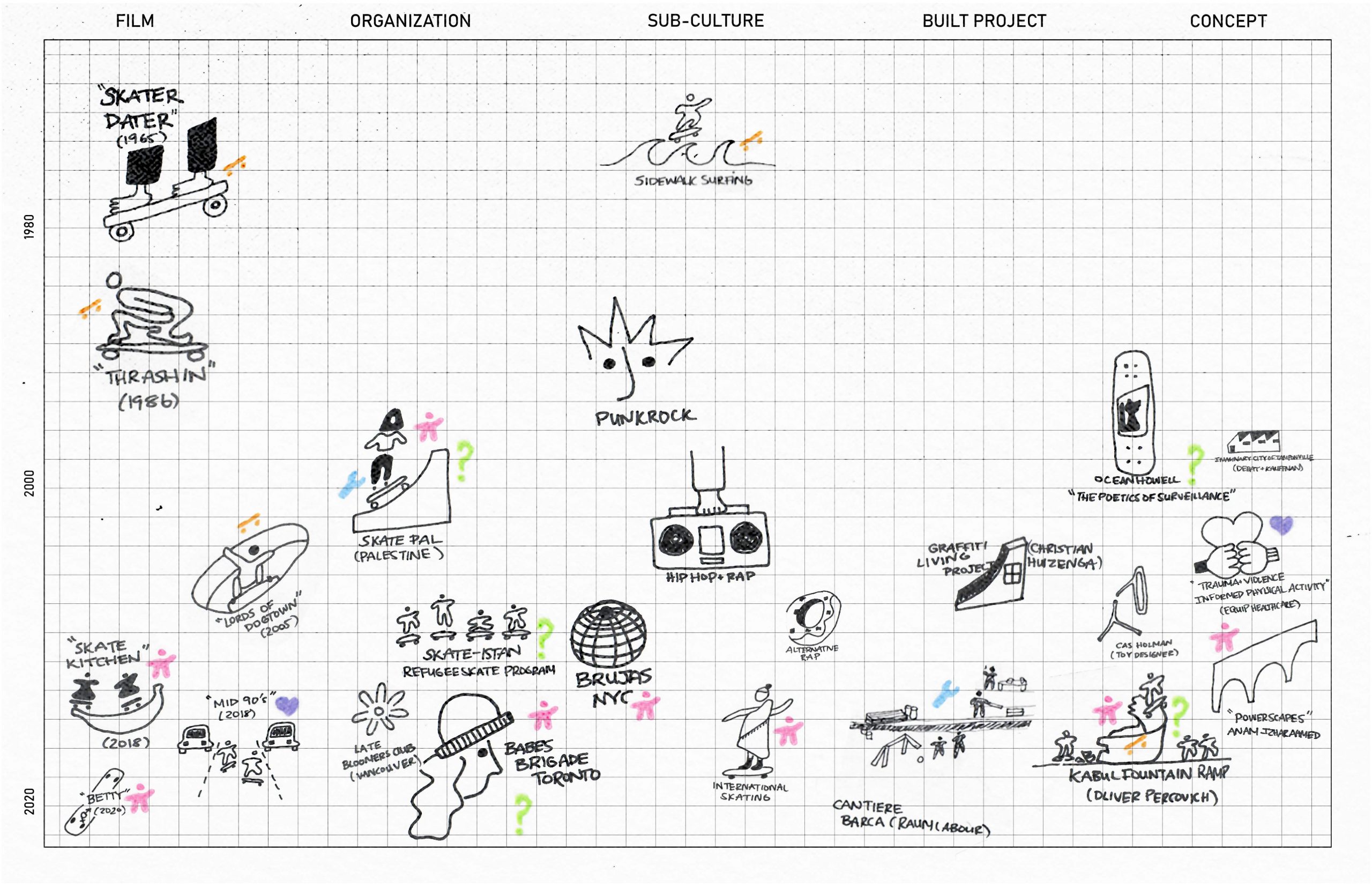

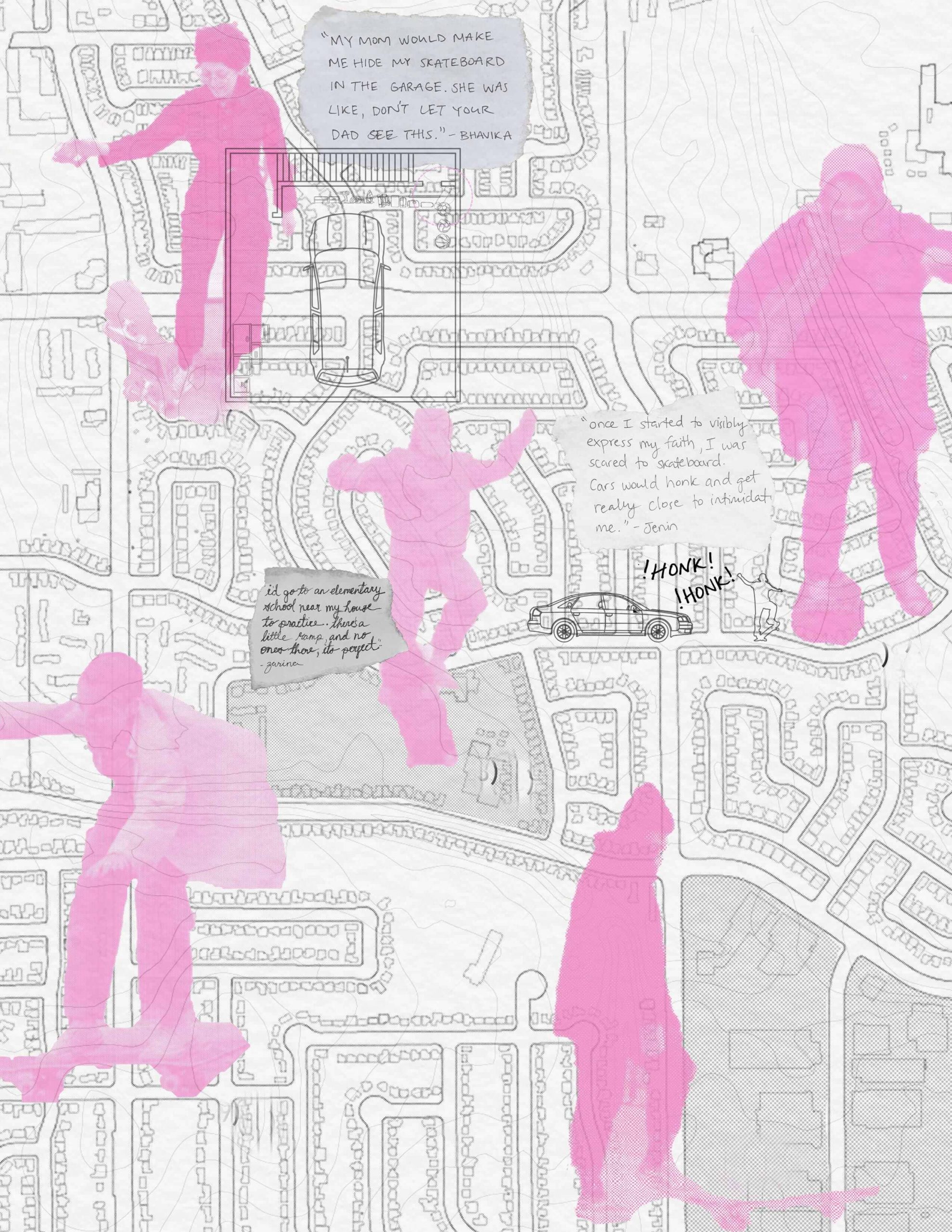

Research and interviews were done in order to obtain first hand stories of how individuals experience and appropriate the environments they occupy. The goal of this process was to gain a unique perspective about public spaces through the lens of non-traditional skateboarders.

Excerpts from interviews conducted

How does gender and religion affect your skating experience?

Soummaya: A lot of girls have problems with their parents, because of their gender. It’s like, “why are you doing this, people are gonna think of you differently”. And people are gonna think of you as this outgoing girl, they think you’re like a slut or something. I’m like, what does that have to do with anything? My dad was very strict and stuff. I didn’t know if he was gonna be like, “you can’t be doing this”, but then I just kind of did it anyways.

Describe your relationship with the neighbourhood you skate in.

