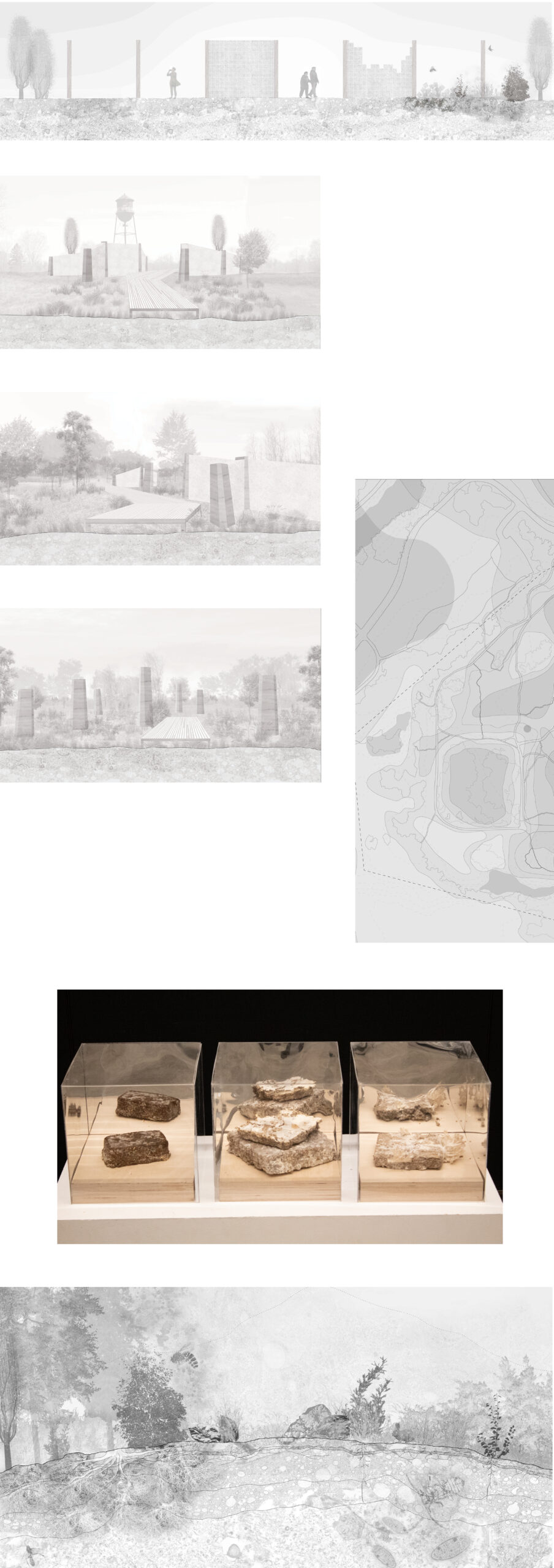

Architecture and built form play a key role in facilitating the relationship between humans and our natural environment. Too often, architecture is treated as a tool capable of separating human life from the metabolic processes of the natural world. Yet sites of human occupation are also sites of complex and entangled ecological processes which connect to a larger system of planetary ecology. The main protagonist in this thesis is mycorrhizal fungi or mycelium, the root systems of the fungal communities which produce mushrooms. Mycelium—the connective tissues of fungal networks—offers an opportunity to fundamentally challenge the misconception that architecture divides us from the natural world, both through acting as a major metabolic connector in landscapes, and due to its potential as a building material. Additionally, the architectural application of mycelium imposes an acknowledgement of how larger organic processes, such as decomposition, act upon architecture and urban landscapes, using the natural to challenge the ideological. Through processes of growth, engagement, and decomposition, these fungal structures suggest a new kind of relationship between architecture, site, and human inhabitation, implementing a kind of urban intervention that works within the entangled nature of landscapes, rather than against them.