Urban Genome Project Members Fernando A. Calderón-Figueroa, Daniel Silver, and Olimpia Bidian’s paper discussing Toronto’s Priority Area Program (2006–2013) has just been published in Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World. Here’s Fernando’s summary:

Among the multiple ways to subdivide a city, neighbourhoods are probably the most familiar to our everyday experience. It is not surprising that neighbourhoods have been at the centre of revitalization efforts for almost a century. Yet, the early 2000s marked a transition towards systematic efforts to define neighbourhoods and their boundaries and identify the most disadvantaged among them. We call this process the spatialization of social issues, which was largely facilitated by the proliferation of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology in both academic and policy circles. More importantly, planning decisions that emerged from this trend affected neighbourhoods’ trajectories over time beyond policymakers’ original intentions.

Our paper explores the unwanted consequences of spatializing social issues in three steps. First, we examine whether designating entire neighbourhoods for social policy may affect their desirability as expressed in changes in rent and housing prices and in new building permits. Second, we assess the extent to which designated neighbourhoods may leave out areas “in need” that fall outside their boundaries while including better-off families within them. Third, we analyze evidence on whether this spatially-targeted policies may expand the stigma associated with certain places—e.g., a “dangerous” intersection or a “poor” housing complex—to all the designated neighbourhoods and the people within them. We draw on difference-in-difference models and income distribution analysis for first two parts, and on a qualitative assessment of newspaper articles and policy documents for the third one.

We make a twofold intervention in the existing literature on place-based policies. First, we bring together two social policy debates that share the common goal of attempting to improve the quality of life of those in areas of concentrated disadvantage. The “targeted” versus “universal” debate, heir to the 1970s welfare state scholarship, addresses the effectiveness and drawbacks of each of these approaches. The second is the “individual” versus “place” debate, in which researchers assess whether urban revitalization efforts should focus on individuals or entire places (e.g., “enterprise zones”). We bring together these traditions by treating each approach—targeted, universal, individual, and place—as dimensions in a two-by-two table. This intervention allows us to identify the potential negative externalities of neighbourhoods as policy targets (the targeted-place approach) while uncovering the potential of less-explored possibilities beyond spatial designations (the universal-place approach). Our second intervention is to bring to the fore a sociological conception of the neighbourhood that highlights its singularities as a scale of policy intervention. We suggest that neighbourhoods are interwoven in the urban landscape—thus, treating them as isolated entities poses significant challenges—and that their reputations matter for people’s self-conceptions and decision-making processes.