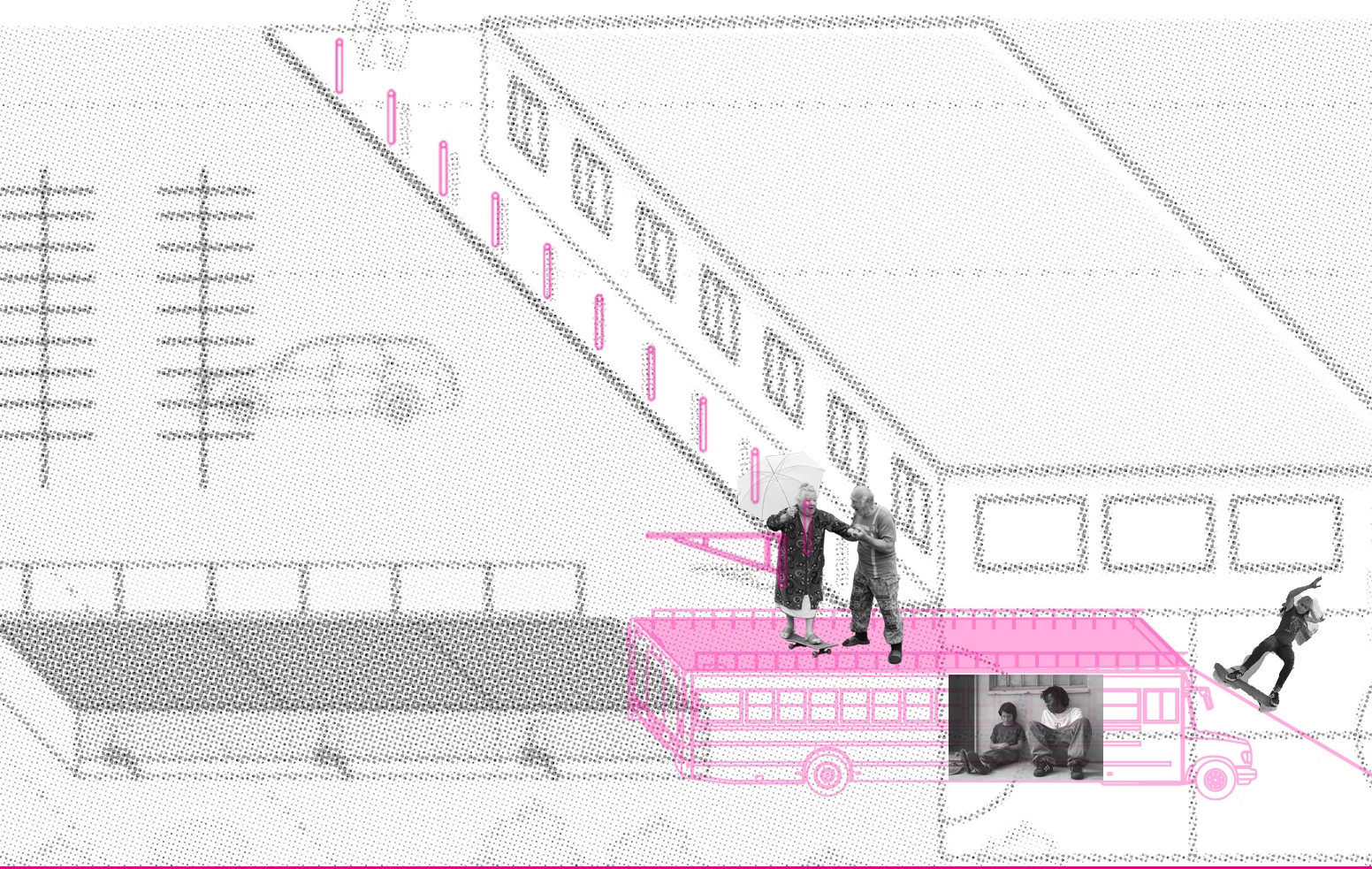

Kendra: So when I moved here, there was a whole bunch of farms and now there’s just a whole bunch of houses. So there’s not really much to do in my neighbourhood. There’s a Sobeys at the edge, and that’s about it. So boarding, It was, like, whenever I would go out it was never to go somewhere and do something. It was always strictly for me to like, relax and find my sense of peace. It’s your body directing you. You’re not thinking about it. You just have to go with it. It’s just different. I like it. When I was in a place where I couldn’t understand what was going on, and like, I was just trying to figure it out, I would get on my board. I have to face stuff when I get home or like when I get to school and stuff, and boarding really helps. I didn’t realize that that’s why I cling on to it so much.

What do you think it would be like if a skate park was brought to a mosque?

