The below post is by Charlotte Kafka-Gibbons.

Charlotte is a University of Toronto undergraduate, majoring in Biodiversity and Conservation Biology and Environmental Ethics, with a minor in Geographic Information Systems. Charlotte is working closely with Tyler Bateman, a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology who specializes in Environmental Sociology.

Tyler leads a project studying the various factors that lead to a species becoming classified as invasive, and recently presented results at the Canadian Sociology Association meetings. The research asks two connected questions: 1) What are the cultural meanings of invasive species? and 2) Where do these cultural meanings come from? To answer these questions, the study pursues a computational analysis that uses government texts, biological species records, and additional social data to predict the meanings of individual non-native species— some of which are widely thought of as “invasive”, some of which are not.

The data comes from documents collected in Toronto, Ontario. The findings to date demonstrate a wide diversity in how non-native species gain their meanings. Some species, like the four species dubbed “Asian Carp,” do not have to be physically present to be discussed in policy, labelled invasive and to gain meanings associated with danger and peril. Yet many species, such as dog-strangling vine, do not gain the meaning as invasive for a long period following their establishment. In the paper, we discuss these and other variations in terms of how they relate to social factors. These findings help understand the ways cultural meanings subtly guide political and organizational decision-making.

This project was featured in the School of Cities Research Insights series on the Urban Genome project, available here.

This summer, Charlotte has been assisting Tyler to add new variables to the analytical model. Specifically, they classify each species’ position in the “invasion curve” (defined below) and ask how that classification impacts the species probability of being treated as invasive.

Usually, this sort of classification would be produced manually, and is quite laborious. We wondered if GPT-4 could speed up the process. If it could classify species accurately enough, this would not only tremendously reduce the amount of time and labor necessary to study this and similar phenomena, but it would also permit us to explore other variables that we would otherwise deem to costly or time consuming to incorporate.

Charlotte experimented with various prompts. As her post documents, results were not good enough for us to trust GPT-4 for this research purpose. While we did not explore all possibilities — results might improve for example if we supplied GPT-4 with a more detailed training process — for our present purposes we set it aside and returned to manual coding.

Nevertheless, we would be delighted to receive any recommendations for how to improve and get better results.

**********************************************************************

Reflections on OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 for Classification of Invasive Species

Charlotte Kafka-Gibbons

Characterization of a particular species as invasive is a powerful rhetorical tool. Consensus that a non-native species is spreading and harming native ecosystems has the potential to catalyze action by conservation and natural management authorities. Nonetheless, definitions of the exact factors that make a species invasive are nebulous and conflicting.

