What place is there for public spiritedness in the metropolis? Here, public spiritedness is broadly defined as a sense of obligation to others, which is presupposed by a sense of community. This definition considers the humanity of others, even if they are strangers. It suggests that there is a spirit, a personal philosophy, that is rooted in the desire to consider the welfare of not just the self, but of others too. Public spiritedness in this sense is most conducive to desirable outcomes in a society when it is practised by the masses. Otherwise, the incentive to care for others when others do not care for you diminishes. There is no pleasure in being a victim amidst a collective action problem: no one wants to be in an unfair position of supporting a “free-rider”. As such, public-spiritedness is a way of life that is practised by the self, but yields maximal benefit and becomes most compelling when it is practiced by a collective.

The anonymized nature of being in a city makes the practice of public-spiritedness more difficult than in a smaller community—like one typical of a rural area. In a city with millions of people, it becomes more difficult to consider the humanity of others due to the impossibility of meaningfully engaging with a sizeable fraction of a city’s residents. This lack of engagement not merely inhibits one’s ability to consider the humanity of the other when most of the others are unknown. It also inhibits one’s ability to gauge the level of public-spiritedness practiced by others in the city. As such, it may seem that the rational position is to act selfishly without regard for other community members.

Given the desirability of public-spiritedness, what place does it occupy in a city? Surely, there ought to be physical venues in which acts stemming from public-spiritedness can be displayed. Displays of this sort are prime examples of “signals” in the Toronto Urban Evolution Model: they transmit ideas about how to properly organize urban life. Signals can include formal material such as policy documents but they also include the everyday ways in which urbanities communicate to one another the models of urban life they value. Accordingly, some physical venues may signal the practice of selflessness to deter suspicions relating to collective action issues, but also emphasize the goodness of a city’s inhabitants. But the practice of public-spiritedness is also a private one that manifests in situations away from the public eye. To be conscientious of the humanity of the other requires an internalized understanding of how neighbours, no matter how near or how far, are people, too. They may be someone’s mother or someone’s brother. They have basic needs like access to food and water, but also personal needs like dignity and love.

This essay will focus on the porch as physical places for cultivating public- spiritedness and a key site for the evolution of “formemes.” It does not suggest the decline of the porch coincides with the loss of a sense of public-spiritedness, as Richard H. Thomas suggests in his “From Porch to Patio.” This essay is a celebration of the porch as an historically significant space for public gathering, both intentional and accidental.

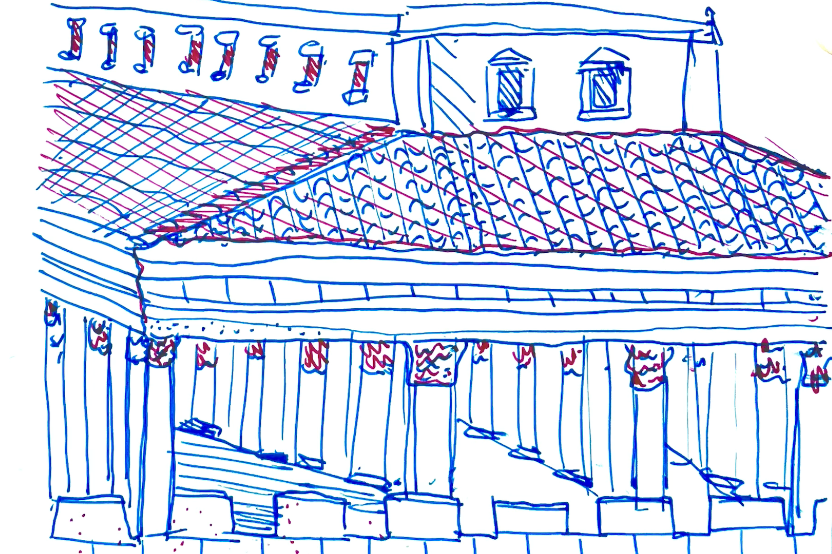

Porches have evolved over millennia to reflect architectural waves and cultural contexts. Porches predate the bible, in which they may be referred to as “covered ways,” “porticoes” and “colonnades.” The porch, in the biblical context, more closely resembles the agoras (open place of assembly) observed in Greek documents like Plato’s Republic. By this, I mean the porch is a place at which individuals congregate intentionally, rather than on a whim as one might in the case of a neighbor’s porch in the context of a modern American suburb. In Acts 5:12 (Common English Bible), “The apostles performed many signs and wonders among the people. They would come together regularly at Solomon’s Porch.” This porch is not a small enclosure by a home’s entry way. This religious place of prayer and miracle is more fittingly built as a long pillared walkway running the entire eastern side of the Temple’s Outer Court in Jerusalem. As Solomon’s Porch, along with the rest of Herod’s temple, was destroyed by the Romans in A.D. 70, modern-day understanding of porch’s purpose and appearance largely relies on its observations in the Bible.

The porch has lived on as a symbol for congregation vital to the health of communities. TADAMUN Initiative declares “public libraries, community centers, public schools and places of worship […] [as] the “front porches” of civil society” in their declaration for the need of public spaces “accessible to all citizens, regardless of race, age, gender, income, or religion”. Here, the porch is a space not exclusive to any religious population: it is an open and public space to achieve the goods necessary for a community’s standards of a good life (e.g. access to education, social connection, freedom to worship).