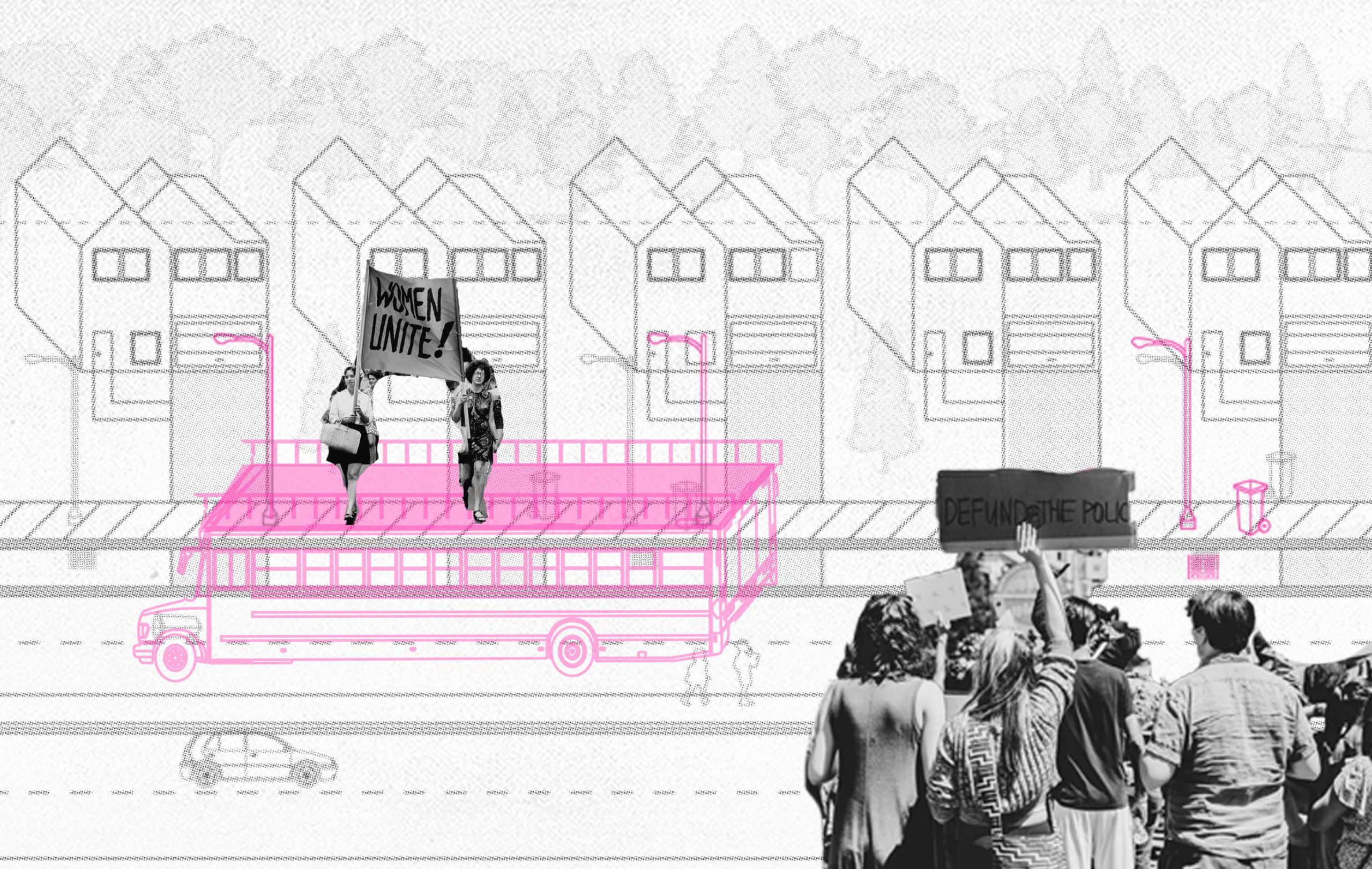

Amena: Having things like that would encourage more people to go. There’s this culture of a lot of older people who go to the mosque who judge the youth. There’s a lot of aspects of the mosque that deters younger people to go because you’re getting judged by a bunch of Auntie’s and stuff. You are pressured by your parents. Maybe if a skatepark was there, they would be happy to go. I just imagine, because our mosque has a very big brown community and also Somali, so I could just imagine a bunch of girls in their skirts skateboarding. Skater hijabis in there like crazy coloured, clothes, would look like a bunch of bosses.