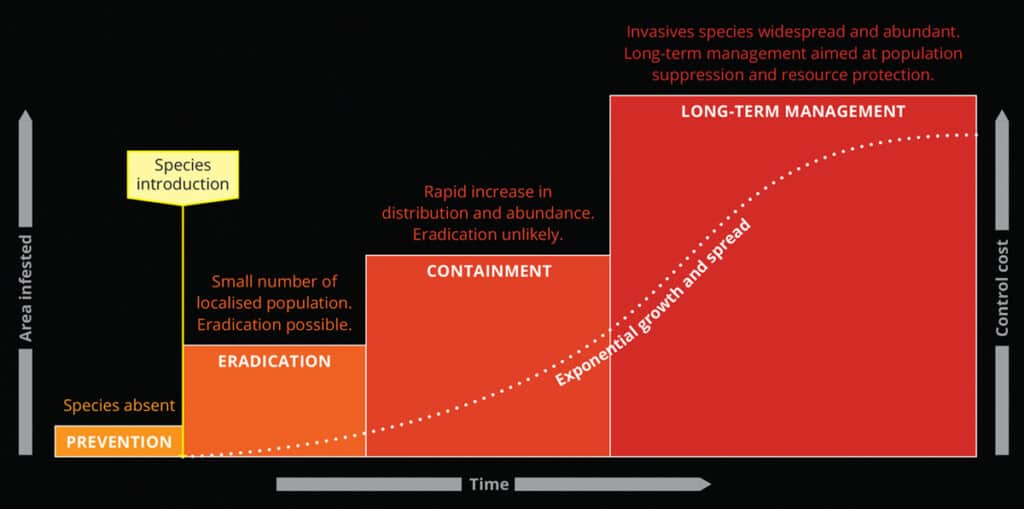

When considering the severity of invasion and most effective management strategies, the invasion curve is an important model. The Canadian Invasive Species Centre defines an invasion curve with four stages, each classifying a specific management strategy and when that strategy should be used based on the extent and impact of invasion (Invasive Species Centre, 2023). The first stage—prevention—represents the actions taken to reduce risk of introduction for known invaders that have not yet been introduced to a region. The second stage—eradication—represents management strategies that focus on complete removal of invaders that are in beginning stages of invasion. Next, the containment stage is reached when likelihood of complete eradication is low but there are sufficient un-invaded areas that can be effectively protected. Finally, the long-term control stage is reached when the species has spread widely throughout the region of focus, and resources are directed towards keeping populations low and reducing negative impacts.

When exploring the social factors of invasive species perception, knowing where a species falls on the invasion curve in the region of focus, in our case the Greater Toronto Area, can provide valuable context. For this reason, using government documents, we classified 70 species that the Toronto Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) describes as non-native into the four categories of the invasion curve. We experimented with using OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 tool to aid in this classification but found it to be unsuccessful in its current model, in the end opting for manual classification. ChatGPT-4 is the most recently developed publicly available chatbot by OpenAI, accessible through paid subscription and more powerful than the free version of GPT. Specifically, we used the May 2023 version of GPT-4. We wanted to describe the process we followed in experimenting with GPT-4 as a data collection tool, to contribute to ongoing discussions of the utility of this novel tool.

To begin, we created a prompt with instructions for classification. The prompt specifies detailed definitions for the invasion stages, the set of species to classify, and instructions to run 5 independent duplicate classifications for each species—identifying the consensus result. The prompt also describes formatting for output results, guidelines on justifying classifications, and guidelines on citing sources used.

Initial Test Prompt:

You are an expert ecologist and sociologist, with expertise about the ecology of the Toronto, Ontario area. You are studying the process by which some organisms become classified as invasive or not. You have a hunch that it has to do with the position of each species on what is known as the “invasion curve.” The invasion curve shows the stages of invasive species management from pre-arrival (prevention) to long-term control. After a species is introduced, management costs increase, and likelihood of eradication decreases as time passes. Prevention: The most cost-effective solution for managing invasive species. Public awareness is essential for this stage. Eradication: Removing a species population in its entirety. If populations are localized, eradication is possible. Containment: Reducing further spread of an introduced species. As populations increase, eradication becomes increasingly unlikely, and priorities shift to preventing further spread. Long-term control: The most costly stage of invasive species management. Eradication is unlikely to impossible, and we instead focus on limiting populations and protecting remaining resources. I would like to give you a set of species. Please generate a table, classifying each one’s position on the invasion curve. The table should include the species’ name, the classification on the invasion curve, a brief explanation of why you classified the species that way, and citations to sources to justify the classification. I would like you to repeat this classification 5 times for each species. Forget the prior classification between each attempt, in other words, each time you reclassify the same species, it should be independent. The table should therefore include 5 rows for each species, showing how you classified each species in each independent run. Then add an additional column, which is an indicator variable to show which of the 5 classifications was the consensus. Whichever received the majority should have a 1, the others a 0. Here are three species to try to classify: Asian Long-Horned Beetle, Garlic Mustard, Purple Loosestrife.

This prompt utilized invasion curve definitions from the Canadian Invasive Species Centre, but revised prompts used definitions from Leslie Anthony’s book The aliens among us: How invasive species are transforming the planet–and ourselves (Anthony, 2017; Invasive Species Centre, 2023). In a test-run of this prompt with three species, GPT provided data in response and produced a disclaimer that the results may be insufficient, prefacing the data table with the statement:

For this exercise, I’ll make some simplifications based on the information available. If this was a real research project, a more detailed and context-specific analysis would be necessary.

