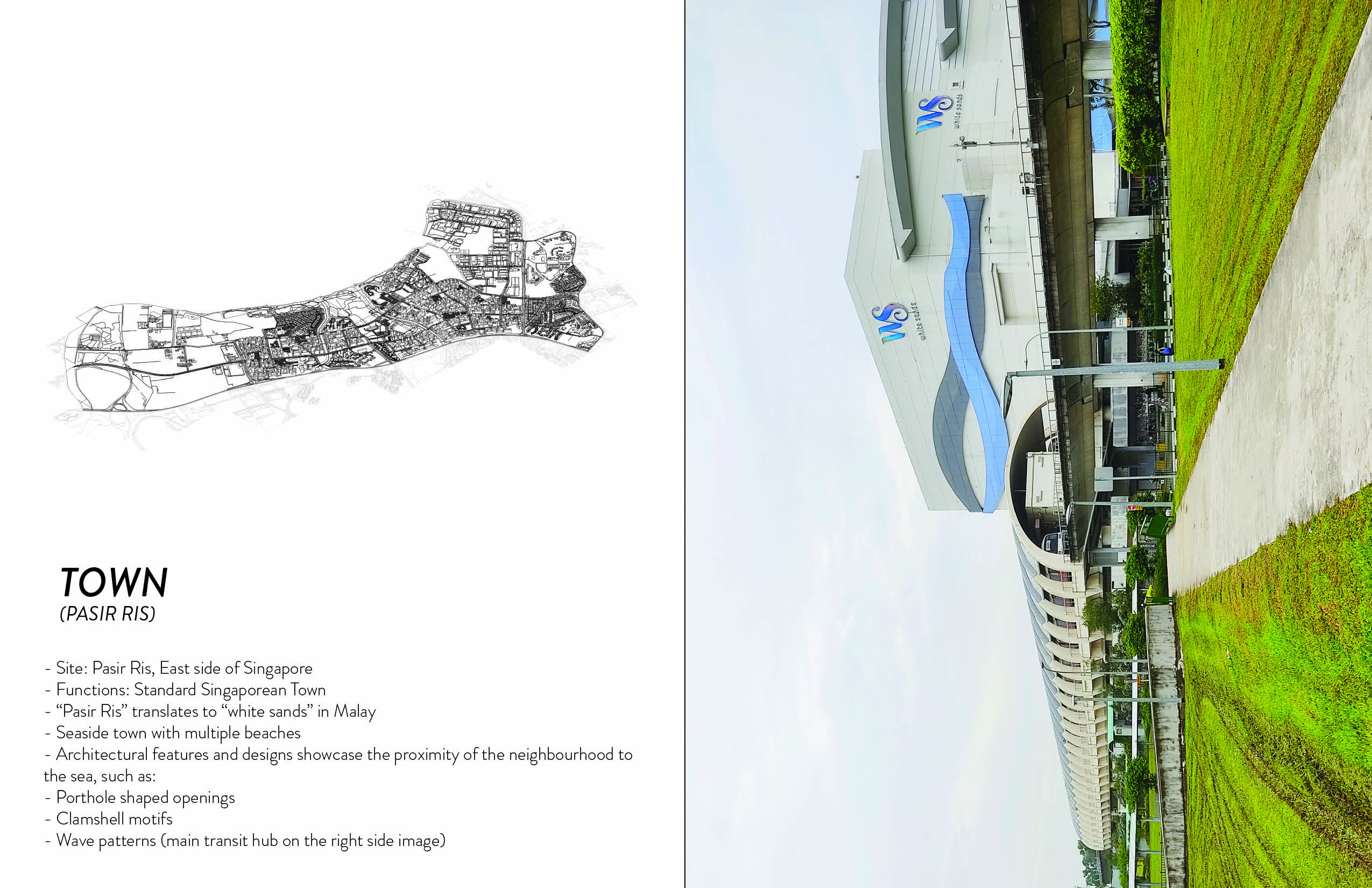

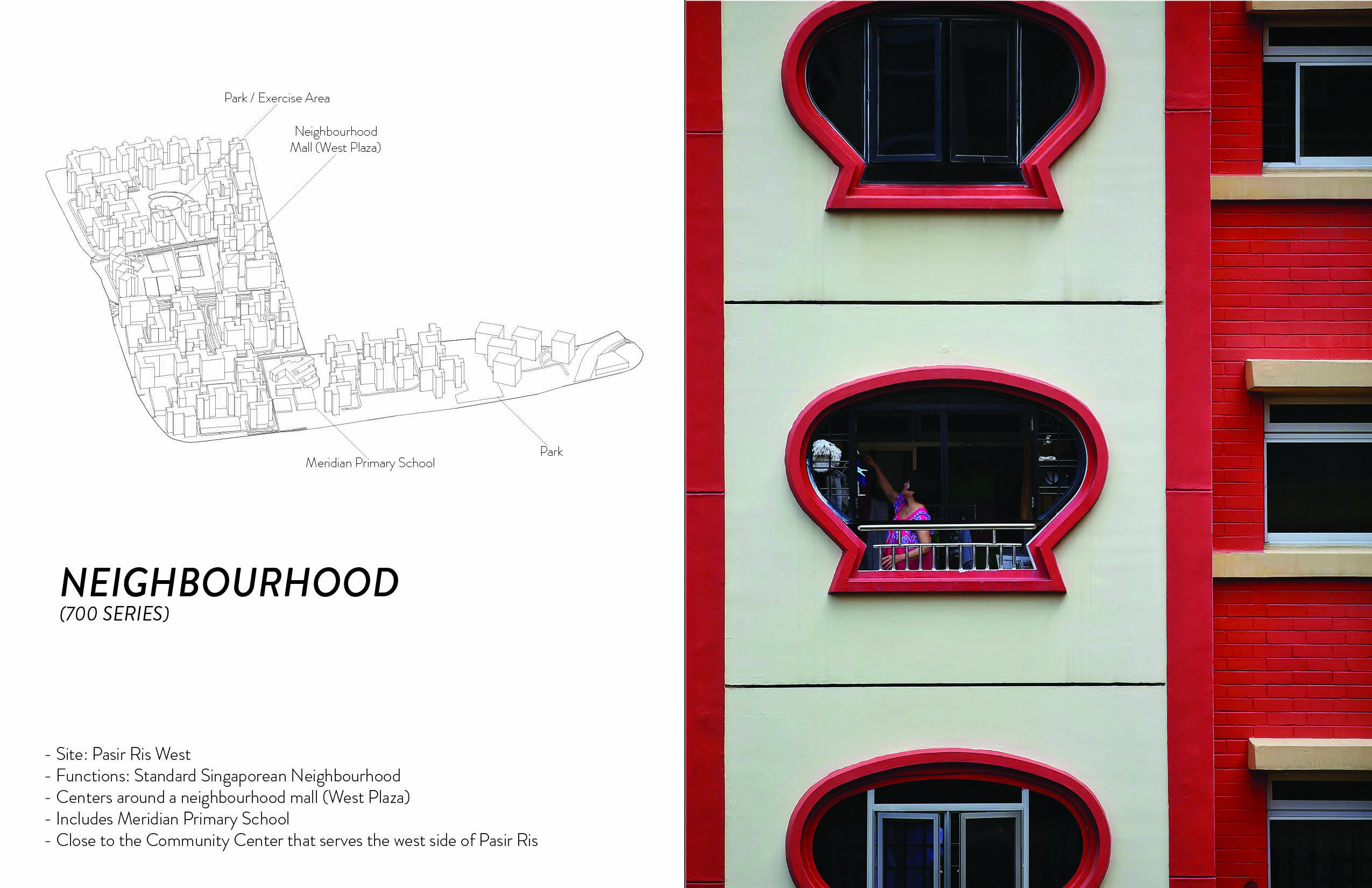

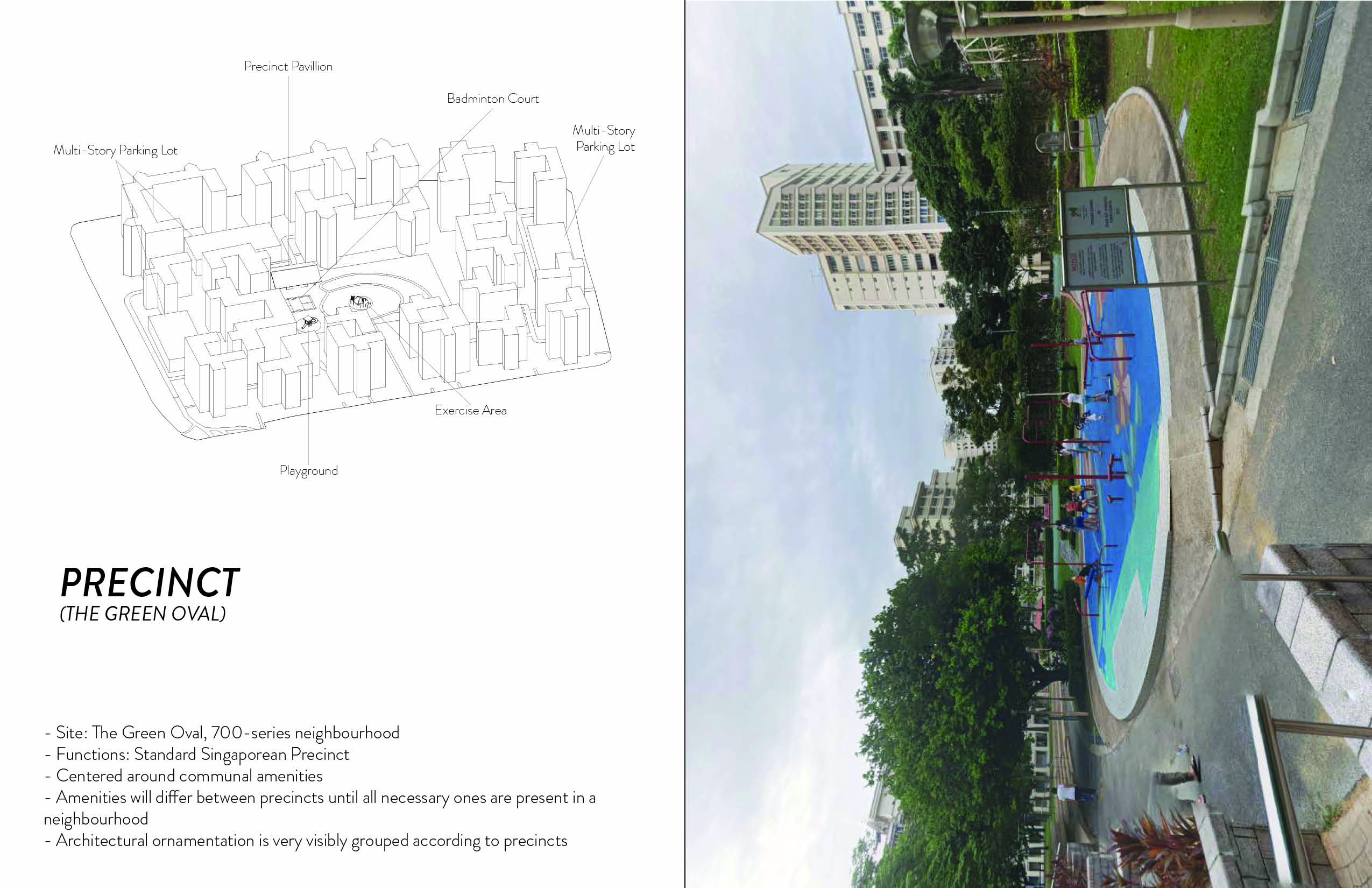

The first of four integration strategies utilized in Singapore pertains to the design of Singapore’s public housing buildings at a large scale. Urban planning in Singapore is divided into three distinct scales, the town, neighborhood, and precinct. The town refers to a large district area of Singapore that is developed by the Housing Development Board for public housing. Built to be self-sufficient, these planned town areas include most communal facilities and amenities required for daily life, including transportation, recreation, healthcare, education, employment, and industrial facilities. Architecturally, these towns are designed with unique ornamentation and patterns reminiscent of their history or location. Towns such as “Pasir Ris”, which translates to “White Sands” in Malay, features wave motifs, porthole windows, and other designs representative of their location (Housing & Development Board, 2021). Other town examples include “Bishan”, named and designed after the Cantonese cemetery which once occupied the area, with pitched roofs and linkway structures, as well as “Choa Chu Kang”, derived from the Teochew word “Kang Chu” meaning “River Clan”, designed with a rural theme harking back to its roots as a plantation (Housing & Development Board, 2021). These towns usually house somewhere from 25,000 to 50,000 dwelling units, and include anywhere from 2 to 9 neighbourhoods. These neighbourhoods include around 4,000 to 6,000 units, and are generally centered around a mall that serves the community’s daily needs. These neighbourhoods are identified through the first digit in their three digit block numbers e.g. 633, 632, 630 belong to a single neighbourhood. The neighbourhoods are further divided into precincts that house 600 to 1,000 dwelling units. These precincts are where a specific sense of identity with the community is developed through a cohesive architectural style specific to that precinct. Newer precincts now include a precinct name in order to further add to that sense of identity.

The use of policy like the EIP to ensure a homogenous spread of races assists in building a sense of community by preventing the identification of a neighbourhood by its racial makeup. While the implementation of a consistent and unique architectural language in towns and precincts allows for residents to identify with the community through its architectural qualities, building a sense of community (Peggy, 1996).