What is your experience with at the skatepark?

Jenin: I don’t normally go to the skatepark but I want to. I want to get out of my comfort zone. Like not only because we’re woman, but because we’re women of color. So those spaces are kind of geared towards, like, not our demographic. So I understand that people are going to stare but I just gotta block them out and ignore them and just try to do my own thing.

How did you start skateboarding?

Zarina: I actually started skateboarding this year. And I think that a lot of people have been picking up skateboarding especially during COVID, who wouldnt have before. It is a very, white cis male thing. There’s this bubble that I wouldn’t normally feel comfortable or safe trying out. And boys are mean. You hear things like, if you can’t do an ollie on the first try you’re like you’re a fucking poser. And I’m like, really scared to do anything, like impact related or like getting hurt, and just looking stupid, honestly. So and I think after doing this for a few months, it definitely helped my confidence.

How would you describe your connection to skating?

Bhavika: When I skateboard, I just like free riding and mostly just chilling. I’m pretty decent, but just reminding myself that I could still call skateboarding something of my own, no matter what level I’m at, or no matter how basic my skills are. I did have a skateboard in high school. I lived for a long time in Brantford, it’s a really small suburb past Hamilton. My parents weren’t even okay with it. My mom made me hide my skateboard in the garage. She said “don’t let your dad see this. It will make you seem a hooligan or something!” I don’t know. The skateparks were not inclusive at all. And also, not to mention if you were non-white. It was only middle class white boys who’d like to skateboard. And if you weren’t, it was very inaccessible.