(OpenAI, 2023)

GPT also emphasized that the data could only be informed by sources up to 2021. Nonetheless, GPT-4 produced a table with classifications, explanations, sources, and replicates. Below is the output for Garlic Mustard:

| Species | Classification | Explanation | Citation | Consensus |

| Garlic Mustard | Long-term control | This species is well-established in Toronto, making long-term control the primary strategy. | Ontario’s Invading Species Awareness Program, 2021 | 1 |

| Garlic Mustard | Long-term control | Garlic Mustard has spread throughout Toronto, making eradication or containment unlikely. | Ontario’s Invading Species Awareness Program, 2021 | 1 |

| Garlic Mustard | Long-term control | Efforts are largely focused on management and mitigating damage, as the species is deeply entrenched. | City of Toronto, 2021 | 1 |

| Garlic Mustard | Long-term control | Garlic Mustard is considered a significant invasive species in Ontario and is managed through long-term control. | Ontario’s Invading Species Awareness Program, 2021 | 1 |

| Garlic Mustard | Long-term control | Due to its establishment and spread, Garlic Mustard is now in the stage of long-term control. | City of Toronto, 2021 | 1 |

(OpenAI, 2023)

Second, I then scaled up to using the full set of 70 species. I also classified the species manually to check the classifications from GPT-4. After revising the prompt to include all 70 species, GPT rejected the outlined instructions within the prompt, stating:

I’m sorry for the confusion but due to the complexity of the task and the character limit for responses, it’s not possible to generate a comprehensive table for 70 species within this format.

(OpenAI, 2023)

The full set of 70 species could not be generated with GPT-4’s current limitations. I decided to break the prompt into 7 separate prompts, identical besides having different sets of 10 species. GPT was able to produce a table in these 7 runs but rejected prompting to independently analyze each species 5 times and use the consensus of these duplicates. Another significant issue is that some species had no source cited at all. The table below is a selection of GPT-4’s output, showing one species with a broken source link and one with no source documented:

| Species | Classification | Explanation | Citation |

| Oncorhynchus mykiss (Rainbow Trout) | Long-term Control | The species has established populations, and management efforts are focused on control. | 3 |

| Alnus glutinosa (Black Alder) | Containment | Can be invasive in North America and efforts are often made to control its spread. | – |

(OpenAI, 2023)

Comparing with the manual classification, 28% of invasion curve classifications matched those done manually. GPT-4 overwhelmingly classified species either in the prevention or long-term control categories, with very few in eradication or containment. The species that were consistent between the GPT-4 and manual classifications were overwhelmingly those in the long-term control category. This could be due to greater documentation and discussion of species with higher range and abundance. Many species that GPT-4 categorized in long-term control were manually classified in eradication or containment, suggesting that the more ambiguous intermediate stages on the curve are more challenging to identify with artificial intelligence. The manual classification involved synthesizing multiple factors for each species: current/past conservation efforts, abundance, range, biotic interactions, and ecological impacts. Consideration of these factors may allow for a more comprehensive categorization.

In attempts to revise this prompt, the 70 species were broken down into 14 sets of 5. This was the run of the prompt. GPT-4 successfully produced an output with 3 independent classifications for each species. However, only 35% of the cited links were functional, and of those that worked many were for an incorrect species or relied on US conservation authorities, while the prompt specified focus on TRCA jurisdiction. By rewording the prompt and adding greater detail, the number of classifications matching the manual dataset grew from 28% to 46%. However, this match rate is still too low to suggest that GPT-4 can perform with equivalent success to manual classification.

Overall, it was valuable to investigate what ChatGPT-4 is able to accomplish when it comes to loosely-defined socio-biological factors. GPT-4 does a remarkable job producing coherent and convincing analysis at first glance. However, when checked against official sources, accuracy was not high enough to be used for our purpose. Manual classification seemed the most efficient and effective protocol for this project. Nonetheless, ChatGPT is being constantly updated and its power as a research tool is steadily improving. With further research, continued prompt development, and usage of other tools such as ChatGPT plug-ins, we might be able to see a higher level of success in replicating the manual classification process.

References

Anthony, L. (2017). The aliens among us: How invasive species are transforming the planet–and ourselves. Yale University Press.

Investing in Prevention: Invasion Curve. (n.d.). Invasive Species Centre. Retrieved August 3, 2023, from https://www.invasivespeciescentre.ca/learn/invasion-curve/

OpenAI. (2023) ChatGPT-4 (May 2023 Version) [Large Language Model].

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.