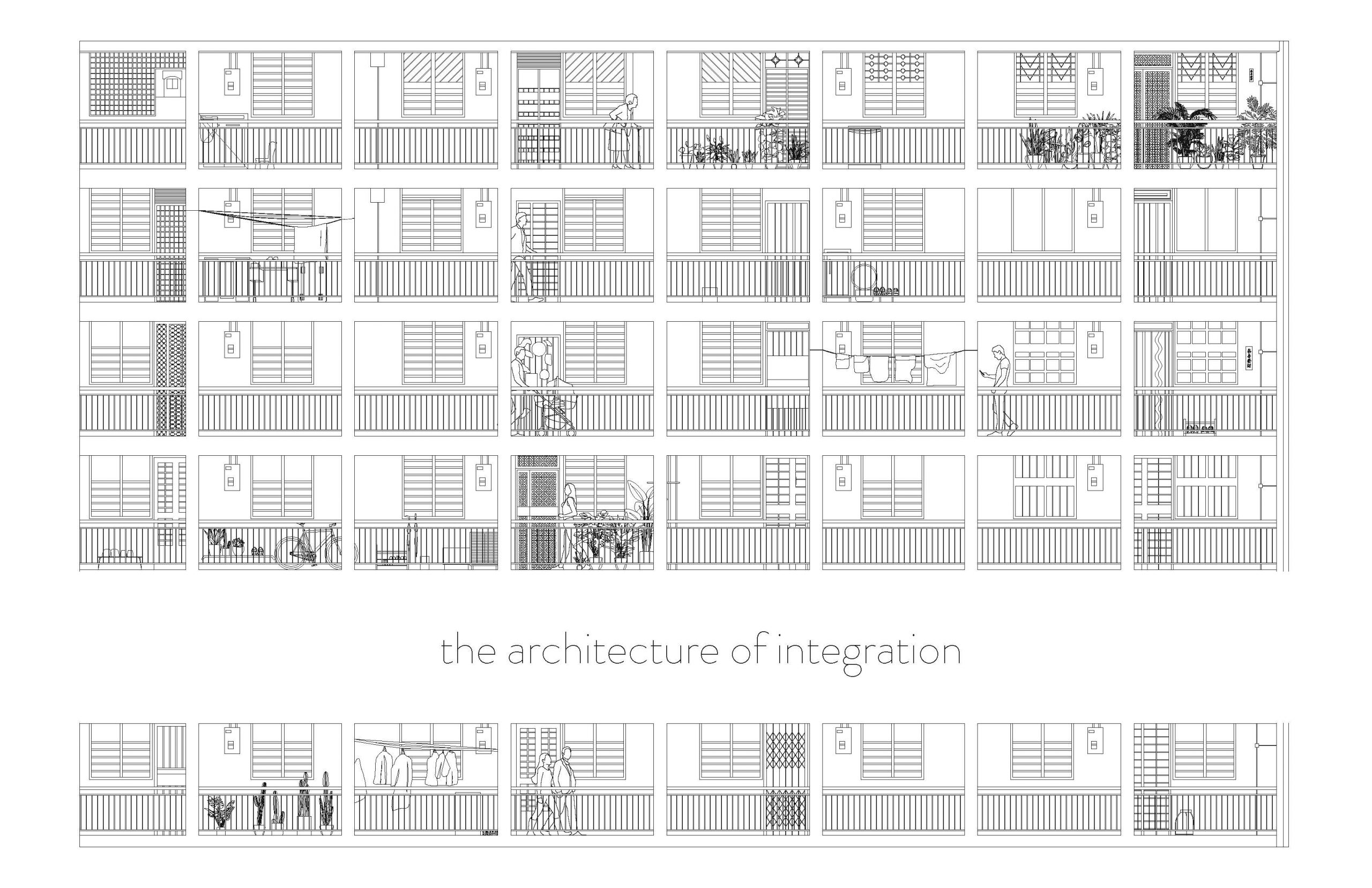

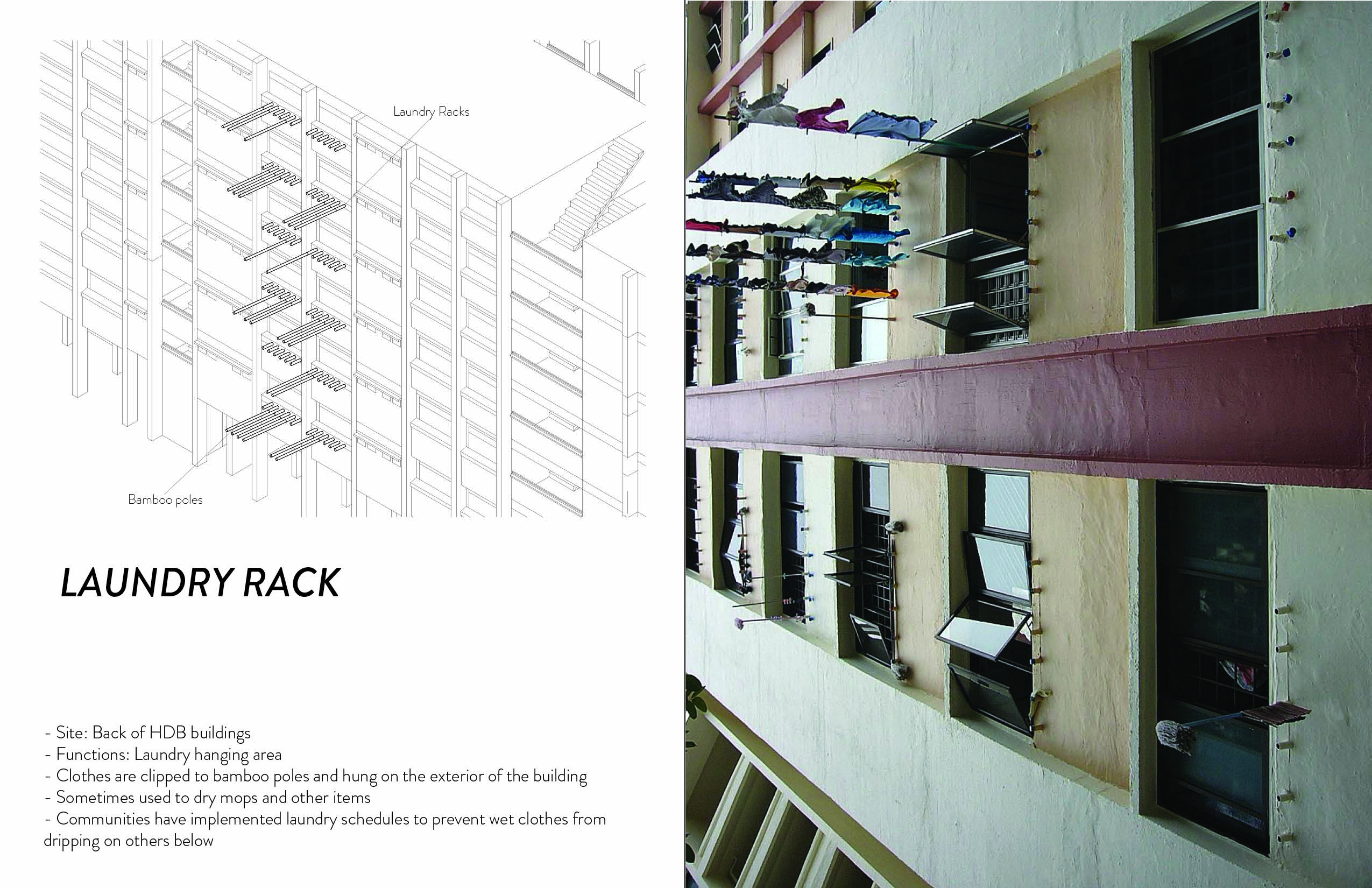

The second of four integrative strategies utilizes the high surveillance value passed down from Singaporean vernacular architecture. The outwards facing doors and windows allow for easy visual and oral access to the interiors of the flats and vice versa. Passing neighbours are able to easily identify interior activities in passing, and thereby get a sense of who their neighbours are and what kind of activities they participate in. This involuntary socialization with neighbours is an important aspect of public housing in Singapore, allowing neighbours to gain a sense of understanding without even consciously acknowledging each other. The corridor in Singapore is also used as an informal storage space, often storing items such as shoes, bikes, plants and religious shrines/offerings. This shared storage space allows for neighbours to gain a further understanding of one another involuntarily, and slowly helps build a tolerance towards unfamiliar cultures. Items that are often troublesome, such as incense offerings which produce ash and a strong scent, can gain familiarity and eventually become wholly accepted by neighbours.