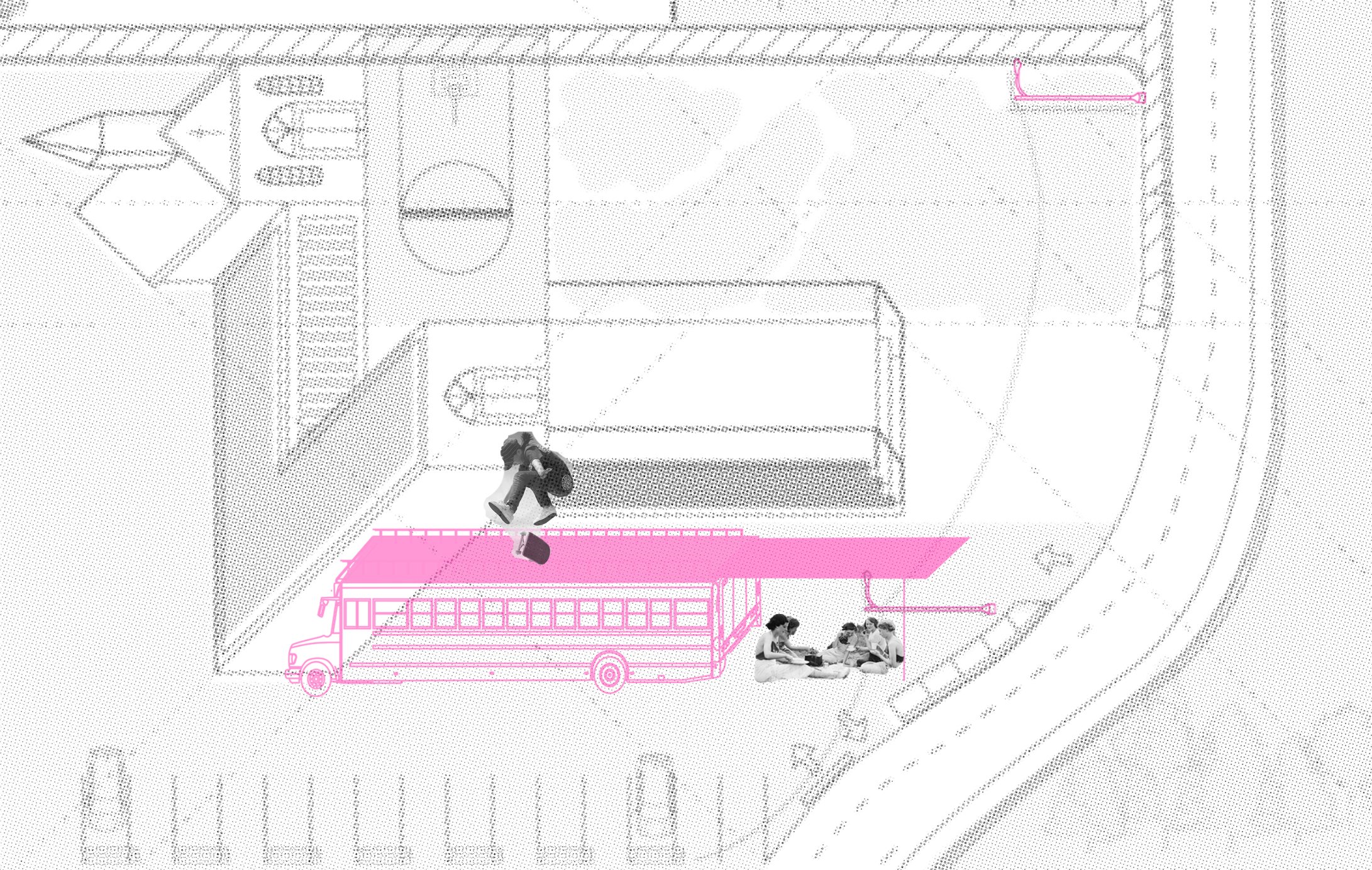

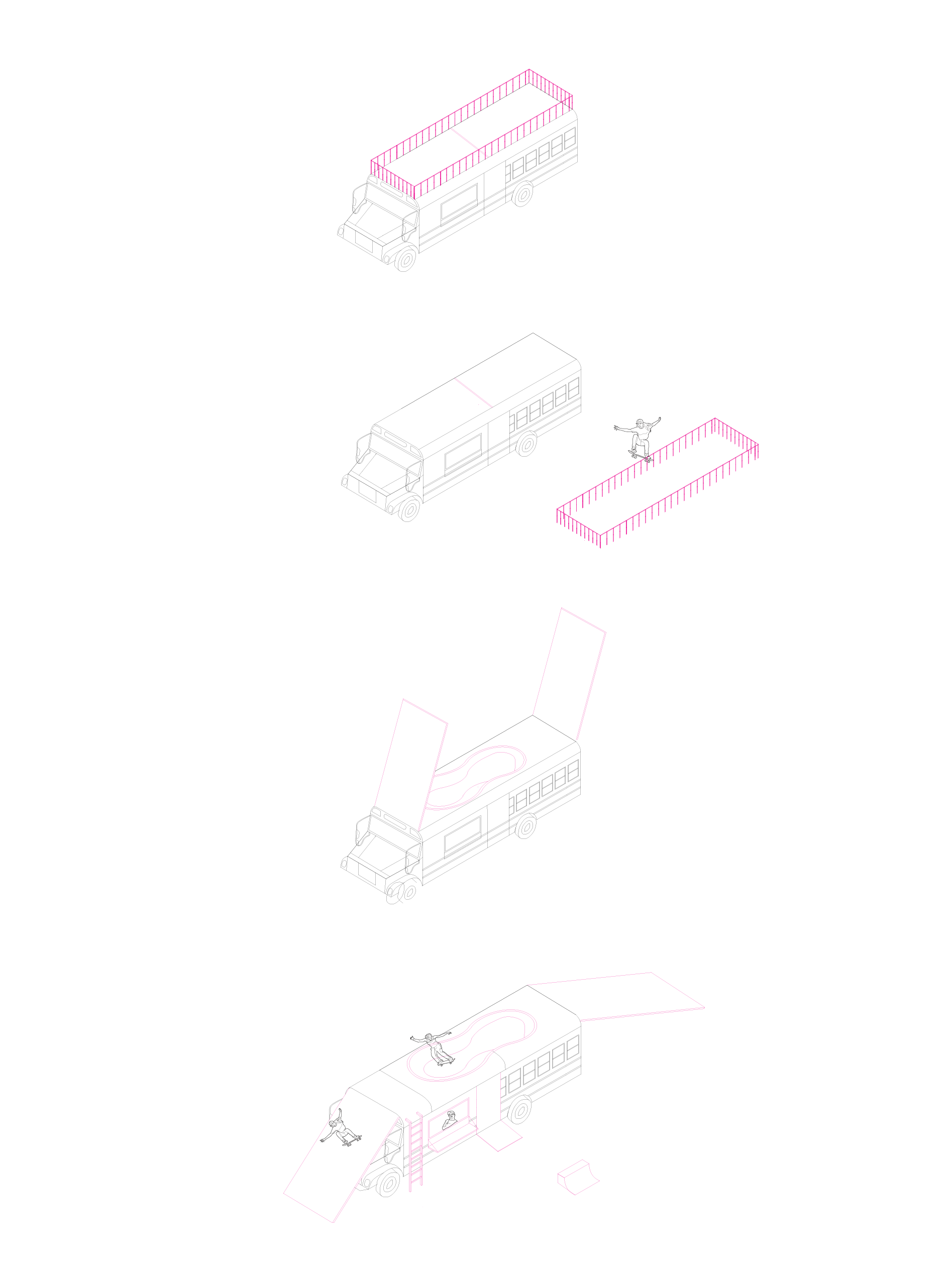

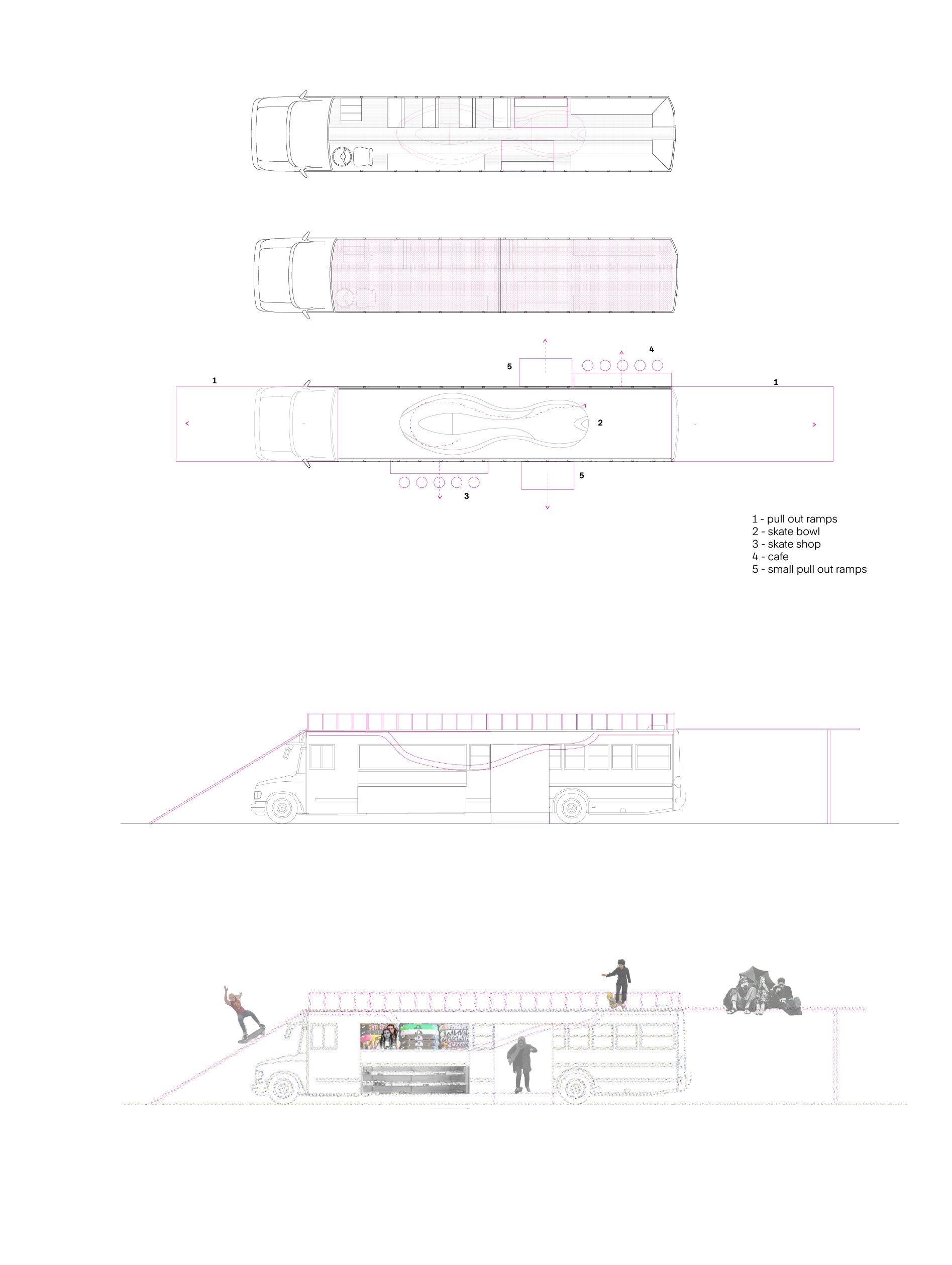

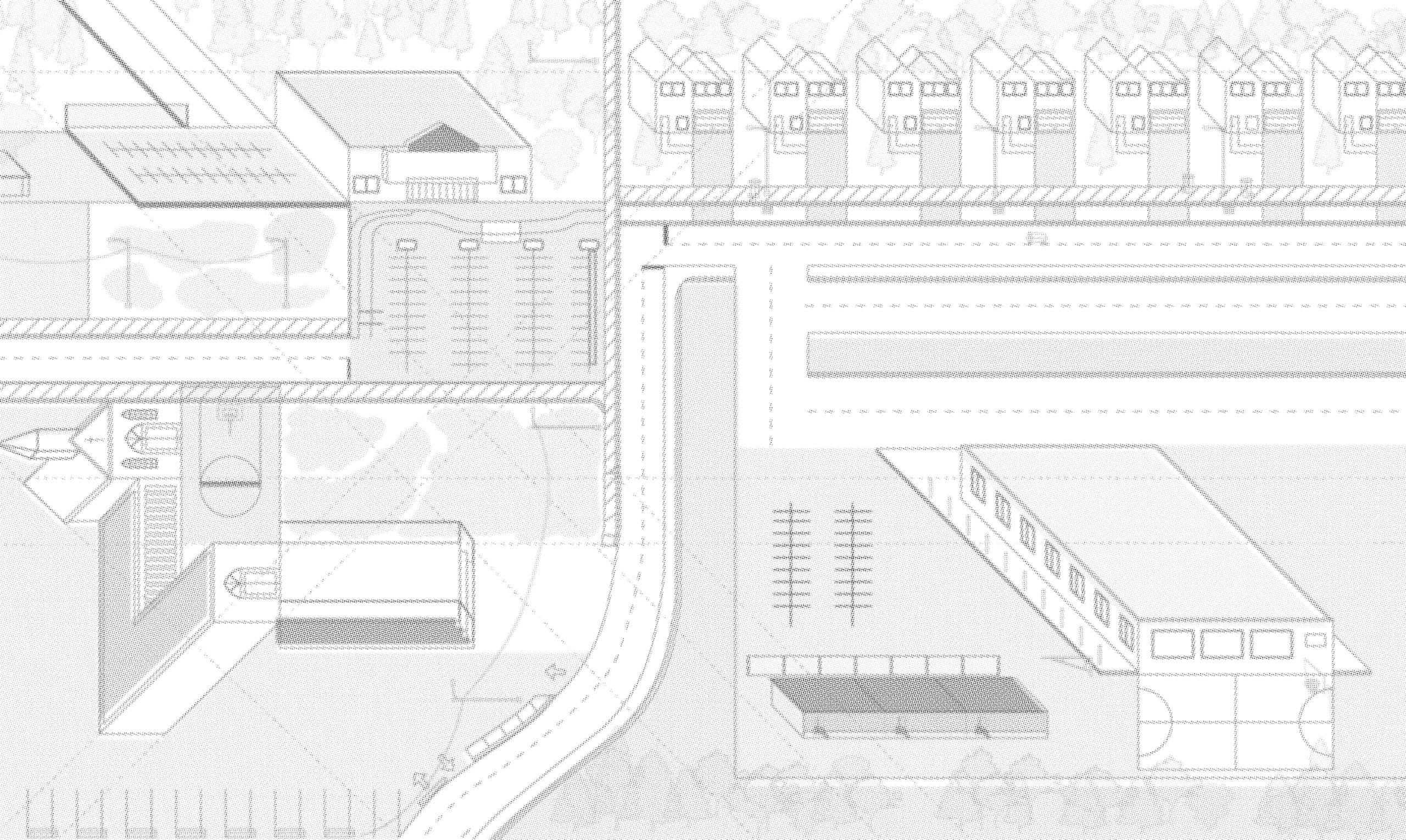

The vehicle I have designed is meant to occupy the unused spaces of suburban landscapes, such as empty parking lots or back alleyways. These spaces are often found around religious spaces, libraries, and strip malls. Through this investigation, an activated playscape has been designed to facilitate what skateboarding embodies: failing, trying new things, and building a community.