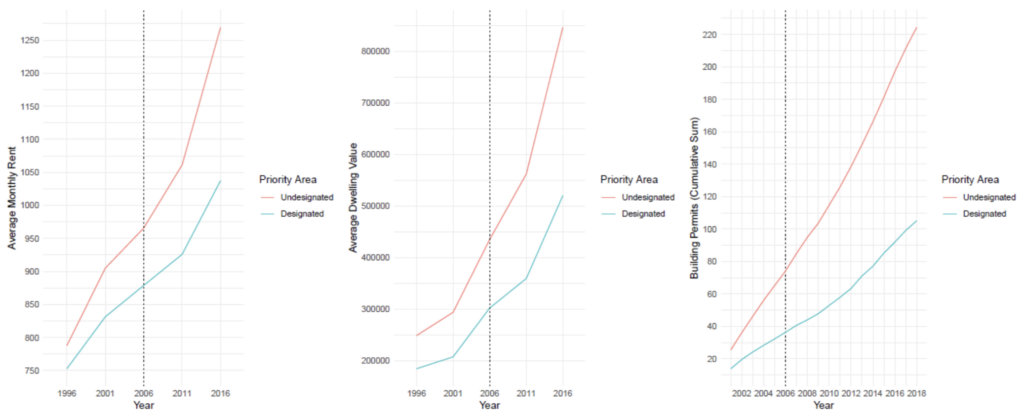

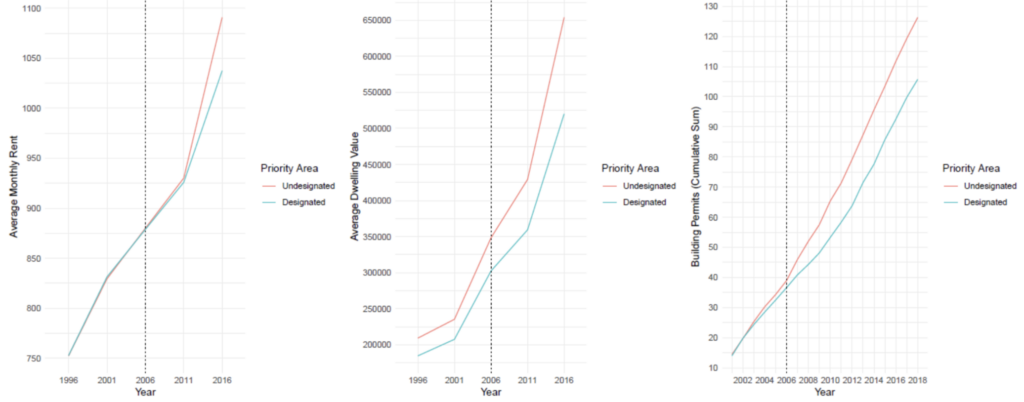

The study examines these ideas through the case of the Toronto Strong Neighbourhoods Strategy as it was implemented between 2006 and 2011. The program established 13 “priority areas for investment” and aimed to channel federal, provincial, and municipal resources into underserved communities to improve their social infrastructure. This was a response to the increasing poverty and crime rates in Toronto’s inner-suburban neighbourhoods. Previous research has found mixed evidence of the program’s effectiveness. However, we focus on assessing its unintended consequences, particularly regarding the lasting impact of the “priority neighbourhood” label as a shorthand for the target areas even after the program was relaunched in 2011. We find that, compared to otherwise similar and nearby places, those that received the “priority” designated had substantially lower growth in home prices, building permits, and rents.

(a)

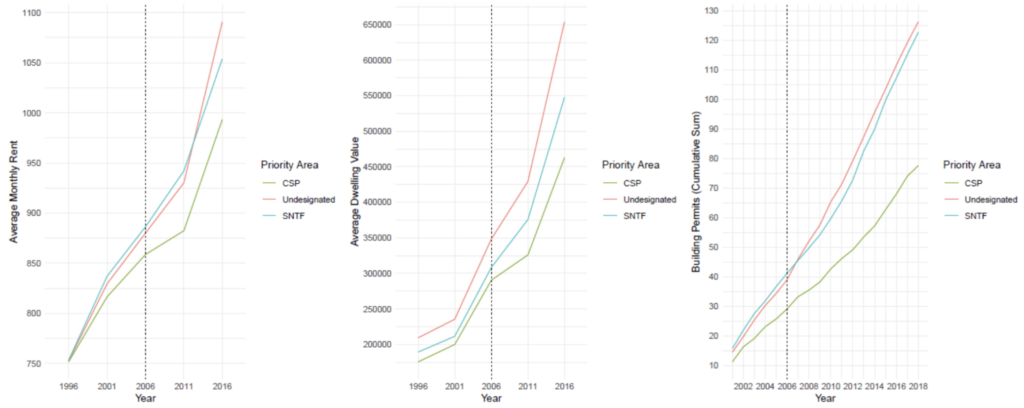

(b)

(c)

Figure 2. Graphs (a) and (b) show trajectories comparing undesignated (red) and designated (light blue) DA paths on average monthly rent (left), average dwelling value (centre), and the cumulative sum of building permits (right) before (a) and after (b) matching. In graph (a), the markedly different trajectories respond to comparing the priority areas with the rest of the city. Graph (b) shows narrower trajectories albeit the growing gap between undesignated and designated areas across the three outcomes remains. Finally, graph (c) splits the priority areas between neighbourhoods designated by the CSP (green) and those included by the SNTF (light blue). The plots in graph (c) show that the gap between undesignated and designated DA paths grows wider over time for the CSP priority areas. Each outcome (column) has a different scale.

The paper does not aim to entirely dismiss place-based policies but to expand how we think about them. Current location-based technology allows better ways to identify neighbourhoods and people’s needs for social infrastructure based on mobility and consumption patterns, street connectivity, among other measures, rather than relying on imposed official boundaries. Targeted policies may be combined with more universal approaches that reduce spatial inequalities while using resources efficiently. Our goal is to bring back sociological view of neighbourhoods as complex and interdependent foci of social life rather than isolated policy targets.

Listen to lead author Fernando A. Calderón-Figueroa discuss this paper by streaming the video below.