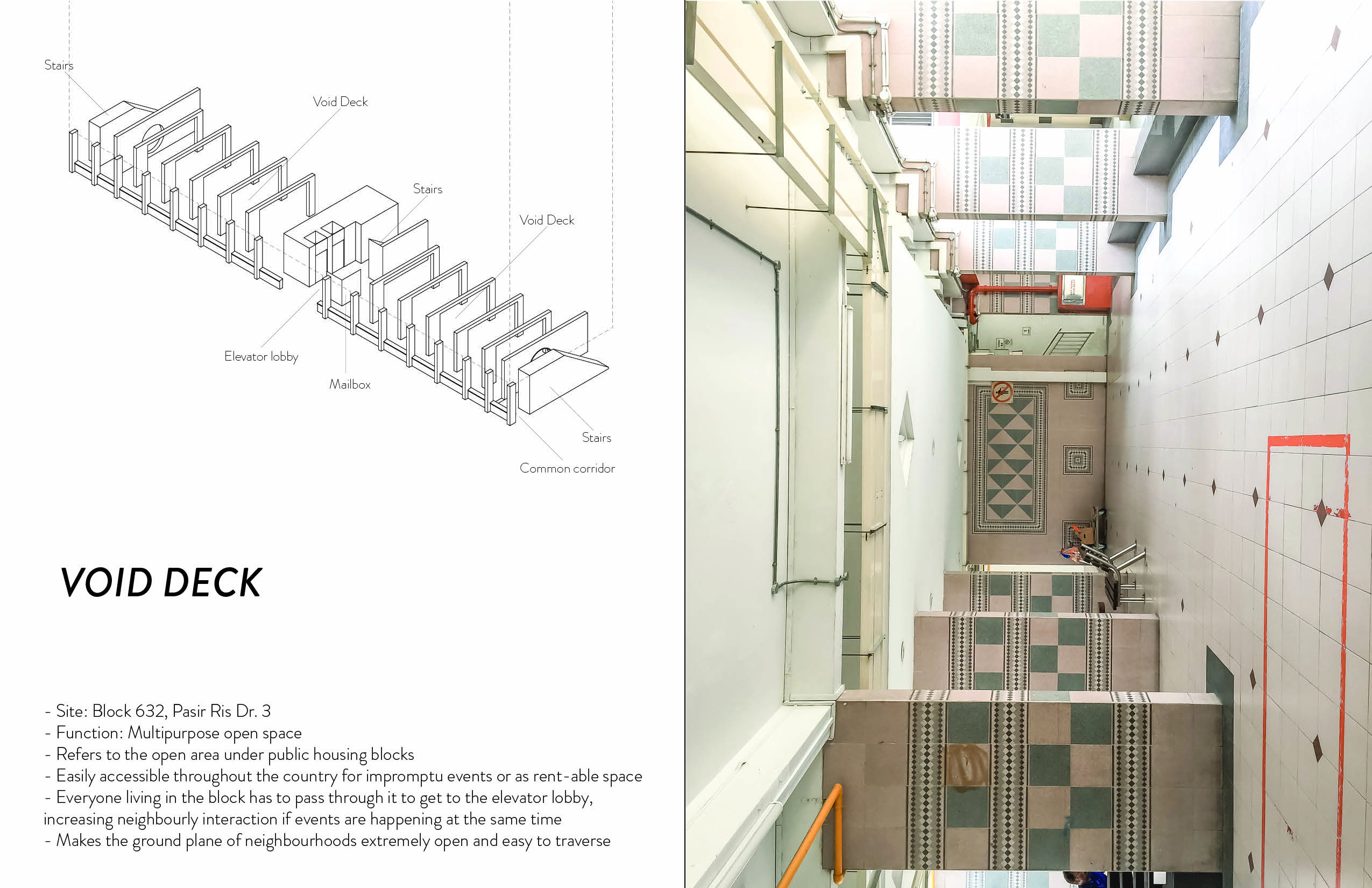

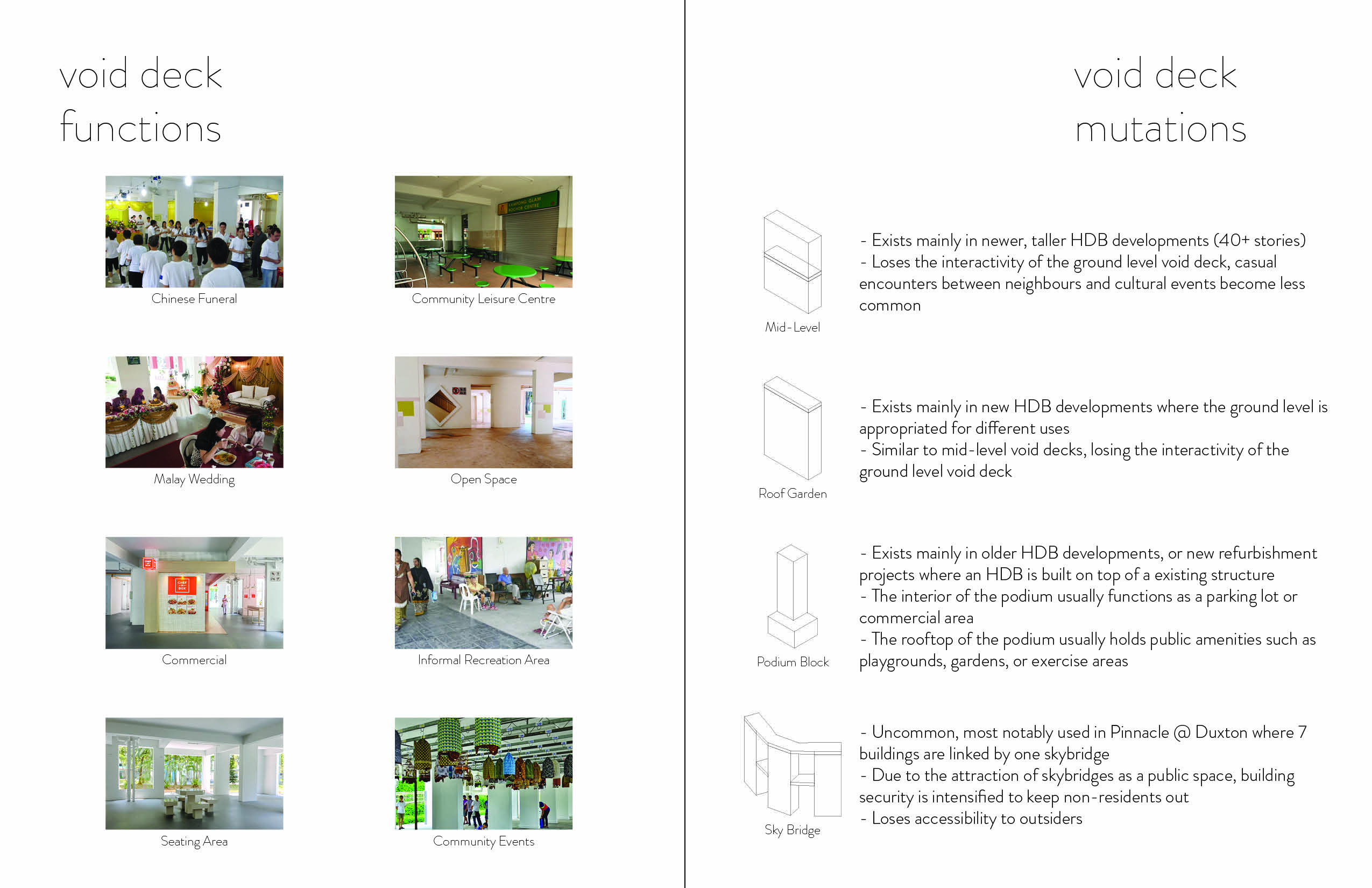

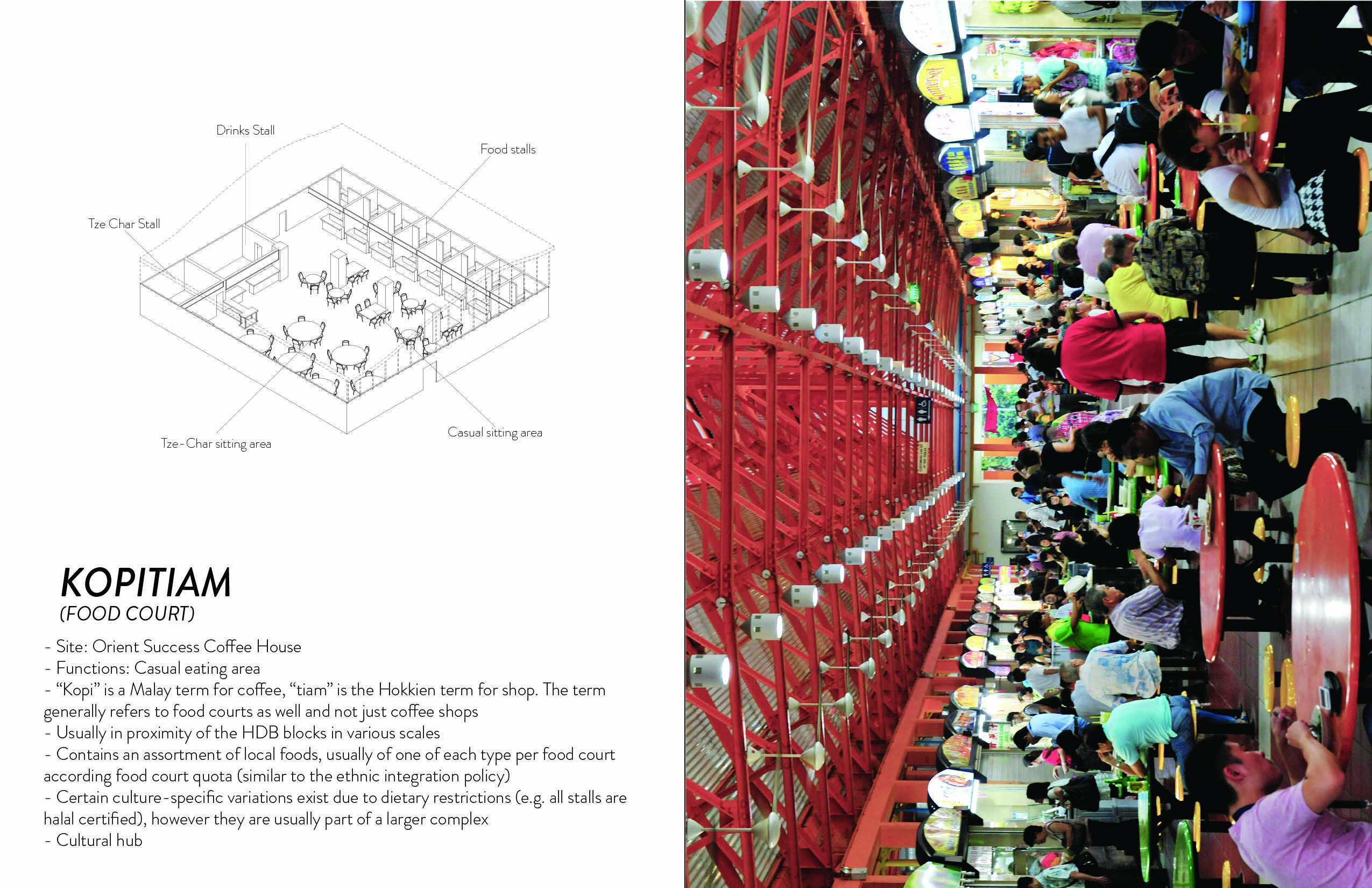

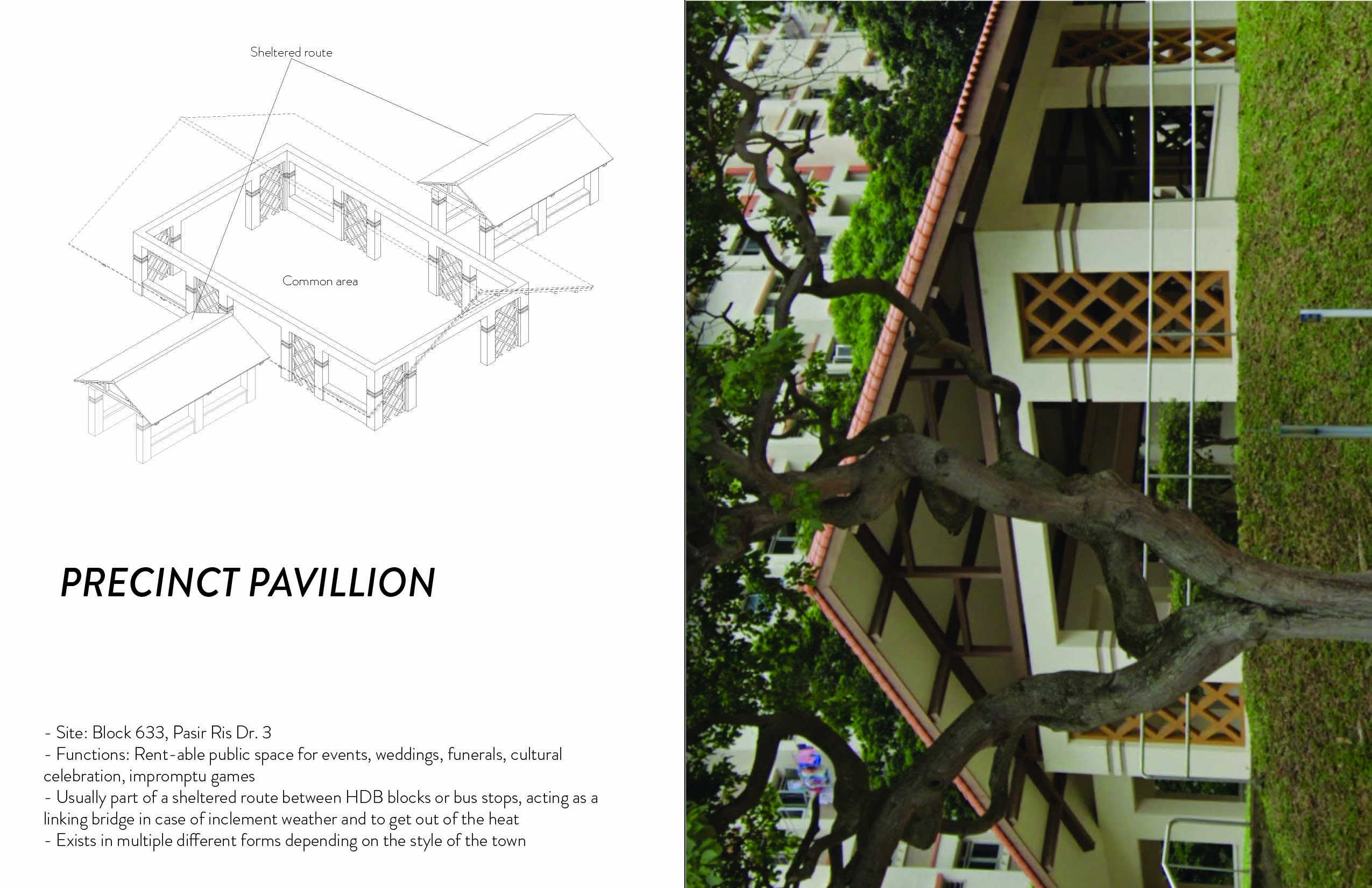

Similar to how corridors are shared spaces that provide clues to the lives of inhabitants, many typologies exist in Singaporean public housing as a way for residents to share their day-to-day lives with one another. The third integrative strategy is based on using proximity and accessibility to shared common spaces in precincts to foster tolerance, acceptance, and understanding for other races and cultures. Since public housing blocks in Singapore are raised on columns creating an open ground plane much like its