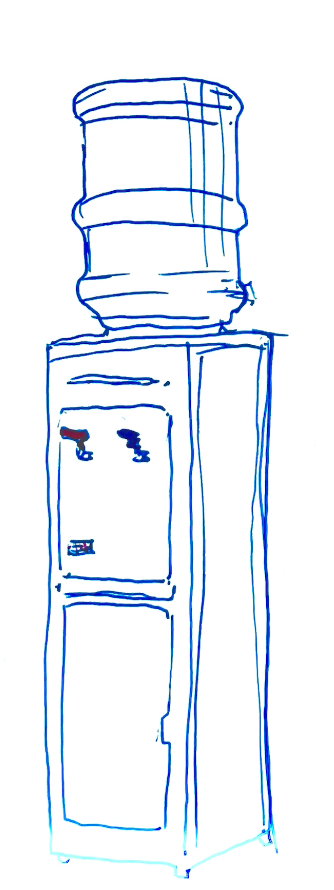

Robert Putnam, when referring to social capital in “Bowling Alone,” also mentions the role of the porch in a healthy community. He observes “porch stoops” as places for “the community ‘mothers’ [to serve] as the neighborhood’s eyes and ears”. He admires the Rosteans, the inhabitants of Roseto, a modest village nestled in Eastern Pennsylvania, for their abundant social capital: “By day they congregated on front porches to watch the comings and goings, and by night they gravitated to local social clubs. In the 1960s the researchers began to suspect that social capital (though they didn’t use the term) was the key to Rosetans’ healthy hearts.” In this context, the porch is a necessary venue for companionship and support during the day. In his research on the decline of social capital, Putnam observes the rise of vocational communities amidst the decline of locational communities (like the Rosteans’). In writing, “perhaps we have simply transferred more of our friendships, more of our civic discussions, and more of our community ties from the front porch to the water cooler,” Putnam suggests the function of the porch has been transferred from home-based to work-based spaces.

Like Putnam, Richard H. Thomas identifies the necessity of deliberation among community members and likewise the importance of spaces to host such deliberation. In his “From Porch to Patio,” he laments the fall of the front-facing porch amidst the rise of the private, enclosed back patio. Whereas the sense of community that “often characterized the nineteenth-century village resulted from the forms of social interaction that the porch facilitated,” the “twentieth century man has achieved the sense of privacy in his patio [in exchange for] part of his public nature” (126-127). The back facing patio, irrespective of whether it is enclosed or not, is by nature private from the public eye. As such, its occupation by inhabitants however social or its decoration by landscaping however intricate, would not invite impromptu deliberations or even mere interactions from passersby. The back patio is engineered to deter the cultivation of public- spiritedness, it is a refuge from the public in attempt to maintain privacy. The porch, by contrast, is an accidental venue for inviting nods of approval from passengers of carriages (121), impromptu deliberations by neighbours (compared to pre-planned neighbourhood coffees and bridge parties) (122), and quick greetings (122). These are all social interactions necessary in maintaining public-spiritedness. A love of the neighbor (referred to as ‘agape’ in the Bible), or the mere reminder of the humanity of the other requires the lived experience of social interaction. The porch has survived throughout millennia as a place for such interaction, and by extension: as the physical venue for cultivating public-spiritedness.

Encouragingly, Urban Genome Project member Khalil Martin’s research finds that the number of porches has dramatically increased in the past twenty five years. This disputes Richard H. Thomas’s theory of the porch’s decline amidst growing interest in back patios. Martin has found, using data from the U.S. Survey of Construction, that the proportion of American single-family homes that include a porch has increased from around 50% in 2000 to 64% in 2020. Furthermore, owner-built and contractor-built homes were consistently more likely to include a porch than homes built for sale or rent. This seems to indicate that people generally choose to have a porch when they can.

Martin’s research finds that the porch continues to be recognized in North America to be an important social infrastructure and has gained status as “an icon for community and civic mindedness, through the spontaneous and liminal interactions it affords.”

The American front porch has been used for a space for social rituals and ceremonies, such as summer tea rituals, courtship rituals, and seasonal events. Previously, American front porch has been used as a stage for performance and self-presentation, such as the various “porch campaigns” in early American politics, “porch concerts” (which also popularized during the pandemic), and even for social movements–for example when MLK preached on front porches. To add, the American front porch has also been used as a cultural signifier. Consider the adoption of Neo-classical porch styles by many statesmen, the mounting of national flags of porch posts, and other various style trends.

KHALIL MARTIN

His research hopes to show how people have adopted, and adapted, threshold forms to meet their contexts and create collective identity. A further step is to also explore how the diversity and dynamism of threshold form features and uses relate to the notion of community thriving. Khalil frames his work as a means to “understand the opportunities for spatial agency and participation, in the urban context”

As a side note, Martin notes there may have been a decline in porch adoption between 1945 and 1995, but that data his research focused on ranged between 2000 and 2020.

Although the strength or spread of public spiritedness is difficult to measure, it should be encouraged on the basis of cultivating moral respect. I argue that greater consideration paid to the humanity of the other will bolster a sense of obligation to others, and consequently reduce partisanship and alienation common of large heterogeneous cities. Further thought should be devoted to porch-like spaces in public, vocational, and private spaces in the interest of supporting a good life for members of locational and vocational communities alike.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.