Evaluative comments, also known as reviews, are crucial for the sharing economy systems, such as Airbnb, and Couchsurfing. We reveal by studying reviews in different systems of the hosting segment that there is a considerable imbalance towards more positive reviews in the sharing economy systems. We discuss possible implications for this fact, with the help of an experiment performed with volunteers. We also discuss how to explore the results obtained to develop new mechanisms to help users’ decision-making.

Sharing economy is a term that represents person-to-person activities to obtain, provide, or share access to goods and services, coordinated by online services based on a community of users [See The Sharing Economy].

For example, in the hosting segment, Airbnb is a service that connects people who have a space to share with people who are looking for a place to stay, and the host stipulates the value of hosting. Couchsurfing allows people to share their areas similar to Airbnb; however, the hosts do not charge for the service provided. These services usually compete with hotels, being representatives of the traditional economy. Booking.com is one of the most famous platforms in this category.

Users on the sharing economy platforms are typically invited to express their opinions about the service being used, and reviews are among the most critical types. These opinions are crucial to many platforms in this segment. It is not uncommon for businesses like Uber, another example in the transportation segment, to require drivers to have a particular feedback rating to be kept in the system. In the hosting context, negative reviews about hosts can impact rental decision-making.

An essential element of several businesses of the sharing economy, including hosting services, is the personal contact between the guest and the host. This personal contact, intense or less intense, may favor creating a relationship between guest and host. The same situation is not common in hosting services of the traditional economy. We believe this personal contact may put guests in a difficult spot to provide a negative review in services of the sharing economy. Of course, other factors might also play a role in excessively positive reviews. For example, the bidirectional rating systems, i.e., hosts rate guests, and vice-versa, which are common mechanisms in the sharing economy systems and not so common in systems of the traditional economy. Independently of the reason, if this phenomenon tends to happen more on services of the sharing economy, it could undermine an adequate assessment of the service consumed.

With that in mind, we focused on answering a fundamental question: Do reviews in hosting services tend to be less negative in the sharing economy?

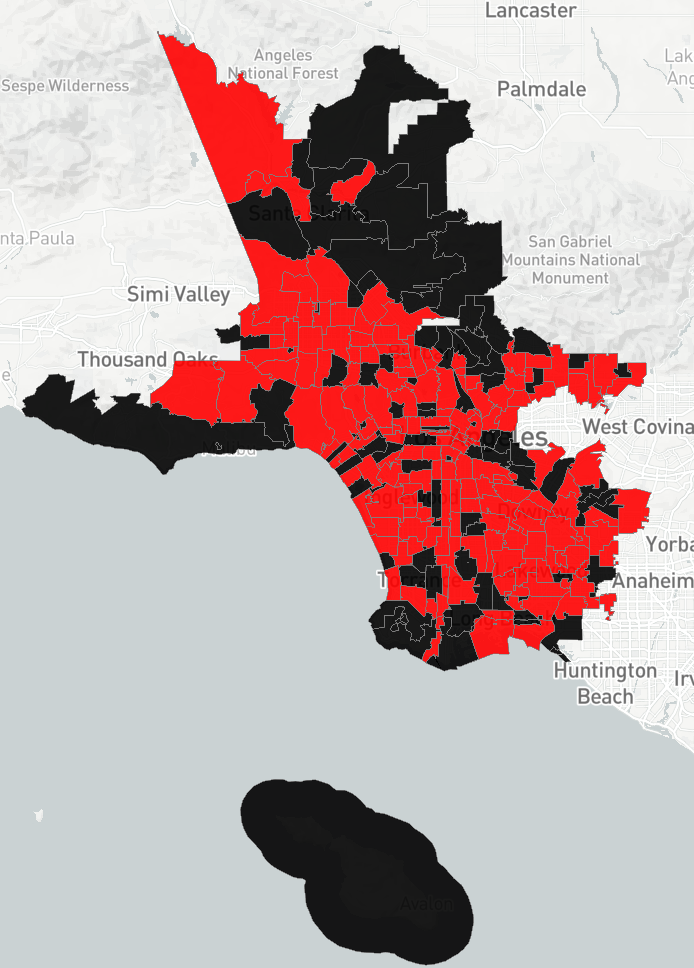

To conduct this study, we collected reviews from two sharing economy platforms, Airbnb and Couchsurfing, and a representative of the traditional economy, Booking.com. We consider accommodations offered in three Brazilian cities and three cities in the United States. After getting these data, we performed sentiment analysis on the shared texts. We found that reviews in the sharing economy tend to be more positive than those in the traditional economy. This result is illustrated in the figure below, which shows the distribution of sentiments for all platforms, considering all cities studied separately. Note that this result is consistent for all cities. For more information about all technical details, please refer to the original paper that this post is based on (see it here).

We also present some key features of these comments and made several supplementary analyses (all presented here), reinforcing the insights observed. For example, we investigate the topics most addressed by users in negative comments. We focus on negative comments because we hypothesize that, in addition to rarer, they tend not to be very informative on hosting platforms of sharing economy. We identified ten topics for negative reviews on Airbnb and Booking. The table below presents ten words that best describe each topic. We note that all topics for Booking tend to be negative. For example, Topic 2 is related to complaints regarding the room, and Topic 4 is more related to the staff. However, when analyzing the topics for Airbnb, we can identify several topics that suggest positive mentions, all marked in bold and with “**” in the table. For example, Topic 4 suggests being related to the accommodation in general, where the topic indicates that users have approved the stay. For reviews in Portuguese, the patterns are very similar. This means that despite the final negative score of some comments (potentially less intense), they have positive mentions in the evaluation.

This phenomenon of more positive reviews on the sharing economy systems may limit users’ perception of the quality of a particular accomofation. As negative evaluations tend to be more scarce in reviews in the sharing economy, neutral opinions can become more critical. It is as if the polarity scale began near the neutral, representing the most negative opinions expressed by the users. This suggests that neutral evaluations should be taken into account at the time of choosing accommodation. These evaluations might make a difference in classification and decision making when selecting a place to stay.

To better understand our results’ implications, we performed a study with volunteers to evaluate how the observed phenomenon affects the user decision-making process. After that, we found evidence that the classification of establishments at Airbnb made by users could be affected due to the lack of negative evaluations.

Our findings suggest that reviews on different platforms might require different interpretations, especially for algorithmic-based decision-making approaches that use reviews in the learning phase. In this regard, our study still discusses how to explore the results to choose better accommodations in the sharing economy. We show how the proposition of simple new metrics that consider the reviews’ sentiment could help to minimize problems that can emerge from the uncovered phenomenon.

We hope our quantitative analysis and observations inspire new approaches to account for this perceived bias towards positivity in hosting platforms.

For more details, see our full paper, “Neutrality May Matter: Sentiment Analysis in Reviews of Airbnb, Booking, and Couchsurfing in Brazil and USA“.