vernacular predecessor, the open area is easily accessible to residents and passersby. This open area is referred to as the “void deck”, hosting a variety of different functions such as weddings, funerals, community events, and community leisure centers. The void deck is often fitted with different amenities and furniture like stone/concrete benches and tables. It is also sometimes furnished with resident donated furniture, forming an informal recreation area. The void deck also commonly finds itself a host for impromptu events such as children’s soccer games. This unique typology is immensely important to racial integration in Singapore since it provides the opportunity for casual exposure to cultural events, especially through its wide availability throughout public housing projects in the nation.

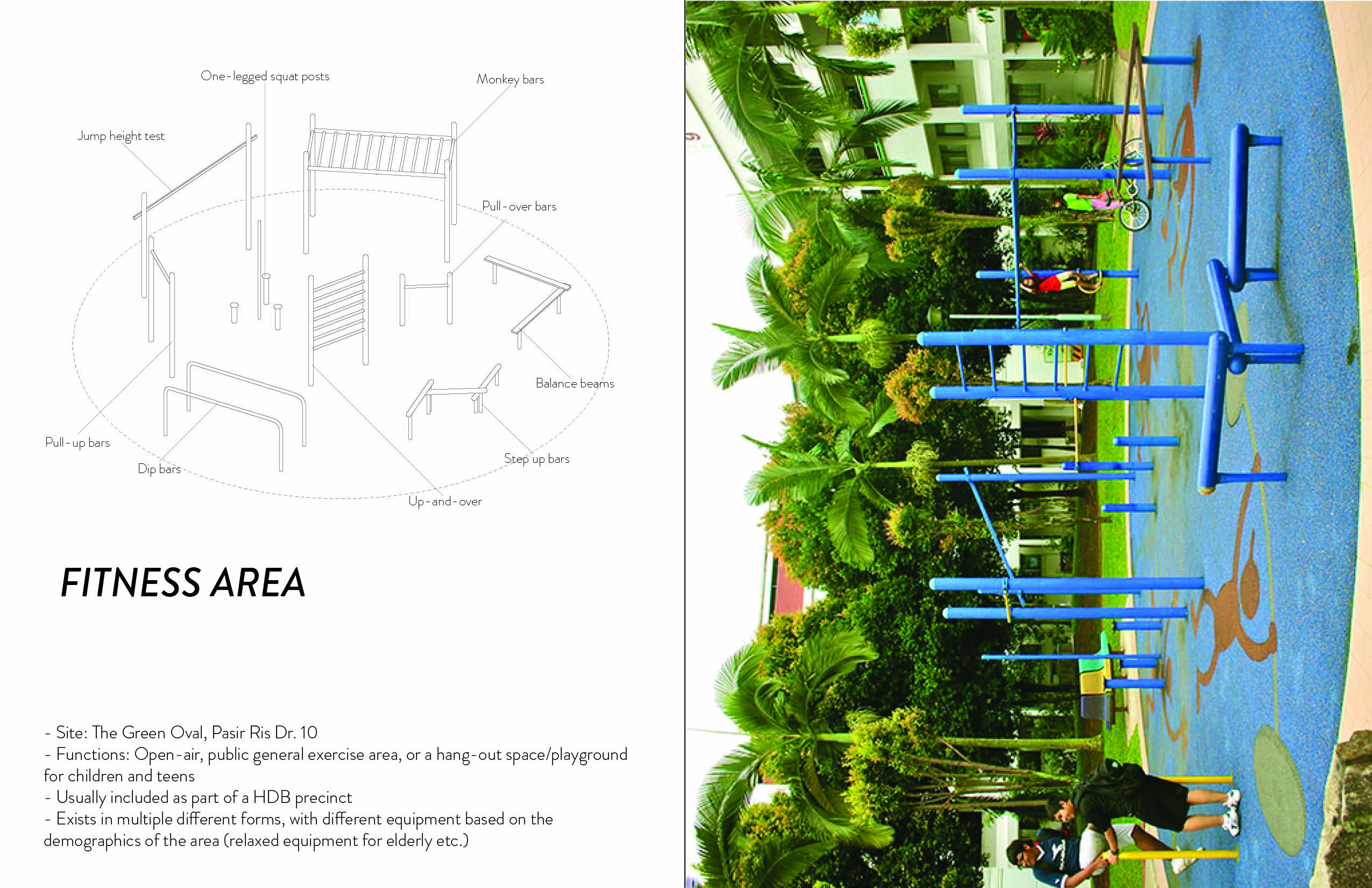

Sharing space with other people is not easy and many times conflicts arise due to differences in culture, habits, values and perspectives. However, the nature of our world is that all space is shared, and co-existence is a must. These examples of space sharing in Singapore are a way integration is built into daily life, where through close contact, residents learn about one another’s cultures and to be tolerant of those they don’t understand. Alongside void decks, these other typologies help integrate residents:

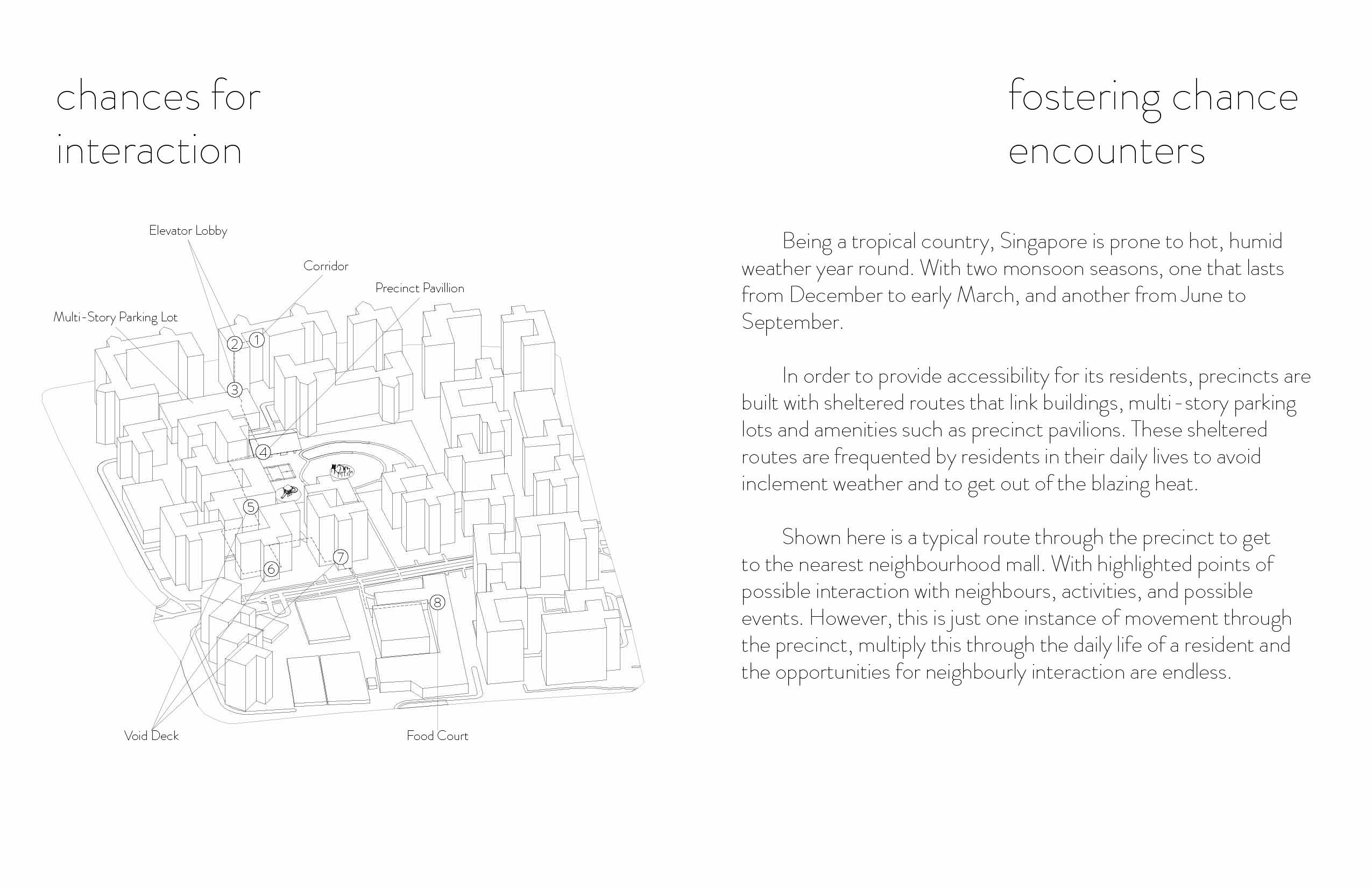

The fourth integrative strategy takes advantage of the prevalence of shared space throughout public housing precincts in the city. Through a system of connected sheltered walkways throughout the precinct, residents can traverse their precincts without exposure to the hot sun or inclement weather local to the equatorial region. These sheltered routes utilize previously mentioned elements such as void decks to link the precinct together and also include a new typology of the precinct pavilion, a rentable, shared open space that occupies a space independent of any building. These precinct pavilions operate as nodes in the route, connecting multiple different routes together. As such, they are able to expose passersby to any ongoing events or activities, in the same way the void deck does. Together, this sheltered route on the ground plane of precincts offers multiple points of possible interaction with neighbours, activities and community events. Multiply this by the daily life of the countless residents staying within the precinct, and suddenly the opportunities for neighbourly interaction are endless.

Adapted from its village community based vernacular architecture, Singapore’s public housing system has implemented these four racial integration strategies to great effect. By creating a sense of community through design, residents are more likely to identify their neighbourhood through architecture instead of race. HDB corridors provide a high surveillance value, sacrificing privacy in order to get to know surrounding neighbours. Multiple avenues of shared space ensure that chances for cultural exchange and interaction are rife. While careful urban planning and the linking of the ground plane fosters endless chances for interaction in the neighbourhood. Together, these micro-scale interventions have a macro-scale effect on the community. Bringing people together in their daily lives, expanding friend groups and building tolerance and respect for other cultures.

Although these strategies have worked well for Singapore, many of them are context-specific. Adaptations of vernacular kampong architecture would be poorly suited for other climate regions, and different cultures may not use open spaces in similar manners. Regardless, the base principle that these strategies operate on is the same. Getting to know people from different races and cultures in daily life allows the population to increase its tolerance and acceptance for others, thus integrating and expanding the ingroup of residents.